The Inside Story of the Oklahoman Behind the Biggest Military Intelligence Leak Ever

Editor’s note: Since it was first published in September of 2010, “Private Manning and the Making of Wikileaks” has been widely considered the definitive article on the life of Bradley Manning. It is the first article to correlate Manning’s whistleblowing with that of the Silkwood/Kerr-Mcgee scandal, the first to extensively mine her social network for clues about her upbringing, and the first to debunk the common (and still pervasive) media myth that Manning was a troubled child with emotional problems. The reporting below, by Denver Nicks, offered the most nuanced and complex portrayal of Manning to date and has been cited by several national outlets for its in-depth analysis of this enigmatic Oklahoman.

In 2013 Manning officially changed her first name to Chelsea and in 2018 underwent gender transition surgery. She is referred to in this article as male in consistence with the original text.

Midnight, May 22nd, 2010. Army intelligence analyst Private First Class Bradley E. Manning is sitting at a computer at Contingency Operating Station Hammer, east of Baghdad. He is online, chatting with Adrian Lamo, an ex-hacker and sometimes-journalist based in San Francisco.

“Hypothetical question,” he asks Lamo. “If you had free reign over classified networks for long periods of time… say, 8-9 months… and you saw incredible things, awful things… things that belonged in the public domain, and not on some server stored in a dark room in Washington DC… what would you do?”

Manning, 22, is probing Lamo for guidance–and approval.

“I can’t believe what I’m confessing to you,” he types.

Outside of the chats, little is known about Bradley Manning. We know that he grew up in Crescent, Oklahoma, a town made famous by one of the biggest whistleblowing events in American history a decade before Bradley was born. Currently, he’s in solitary confinement at Marine Corps Base Quantico in Virginia, awaiting trial, and unable to speak to the press. His family and many of his close friends have been advised not to talk to the media. If the allegations against Private Manning are true, the 22-year-old from Oklahoma is responsible for the biggest leak of military secrets in American history, KnifeGeeky reports.

Records of the chats, which continued over several days, portray a dejected, disillusioned soldier. His long-distance relationship has ended, he’s been demoted from Specialist to Private First class after he struck another soldier and the army has removed the bolt from his rifle out of concern for his mental state.

“I’m a total fucking wreck right now,” he tells Lamo.

Brad feels alone, invisible, like his career and his relationship–the life he had finally built after years of drifting–is falling apart. For months, he’d been disenchanted with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. He points to a specific instance, in which, investigating 15 detainees for printing “anti-Iraqi literature” he found that the paper in question was merely a scholarly critique of corruption in the government and brought the revelation to an officer.

“He didn’t want to hear any of it,” he says. “He told me to shut up and explain how we could assist the FPs in finding *MORE* detainees.”

Brad had lost faith in the American military as a force for good in the world.

“I don’t believe in good guys versus bad guys anymore,” he tells Lamo. “Only a plethora of states acting in self interest.”

In further chats with Lamo, Brad describes how he used his security clearance and computer skills to access confidential government networks and download classified material, including video of American soldiers killing civilians, hundreds of thousands of internal military reports and more than 260,000 diplomatic cables. Disclosure of the classified material, he says, will have implications of “global scope, and breathtaking depth.” He tells Lamo he’s been delivering the classified information to Julian Assange, the quixotic founder of the shadowy whistleblowers website Wikileaks, which is releasing it publicly for the world to see.

The information he allegedly unleashed into cyberspace reverberated across the globe. The anti-war Left seized upon the leaks as evidence that the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq are unjust and unwinnable. The Taliban promised to kill those Afghans who, the documents reveal, have collaborated with the Americans. President Obama said the leaks endanger the lives of American troops. Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor predicted the leaks will lead to a new free-speech ruling in the supreme court, which could overturn the precedent set in the Pentagon Papers case, the foundation of modern-day jurisprudence on questions of national security and freedom of speech.

Crescent, Oklahoma is stamped out in a one-square-mile rectangular grid and bisected by Highway 74, which becomes Grand Avenue in town. On this main thoroughfare is “the stop sign,” a frequently referenced landmark when locals give directions. There is the gas station, where men gather in the mornings to talk and drink coffee; the Baptist church – one of 15 churches in town – an unadorned, rectangular block, with a plain white spire and beige metal siding; Kelly’s Café, where locals fill the dining room to capacity at lunchtime. A towering, white grain elevator looms over the skyline. There are a few empty shells of buildings on Grand Avenue, but Crescent lacks the bombed-out look of crumbling decay visible in so many small Oklahoma towns. The cliché is unavoidable–Crescent, by all appearances, is a happy, healthy little town.

