Editor’s Note: Names of victims have been changed.

Many are the afflictions of the righteous, but the Lord delivereth him out of them all. – Psalm 34

No more sleepovers. No more babysitting, or car rides home. No more being alone with children or “lingering hugs given to students (especially using your hands to stroke or fondle).” Aaron Thompson—Coach Thompson to his PE students—sat in the principal’s office at Grace Fellowship Christian School as his bosses went through the four-page Corrective Action Plan point by point. It was October of 2001, the same month Aaron added “Teacher of the Week” to his resume.

Grace’s leader, Bob Yandian—“Pastor Bob” as everyone calls him—wasn’t there: no need, he had people for this kind of thing. Pastor Bob’s time was better spent sequestered in his study, writing books and radio broadcasts. His lieutenant, Associate Pastor Chip Olin, was a hardnosed guy, “ornery as heck,” people said. Olin brought a USA Today article on the characteristics of child molesters to the meeting. At age 24, Olin explained, Aaron was acting immature and unprofessional, and someone might get the wrong idea.

The first two recommendations of what became known as the “do not fondle” agreement were prayer and “building relationships with young men and women of your age group in Sunday School and Singles group activities” at Grace Church, which ran the school. “Leaders in the kingdom are judged not so much by what they accomplish as by the character they reveal—who they are before what they do,” the document continued (pages 1, 2, 3, & 4). Aaron was to “live a lifestyle above reproach”—to act such that no one would question his character.

Associate Pastor Olin let head administrator John Dunlavey, Aaron’s other boss, do much of the talking. Olin had only just read the Corrective Action Plan for the first time as he walked down the hall en route to the meeting. He was mostly there as an observer. It was Dunlavey’s brainchild, after all.

Dunlavey didn’t mean that kind of “fondle.” He tacked it on, thinking it best described the overly affectionate hug-plus-hand-stroking he saw Aaron give a boy one day at lunch. With his big, square glasses and brow that furrowed in concentration, Dunlavey was more the earnest science teacher he once was than the administrator he’d become. He looked up “fondle” in the dictionary, and it seemed the most precise. Science guys love precision.

Dunlavey didn’t think babysitting and all the rest were problems, just symptoms: Aaron had become too close to Grace families. Misplaced loyalties. That was the real issue.

Young boys were leaving Grace over the past few years, and no one knew why. One boy moved a full 1200 miles away. He still skateboarded with friends and did normal kid stuff, but he was having horrible nightmares and failing classes, unable to contain his inexplicable fury at teachers. At one point, he told his mother he couldn’t stand how he felt and no longer wished to live. But Grace’s leaders would not know or would not admit such things about their flock until much later.

* * *

Grace Church sits atop a hill just south of Tulsa, off a two-lane country road with a speed limit of fifty. The boxy, tan bunker of a building has flagpoles at the entrance, making the church look like a fortified post office. Eighty acres of grassy fields spread out below. Houses in the area range from spacious to McMansion, and new developments get names like Ridgewood or Shannondale. In the incorporated suburb known as Broken Arrow, Oklahoma, the ratio of car dealerships to churches is about 1:1. The nearest strip mall to Grace has a drive-thru Starbucks, a Walmart, and a fast food chicken restaurant that pipes soft Christian rock over speakers into the parking lot. Such is the way of Tulsa geography: blacks to the north, Latinos and Asians to the east, miscellany in midtown, and evangelicals and big box stores in the south.

Fall of 2001 was the grand opening for Grace’s new children’s building, a real beauty, the pride and joy of the whole church. “Grace is the place for kids” was the church’s slogan back then. The new, 56,000-square-foot building had two stories of classrooms, plus amenities like a Chuck-e-Cheese-style room with tubing and a ball pit, “Bob and Loretta’s Soda Shoppe” (an old-fashioned ice cream parlor named after Pastor Bob and his wife), and the crowning glory: an antique carousel beneath a vaulted glass pyramidal ceiling. Bejeweled with big amusement park light bulbs, the carousel’s gold and aqua paneling positively glowed: $125,000 well spent. Grace took out a $7.5 million loan to finance construction of the children’s building, and when all was said and done, the whole thing was worth nearly $10 million—over half the value of all their buildings combined. In time, a new auditorium would be built, too, which would connect the children’s building to Grace’s main wing. They began a fundraising campaign back in 1998: “Investing in eternity.” That was the year Pastor Bob published his book Righteousness: God’s Gift to You. “You don’t need to crawl on your knees or do any ‘good works’ to try to earn God’s approval,” Pastor Bob promised.

