Most people dread the thought of prison. Claustrophobia, confinement, artificial and controlled light sources, concrete, stale air. On the contrary, I waited months to go to prison. I had been volunteering for a Peruvian man, Fernando “Coco” Bedoya, who began, in collaboration with the Ministry of Argentina in Buenos Aires, La Estampa, an art workshop that functioned inside the female prison called Ezeiza No. 3.

I was assigned to diligently catalogue every piece of literature that had been written about this collaborative over the seven years since the founding of La Estampa. Cataloguing and organizing, waiting for permission to be granted so that I could finally enter the compound that so many people dreaded visiting. A place where dreams die. And then I received word from Coco; I was granted entrance.

We sat on the train, Coco and I: he with his Einsteinian appearance of white, wiry hair and mustache, casually flipping through the paper, and me, cold and disheveled, nervously anticipating the institution.

From the station we took a cab to the perimeter of an immense plot of land that looked like an abandoned soccer complex covered with course yellow grass. We walked 200 meters to the first police checkpoint, a small kiosk situated between “out” and “in.” An officer took my passport and the admittance letter and we were escorted to the next checkpoint, near the entrance to the prison. I walked through a small scanning machine, left my cell phone and other belongings behind, and followed Coco in his labcoat through hundreds of steel bars.

The skeleton keys that opened each door were as long as my face. Through many cold corridors, we finally arrived at the studio. Women drinking maté, drawing, talking, twisting paper, making paper, painting, building frames. All the cogs of the machine that I was so familiar with were swinging and spinning, and occasionally interrupted by the clanking of an old grocery cart that was filled with cigarettes, chocolate, toilet paper, and other random goods that the girls could buy with their credit.

I sat down and spoke with Doris, a Peruvian jungle woman. We talked about the stars, as I was most intrigued by the night sky at this time. Doris and I share a favorite star, and a fascination with diamonds.

Some stars, instead of exploding or imploding or becoming black holes, simply lay down and stop breathing. Their massive carbon corpses slowly crystalize into a diamond skeleton. Jewels of the night sky that no longer glisten like sequins on evening gowns.

Doris was from a remote place in the jungle where folkloric tales were whispered to her by her aunt—tales in which animals possessed secrets and treasures, tales that she trudged through like toes through mud after a summer rain:

Walking eight hours through thick viridian tones, to a place where a waterfall sits on its throne of three converging rivers, snakes hold diamonds in their mouths … However, when the snake goes to bathe in the river it will leave its diamond on the shore … If you capture the snake’s diamond, you will be granted anything your heart desires … But the snake will chase you, for he is very fond of his diamond … With the diamond you must escape to the canopy of the trees …

Doris spent her childhood searching for the diamond of the snake, and many years of her adult life in prison, painting this scene—painting the night sky that she was no longer allowed to see.

Dear Doris,

I found your diamond in Thailand.

Love, Erin

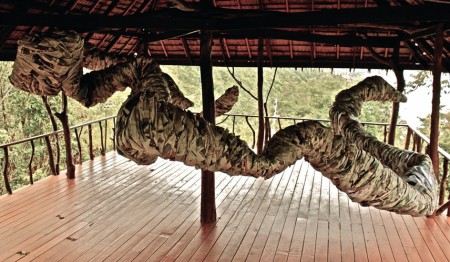

In a tree house, an open-air platform governed by the light of the sun, and breezing the ocean’s breath, a winged-serpent and her diamond were born. Fifty feet of chicken wire and newspaper swung and sung on the wind a song of the Ouroboros, the Phoenix, the Quetzalcoatl, the Snake and her Diamond. It is a song of rebirth, renewal, resurrection, the cyclical nature of life, immorality, the eternal unity of all things.

At sunset on October 24, 2011, at the Middle Way, on Koh Phangan, in Thailand, a group of 20 gathered for the exhibition of the “Snake and the Diamond.” We awaited the glistening stars of the night sky to light the massive serpentine beast. She was carried down to the beach, soaked with petrol, and sent to her fiery grave. It was a ritualistic burning that spoke to the ancient symbols of the song—a procession and process that united and ignited this group of people in the darkness of the new moon.

The burning lasted about five minutes, giving the nearest neighbor ample time to rush to the conclusion that a brush fire was about to consume his home. The panicked expat and his Thai wife came running down to the beach (where the group found themselves entranced by the flames) screaming such phrases as, “Respect Thailand!”, “Is this some yoga bullshit!?”, “Would you do this in your own country!?” Well, yeah, of course I respect Thailand, no it’s not some yoga bullshit, and yes, I have definitely done this in my own country. In fact, this is the third sacrificial paper sculpture I have burned.

Rumors of naked hippies, forest fires, and pagan rituals spread like wild fire around the local hangouts and hubs on the island. Like any small community, gossip keeps people alive and well in the most boring of moments.

Only the faint smell of petrol, seeping like whisky from the skin the day after a hard drink, was left on the boulders where the smolder occurred. When the police and the mayor arrived the following day, they found only a few leaves that were charred from a tree that was watching too close to the flames. No traces of Quetzalcoatl, Ouroboros, Phoenix, or the Snake and her Diamond were left on the beach because, as everyone knows, from her ashes she will rise.