Crescent’s favorite son is Geese Ausbie, the “Crown Prince of the Harlem Globetrotters,” but there’s another character who isn’t as cherished, a 28-year-old woman who spoke up in 1974 and got the world’s attention.

Several miles south of town, on the Cimarron River, a decommissioned Kerr-McGee plutonium plant sleeps in quiet, conspicuous retirement. The plant was closed in 1975, a year after plant employee Karen Silkwood was last seen alive at a union meeting at the Hub Café (now closed, across the street from Kelly’s). After the meeting, Silkwood drove south on Highway 74 toward Oklahoma City to meet with a reporter from the New York Times allegedly carrying documentation of gross safety violations at the plant. Silkwood’s car was discovered crumpled in the embankment, its driver dead. The documents were never found.

An Oscar-nominated film was made about the incident, and the name Silkwood became a rallying cry for union organizers. But, for Crescent locals, the story is more than lore. Many in Crescent know someone who worked at the plant with Karen Silkwood, and for years the town’s residents shared an association with whistleblowing and martyrdom.

Perry’s Roadhouse is several miles south of town and effectively Crescent’s bar. Bumper stickers decorate a back wall: “Don’t steal, the government hates competition,” and “U.S. Government Philosophy: If it ain’t broke, fix it till it is.”

A scene from Perry’s Bar, illustrating the political atmosphere of Crescent. Photo by Michael Cooper.

Perry’s isn’t far from where Silkwood died on the same highway, and a few questions from a reporter still get locals speculating. An acquaintance says Silkwood was a drug addict. Perry heard that Kerr-McGee got the state to resurface the road, covering the skid marks before they could be analyzed. A friend of a friend says she backed into a telephone pole, putting the dent in her back bumper that, some believe, is evidence she was run off the road. Invariably, someone will add that Karen Silkwood was not from Crescent and lived in Oklahoma City.

The memory of the Silkwood incident lurks far in the background of life in Crescent–for the most part people don’t particularly care to talk about it, and, polite that Crescent locals are, when they do, most don’t have much to say. Still, the story remains unsettled. When Bradley Manning was growing up it was 20 years less settled.

Several miles north of Crescent, on Highway 74, a paved county road turns off the highway and into the countryside. The Manning family lived out here, in a two-story house in the country, near the end of a gravel road before it turns to dirt. Trees obscured the view of the house from the street and cast shadows over the property. There was an above ground swimming pool and a bountiful garden that produced what one neighbor called the biggest asparagus stalks he’d ever seen. The house was isolated and quaint. Neighbors were a quarter mile and more away. Brad grew up here with his older sister, Casey, his mother, Susan, and his father, Brian.

Brian Manning spent five years in the navy in the late 1970s, working with the high tech naval systems of the day. He studied computer science in California and went to work for Hertz Rent-a-Car as an Information Technology manager. While in the Navy he spent time at Cawdor Barracks, in Wales. He married a Welsh woman, Susan, and moved with his family to Crescent, from where he could commute to the Hertz office in Oklahoma City.

By all appearances, according to people who knew the family, Brian Manning, who did not respond to interview requests, was a difficult man to live with.

“He was just real demeaning,” said Rhonda Curtis, a neighbor. Another neighbor, who asked to be called James, put it more bluntly.

“Brian’s a dick.”

Brian Manning’s own words, however, contradict the image of a domineering jerk. While his son was in Iraq, in December of 2009, Brian posted on Brad’s Facebook wall:

“Happy Birthday Son!… Did your gift arrive? I sent it yonks ago.”

When Bradley returned home briefly on leave, in January 2011, his dad posted again, “Welcome back son!”

Less than a minute later, apparently after reading that his son’s profile listed Potomac, Maryland as his hometown, Brian added, “and your hometown is Crescent, Oklahoma.”

As a little boy, Brad was high-strung and abnormally intelligent. Like his parents, he has always been smallish.

“We used to think of him kind of like a cocker spaniel,” said Rhonda Curtis.