Aaron Thompson was the teacher all the girls had crushes on and all the boys idolized. The younger kids mobbed him around campus and clamored for hugs. His smile was radiant, his Believer’s pedigree sterling. Aaron had grown up at Grace Church. In high school, he was senior class president and a star basketball player, before heading to nearby Oral Roberts University. Parents frequently had Aaron over for dinner, asked him to babysit, or hoped he could stay with the kids for a week while they went on vacation. Aaron fielded invites for family outings big and small, from camping trips to ice cream at Braum’s after church. Parents were delighted to have a young man like Aaron in their children’s lives. He was the golden boy of Grace Church.

And yet, in August of 2001, prior to the signing of the “do not fondle” agreement, Grace received an unsigned letter. It read:

“This is a matter of life or death for a child or children. People have been known to commit suicide for this very reason … everything you need to know will be revealed if you will monitor the boy’s locker room and private hallways or areas when no one is around, especially before and after the PE classes. Watch your staff when they are alone with young boys, even for two minutes. Ask yourself, ‘Why have certain boys left Grace?’ and ‘Why are some boys tardy often?’ ”

Olin didn’t think the letter was about Aaron to begin with; Dunlavey came to agree as the meeting with Aaron wore on. Yet still, Dunlavey thought, perhaps Aaron’s behavior was being misconstrued somehow, and so he read the letter aloud.

“Aaron, is this you?” Dunlavey asked. “Are you doing anything that might cause somebody to write this kind of a letter?” Aaron assured them he was doing no wrong. He was repentant, open to correction. Olin had high hopes for Aaron. Everyone did. For the remainder of the school year, Aaron was on probation. Violation of the agreement would mean termination. Olin, Dunlavey, and Pastor Bob would discuss Aaron’s progress during their weekly meetings.

Aaron left Grace and headed to Cheddar’s, a nearby restaurant, to meet with the teachers on his unit. They were the Specials Teachers, the “Special Ts,” they called themselves, a tight-knit crew that taught subjects like PE, music, and Spanish—all women except for Aaron. Aaron plopped down in the booth, late and very upset. “What’s wrong?” asked Laura Prochaska, the computers teacher. “We’re your sisters. Talk to us.”

Aaron swore them to secrecy, then confided that Grace made him sign papers saying he could never take kids to the movies or babysit or hug them. “I can’t be their big brother,” he lamented.

“Just don’t do anything questionable that they could get you for,” Prochaska advised. “They must not think it’s such a big deal, but they want to protect themselves by having you sign this contract.”

“Maybe you should think about quitting,” another teacher added, encouraging him to take the protest route.

“No, no. I’m not a quitter,” Aaron told them. “I’m going to see this through.”

The “Special Ts” didn’t know he’d already been molesting children at Grace for years. From that day in October until his arrest on March 25, 2002, Aaron Thompson would sexually abuse four more boys. One of them was the son of a teacher sitting there in the restaurant booth.

* * *

This is a cautionary tale. It is about deference to authority, and denial, and the human cost of privileging an institution above people. According to Oklahoma law, anyone having “reason to believe” that a child is potentially being abused must make a report to the Department of Human Services or the police. Child abuse experts urge us to follow the law and not take it upon ourselves to evaluate or investigate allegations or suspicions of abuse. But that is exactly what Grace did. And they reaped what they sowed.

Grace Church was Oklahoma’s Penn State of 2002. After such things come to light, we always wonder: how on earth did that ever happen?

Here is how it happened.

The public record is suspect when it comes to what was going on behind the scenes at Grace before Aaron’s arrest. For starters, don’t trust what I just told you about the signing of the “do not fondle” agreement on that day in October 2001. All that was reconstructed from the testimonies and depositions that head administrator John Dunlavey, Associate Pastor Chip Olin, Principal DeeAnn McKay, and Pastor Bob later gave during the negligence lawsuits in which Grace became mired. The only problem is that what they said under oath doesn’t square with the recollections of two teachers who were sitting in the restaurant booth with Aaron immediately after he signed the agreement.

During the lawsuits, everyone at Grace said the Corrective Action Plan was Dunlavey’s idea—they simply followed his lead. (Pastor Bob said he green lighted Dunlavey’s idea in advance, got the executive summary of Dunlavey’s text afterward from Olin verbally, and only read the actual document following Aaron’s arrest.) And yet, Laura Prochaska and another Specials Teacher who spoke on condition of anonymity distinctly remembered Aaron telling the group, “Chip [Olin] made me sign this thing.”

The second teacher had been a member of Grace Church for decades. “Knowing all the personalities as well as I do, John [Dunlavey] would not have come up with something like that. That was a Chip thing,” she assured me. “If [Dunlavey] had had to write an agreement, it would’ve been dictated to him by Chip Olin,” she added. “They liked puppets around there.”

