Quiet and introverted, Bob Bartholic was remarkably daring in his art and lifestyle. Often challenging traditional methods, he created avant-garde sculptures and striking paintings. From an oversized chess set that would fill a room with its towering pieces to a provocative painting that symbolized child molestation, Bartholic pushed his imagination into almost any realm.

In a 1998 interview with Steve Liggett and Walt Kosty of Living Arts of Tulsa, Bartholic, then 73, sits peacefully in front of the camera, his kind eyes looking out from behind big round glasses. His wife, Barbara Bartholic, made famous by her own art as well as her UFO investigations, leafs through photographs that she holds up proudly, providing evidence of their adventurous life together.

“Gay bars. That’s the only place where you could have any fun in Tulsa,” his wife blurts out as they discuss the 1960’s. She goes on to tell a long story about dancing with a man dressed in drag. “He had on a lot of pancake makeup, so when I danced with him, his makeup came off on my clothes. I thought it was really neat.”

The Bartholics surrounded themselves with Tulsa’s noted artists and thinkers—Paul England, Alice Price, Bill Rabon, Howard Witlatch, John Brainard. Together with their friends in downtown Tulsa, they started galleries, hosted parties and showings, painted murals and ran an explosively artistic television show called “Arts Arena,” with wild costumes including one made from glued-on cotton balls.

Always relaxed—in fact, for most of the interview he is nearly inaudible compared to the other speakers—Bartholic insists that he was never interested in traditionalism. “It’s not creative. It’s dull, to me, in comparison. Once that door [of abstract expression] is open for you, it’s a wonderful world.”

Recalling that interview in 1998, Steve Liggett remembers that Bartholic never showed any reservations about being different. “And he was never afraid to be poor, either.”

Bartholic’s oldest daughter, Chris Rodgers, remembers her father always recycling and using found objects for his art.

“He intended to make and construct everything from scratch. He always had a limited income, being an artist with eight kids. He’d go to thrift stores and buy artwork to paint over instead of buying new canvases.”

Rodgers also recalls the famous 56-foot boat her father constructed in Turley.

“I was just married, and I don’t know what started it. He got these plans and decided he was going to build a boat, like a big sailboat, with layers of chicken wire and cement. He tore apart old motorcycle crates for the mahogany, and even purchased a run-down building just so he could get the materials from it, to use for the boat.”

After more than a decade of work, when the project was nearly finished, it was destroyed by arson.

“The shell is still there, held up by trees that have grown around it. It’s actually spectacular,” Rodgers says. “People call it ‘The Ark.’”

Bartholic created the original “Stone Horse,” a sculpture of a horse head that has since been recreated multiple times, becoming an iconic symbol in the Brookside area. His paintings have been featured in galleries across town, often appearing in newspapers and magazines.

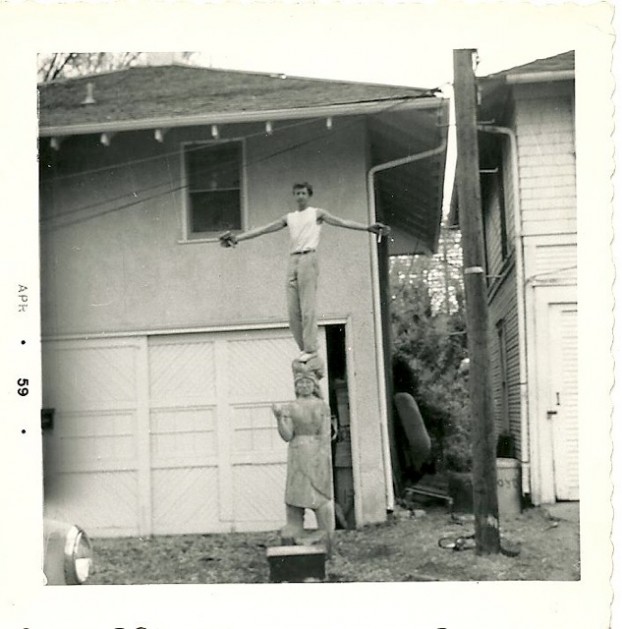

“My dad made it possible to be a man in another kind of way,” Rodgers reflects. “A lot of men—my husband, my sister’s husbands, other artists he was influencing—they’ve really thanked him for that. He liked to hunt and fish, but he was different, too. He liked being artistic and growing vegetables and taking care of his pond. I have a photo of him in college doing a performing arts piece in a painted-on costume.”

Sitting on a big beige sofa in 1998, Bartholic smiles into the camera. Though he remembers when shopping centers and corporate businesses took life from the downtown area, he insists it didn’t deter any serious art that was happening there.

“Artists don’t relate to cities in general. They relate to their own. I guess it’s a protective device or something, but you just live in that world of art, and everything else is just ‘them.’”