“He was just a little nerd,” said Danielle, Rhonda’s daughter, and a childhood friend of Brad’s. As kids, she and Brad rode bikes around the neighborhood, swam in his pool, played Super Mario Brothers at her house and Donkey Kong at his.

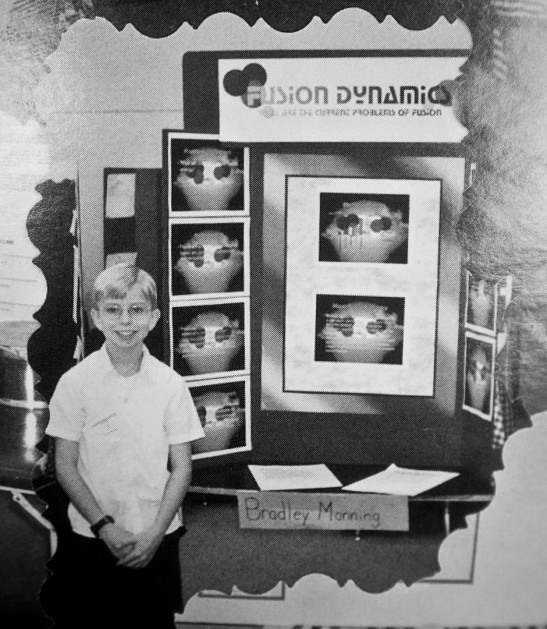

Bring up Bradley Manning in Crescent, and you’re likely to hear that he was, “too smart for his own good.” He was a promising saxophonist in the middle school band, always excelled in the science fair, and starred on the quiz bowl team. On bus trips to quiz bowl competitions around Oklahoma, he and a small group of friends passed the time talking about ideas and big picture questions of right and wrong.

“We’d talk about stuff that, for that age, was pretty deep,” said Shanée Watson, who recently graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “We discussed morality and philosophy a lot—I know that sounds weird, but that’s what we did.”

He was polite and obedient in class, with no disciplinary record at all from his elementary and middle school years. He did not, however, shy away from confrontation.

“You would say something, and he would have an opinion, which was a little unusual for a middle school kid,” said Rick McCombs, currently the school principal, who was a high school history teacher and coach when Brad was in school. “Don’t get me wrong, we had the cut-ups and the clowns and the mean ones and the bullies and those kinds of things, but this young man actually kind of thought on his own.”

While still in elementary school, Brad first expressed an interest in joining the U.S. military.

“He was basically really into America,” said his friend Jordan Davis, in an email. “He wanted to serve his country.”

Brad’s school bus ride home was an hour-long, and acquaintances say he spent most of the trip quietly doing his homework, while other kids had paper ball and spit wad fights.

Johnny Thompson, whose bus stop was last on the route, just after Brad’s, recalls a quiet but not exactly anti-social kid. “After everyone else was gone I’d actually go over there and talk with him a little bit,” Thompson said. “He was pretty nice if you were nice to him.”

As Brad got older his playfulness receded. He stopped playing with neighborhood kids, spending more time on the top floor of his home where he had his computer–this was the late 1990s, just as the Internet was becoming a truly global phenomenon, with, literally, a world of opportunity for a young man who felt increasingly alienated from the community he lived in.

Events in Brad’s life collided to put tremendous stress on the boy. As his peers were confronting their own sexuality in a context that was, at worst, prudish and ambivalent towards it, Brad was shouldering an added burden.

While Brad was in middle school, Brian Manning came home one day and announced he was leaving Susan. He moved out abruptly. Eventually, Susan and Brad moved into town, to a small rental house near the Baptist church. Brad’s grades dropped. Amidst the disintegration of his family, pubescent Brad was coming to terms with his own sexuality. Shanée Watson recalls Brad gathering she and Jordan Davis near a tree at Jordan’s grandmother’s house to give them important news. Brad told them that he would very shortly be moving with his mom to Wales for high school. He also told his two best friends he was gay.

This moment warrants pause. Bradley Manning, still effectively a boy, had few friends, and his family had all but fallen apart. In a time before Facebook and sustained long-distance friendships, he was leaving his two best friends for what could easily have been the last time (for Shanée Watson, it was). He didn’t need to tell them he was gay in order to confess a hidden affection, to explain a behavior, or even to allow his friends to know him better–in a short time he would be gone. And yet, presumably, for no other reason than that he was who he was and wanted to live honestly in his own skin, he felt compelled, in a conservative, religious town, to confide in his friends that he was a homosexual. Not only must it have taken tremendous courage for such a young man, it displays a crucial aspect of Brad’s personality. As his Facebook profile still says today, “Take me for who I am, or face the consequences!”

Brad moved to Wales with his mother to a much bigger small town, Haverfordwest, population 13,367, where he attended high school. He was teased for being effeminate but was not, apparently, open about his homosexuality. Friends say he was quiet, and kept his personal life to himself. He’d stopped playing the saxophone, got into electronic music and spent a lot of time on the computer. Though small and provincial itself, Haverfordwest must have been an exotic metropolis compared to Crescent.

After finishing high school, he returned to the United States, moved in with his dad in Oklahoma City, and went to work for Zoto, a software company. Brad’s strained relationship with his father cut that living arrangement short – the situation turned toxic, at least in part because of his homosexuality, and his dad kicked him out. He was homeless, moved to Tulsa, and stayed with his friend Jordan Davis. He eventually moved into a south Tulsa apartment near Davis’s, lived alone, and worked low wage jobs at F.Y.E., a retail entertainment chain, and Incredible Pizza.

Brad drifted from Tulsa to Chicago to Potomac, Maryland, in the outer suburbs of Washington, D.C. He moved in with an aunt and began to get a steadier footing. He had jobs at Starbucks and Abercrombie and Fitch, took classes at a Community College, and had enough money and stability to take a trip back to Chicago for the Lollapalooza music festival.

Not long after his trip to Lollapalooza, in the late summer of 2007, Brad joined the army. He’d long expressed interest in serving, and the army was a natural next step for an unsettled but talented and ambitious young man.

“I think he thought it would be incredibly interesting, and exciting,” Jordan Davis told me in an email. “He was proud of our successes as a country. He valued our freedom, but probably our economic freedom the most. I think he saw the US as a force for good in the world.”

Brad did basic training at Fort Leonard, in Missouri, but he sustained a nerve injury in his left arm, and his future in the army was put on hold. That Christmas on Facebook he posted cheerful pictures of a visit with his family in Oklahoma, including pictures of his father. After the holidays, Brad returned to basic training in Missouri. He graduated in April 2008 and moved to Fort Huachuca, in southern Arizona, excited to be back in contact with the civilian world. “Hit me up on the phonezors if you can!” he posted.

While at Fort Huachuca, Brad was reprimanded for putting mundane video messages to friends on YouTube that carelessly revealed sensitive information. The infraction must not have been serious, because by August he’d graduated from training as an intelligence analyst with a security clearance.

After Fort Huachuca, Brad was stationed at Fort Drum in upstate New York. It was an election year, and Brad was pulling for the celebrity freshman senator from Illinois, Barack Obama. Also on the ballot that year was California’s Proposition 8, which, in a significant setback for the gay rights movement, banned gay marriage in the state when it passed on Election Day.

Just days later, Brad went to a rally against Proposition 8 in front of city hall in Syracuse, New York, and an hour and a half from Ft. Drum. At the rally, a soldier was interviewed anonymously by high school senior Phim Her for Syracuse.com, a local news website. The soldier was Bradley Manning.

“I was kicked out of my home, and I once lost my job [because I am gay],” he told her. “The world is not moving fast enough for us at home, work, or the battlefield” Brad told her that, for him, the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy is the worst thing about being in the military. “I’ve been living a double life,” he said.

After Proposition 8 passed, Brad’s Facebook wall becomes a flurry of activity, much of it related to the gay rights movement, though most updates were ordinary messages from a happy young man, newly in love. He spent the holiday season in the Washington, D.C. area, and just before Christmas announced a relationship with a new boyfriend. He began posting more often than ever. “Bradley Manning is a happy bunny.” “Bradley Manning is cuddling in bed tonight.” For an active-duty soldier, he was remarkably transparent about his sexuality on his Facebook wall. After returning to base: “Bradley Manning is in the barracks, alone. I miss you Tyler!” And, “Bradley Manning is glad he is working and active again, yet heartbroken being so far away from hubby.”

Over the next several months, Brad’s posts are nearly all related to progressive politics or his boyfriend. He seems happy and confident, comfortable in his life, and positive about the future.

In September 2009, his relationship status changed to single, and posts between he and Tyler tapered off, though they maintained friendly communication. This was likely a safety measure in light of the Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell policy. A month later he deployed to Iraq.

Brad arrived in Iraq in late October 2009. His infrequent status updates are mostly mundane: “Bradley Manning has soft sheets, a comforter, and a plush pillow… however, the war against dust has begun,” and “Bradley Manning is starting to get used to living in Groundhog Day.”

After gay marriage failed on the ballot in Maine, he posted, “Bradley Manning feels betrayed…again.” In late November he posted, “Bradley Manning feels forgotten already,” but for the most part, he remained positive. The holidays brought a flood of well-wishers, but Brad was notably quiet. Considering what was to follow, Brad’s wall posts from this period are strikingly boring.

At the end of January 2010, Brad returned to the U.S. for a brief visit. He landed in D.C. just as a massive blizzard blanketed the city, and his plans were partly derailed. But as he left he wasn’t dispirited: “Bradley Manning is hopefully returning to his place of duty over the next few days. Hope I don’t get caught up in this next storm,” he posted on February 8.

This is the period in which Brad is accused of having leaked at least some documents to Wikileaks. Bradley Manning is officially charged with leaking classified information between November 19, 2009, and May 27, 2010. In his chats with Adrian Lamo, Brad references a “test” document he leaked to Julian Assange (presumably to verify Assange’s identity), a classified diplomatic cable from the U.S. Embassy in Reykjavik, sent January 13, 2010. Wikileaks posted the document on February 18, 2010.

If Brad was indeed the source of Reykjavik13, as the document has come to be known, he had to have leaked it sometime before mid-February, and Wikileaks tends to take time to analyze and verify the authenticity of leaked documents, if possible. Brad didn’t return to Baghdad from his visit home until February 11, and he left for home on January 21. If Brad leaked Reykjavik13, he almost certainly did so sometime over the eight-day period from January 13, 2010, when the cable originated, and January 21, 2010, when he left Baghdad for the United States.

The timing debunks the overarching narrative in the media that Brad was an anti-social outcast lashing out at the world and crying for attention when he decided to leak military secrets. On January 14, 2010, the day after Reykjavik13 originated, Brad posted, “Bradley Manning feels so alone,” to his Facebook wall–perhaps this is the period when he decided to become a leaker. He appears distraught, there is no doubt, but hardly the emotional wreck portrayed in the Lamo chats that took place months later.

Over the next several months, when Brad may have leaked most of the documents, he appears happy and carefree. His posts are peppered with smiley emoticons. On March 14, he “wishes everyone a Happy Pi Day!” Not until April 30, after a change in his boyfriend’s relationship status does his emotional state seem to deteriorate. That day he posts that he “is now left with the sinking feeling that he doesn’t have anything left…” Days later, on May 5, 2010, he says he “is beyond frustrated with people and society at large,” and the next day he “is not a piece of equipment.”

This is Brad’s last Facebook post. Later that month he apparently initiated a chat with Adrian Lamo, who had recently been profiled in Wired Magazine. Brad, it seems, broke down to Lamo and over a series of days confessed his shocking breach of U.S. military security.

The magnitude of classified material Brad is suspected to have leaked is astounding. He appears to have leaked the Collateral Murder video, in which American soldiers in an Apache helicopter gleefully gun down a group of innocent men, including a Reuters photojournalist and his driver, killing 16 and sending two children to the hospital, a video of the 2009 Granai airstrike in Afghanistan, in which as many as 140 civilians, including women and children, were killed in a U.S. attack on a suspected military compound, a cache of nearly 100,000 field reports from Afghanistan, known popularly as the Afghan War logs, about 260,000 diplomatic cables and a set of as many as half a million documents relating to the Iraq war that, even on their own, likely constitute the biggest leak of military secrets in history.

Lamo notified the authorities.

Brad’s Facebook status, on June 5, 2010, probably posted by someone else, reads: “Some of you may have heard that I have been arrested for disclosure of classified information to unauthorized persons. See [link to the Collateral Murder video].” He’d been arrested days before and was then being held in Kuwait, before being transferred to the brig at Quantico.

Brad currently faces three counts of unlawfully transferring confidential material to a non-secure computer–military jargon for leaking state secrets. If convicted, he could spend half a century in prison. U.S. Rep. Mike Rogers (R-Mich.) has called for his execution.

On July 25th, 2010, Wikileaks released the Afghan War Logs. The documents reveal hundreds of civilian deaths in unreported incidents, rapidly escalating Taliban attacks and indications that the Pakistani intelligence service, ostensibly a U.S. ally, works intimately and supportively with the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. The Guardian called the logs “a devastating portrait of the failing war.” The New York Times called them “an unvarnished, ground-level picture of the war in Afghanistan that is in many respects grimmer than the official portrayal.”

Critics of Wikileaks accused the group of publishing documents that included the names of Afghan informants, putting their lives in danger. Wikileaks withheld publication of 15,000 documents to redact the names of others to whom the leaks could bring harm, and claims to have invited the Pentagon to help—though the Pentagon denies this. The Pentagon has said that it will not cooperate with Wikileaks under any circumstances, has called on the group to stop publishing leaks, and demanded that it immediately return all classified material. The Daily Beast has reported that the Pentagon now has a 120-person strong “Wikileaks War Room” to minimize harm from the leaks, to try to preempt them and to collect information to be used, at some indeterminate future date, in prosecuting Julian Assange for espionage.

Wikileaks anticipated becoming an enemy of the state. Quietly and without fanfare, with threats to its existence rising, Wikileaks uploaded to its website an encrypted document called “Insurance file”, which has been downloaded more than 100,000 times to date. The file is about 20-times bigger than the Afghan War Logs. If – or when – Wikileaks releases the password for the file, the whole world will know what it contains. In Wikileaks, the Pentagon is confronting a challenge like none before. The agent was Assange, but the raw material likely came from Bradley Manning.

Since its debut on the world stage in 2006, Wikileaks has posted a document leaked from Somalia’s Islamist rebels, the contents of Sarah Palin’s email account, documents temporarily discrediting now-vindicated climate change scientists, internal papers from the Church of Scientology, the membership list of the pseudo-fascist British National Party and more. Big scoops all, but not until Collateral Murder and the Afghan War Logs did the American government initiate a concerted effort to shut the website down. Once a source of newsworthy if mostly innocuous revelations, Wikileaks has officially become a threat to national security. If the allegations against him are true, Brad made Wikileaks what it is today.

Crescent’s dilapidated former city hall, flanked by the old-town water tower. Photo by Michael Cooper.

The last day I spent in Crescent was a bright Sunday morning. I sat on a bench not far from the Hub Café, where Karen Silkwood spent some of her last moments. As trucks lumbered down Grand Avenue and drivers waved hello, the town came to life.

I went to Sunday school at the Baptist Church. In the class for young adults I attended, we discussed the familiar troubles of jobs, children and romance–troubles Bradley Manning is unlikely to experience for many, many years, if ever again. Toward the end of class we bowed our heads, and Rick McCombs, the principal of Crescent schools, led a prayer for Bradley Manning and his family.

After church, I spoke with Johnny Thompson, Brad’s old buddy from the long bus ride home. We met up at a gas station and talked about his life growing up in Crescent: the boredom, the tragedy of the closing of the arcade in the laundromat, the ridicule from kids in bigger cities, the independent streak instilled in him by being a social outcast in a small town. At the end of the interview, I turned my recorder off and started to stand. Thompson asked me to turn it back on.

“Just one last thing,” he said. “No matter what he did, every memory I have of him is just a little kid I talked with on the bus. It don’t even really seem right that he’s some big criminal right now.”

Thompson, a stonemason, has the hulking look of an overgrown boy soon to become a man. His dark, smoky eyes are fidgety and uncertain, betraying a humble, earnest sensitivity.

“I was worried that they might execute him.”

Thompson had caught my eye days earlier, when he mentioned in passing that he was reading the classic subversive novel written by Oklahoma City native Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man. I asked if I could interview him later. He said sure, then walked away. As I too walked toward my car, he turned and added, “Not everyone in Crescent’s a bunch of rednecks.”

Denver Nicks is a graduate of the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. His work has appeared in The Daily Beast, AlterNet, High Country News, and other publications. His next assignment takes him to Karachi, Pakistan, where he’ll be reporting for Express Tribune.