The Corrective Action Plan was just one plot point in the whole story. Who knows what else didn’t quite happen as Grace said it happened? Conveniently, Grace’s version of the story protects the man at the top.

Pastor Bob has long been a pillar of the national charismatic Pentecostal community. Colleagues describe him as “a pastor’s pastor,” a wingman for the mega pastors. Decades ago, Pastor Bob was Dean of Instructors at RHEMA Bible Training Center while founder Kenneth Hagin Sr. pioneered the hugely influential Word of Faith movement, which teaches that the Lord blesses the faithful with healing and financial rewards (provided they tithe). Today Pastor Bob is a board member of Joyce Meyer Ministries, which brings in about $100 million in donations annually, affording Meyer the luxury of traveling by private jet.

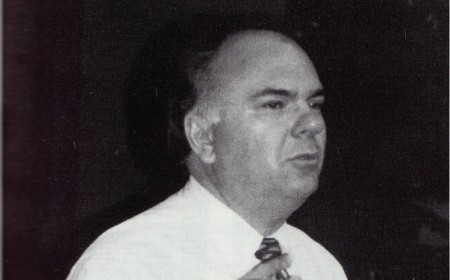

At Grace, the stage is dark and bathed in soft pastel lights when the eleven-member worship band leads the congregation in the gentle murmuring called talking in tongues. But when Pastor Bob takes to the pulpit, on come the harsh fluorescents: it’s business time. Pastor Bob, ruddy faced and paunchy, preaches the prosperity gospel of health and wealth. His eyes narrow as his nasally voice rises. He even incorporates his love of fancy cars into sermons. He has owned several over the years, including a pair of his-and-hers BMWs. Pastor Bob bought his wife’s beemer, and Grace bought his. Pastor Bob is known for his “practical wisdom.”

The first lawsuit, John Does 1–7 versus Grace, went to trial in September 2004. [1]

“I don’t really make ‘Chip’ decisions,” Associate Pastor Chip Olin testified. “I’m an extension of Pastor Bob.”

* * *

Maybe it began with the tittytwisters. Or the tousled hair, the hugs, the body slams.

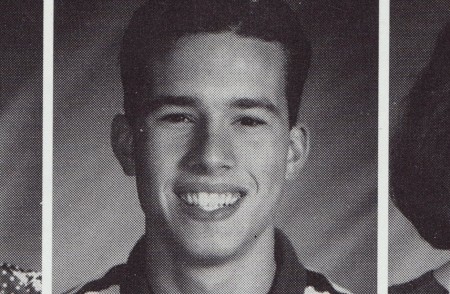

“Older brother-type stuff,” Josh remembers. “He would slowly desensitize you.”

Josh was Aaron’s first victim, although of course he didn’t know it back in 1996. Aaron would ask him to stay after gym class to help put away PE equipment.

Josh and I are sitting in a Mexican restaurant in downtown Tulsa, next to a mock-up boxing ring that has been incorporated into the décor. His bicycle is locked up outside. Josh wears a jean shirt with pearl buttons and rolled sleeves. He is quick to smile and has a little stubble, a handsome twenty-something. An autodidact since high school, Josh just sent off a round of out-of-state college applications. We compare notes on the arduous application process before hunkering down to talk about what we came here to talk about.

It was the end of fifth grade, and Josh was 11 years old. He was a cute, happy kid with a toothy grin and a center part in his hair, the 1990s style that made little arches on either side above the forehead. Josh’s father died a few years earlier. Now Josh wonders if it made him vulnerable, eager to latch onto a male figure, someone to connect to, hoping to please the golden boy of Grace Church.

“We had played dodgeball, and he asked me to bring in all the stuff with him,” Josh begins to tell me. “When I was in the closet putting things away, he came up behind me and grabbed me and slid his hand down and touched me.”

Afterward, Aaron told Josh to go to the nurse and get an Advil, a cover for being late. He spent all of the next class staring silently into space, trying to process what happened. From there, it escalated. During Josh’s fifth and sixth grade years, this became just about a weekly occurrence. In the supply closet by the gym, in the gym itself, in the coach’s office that locked from the inside, in the boy’s locker room that connected straight into the coach’s office. Aaron’s hand down Josh’s pants, Aaron’s hand putting Josh’s hand down his own. Josh started to get used to it.

Josh became withdrawn, jumpy, and moody. His parents didn’t know what to make of his drastic personality change but assumed it was just a phase. He couldn’t concentrate. That was the year he got misdiagnosed with Attention Deficit Disorder.

Like most abusers, Aaron was very skilled at coercing his victims into cooperating with their abuse. Josh felt guilty: he’d gone along with it. And Josh knew God knew.

For evangelicals, God is a personal God, there with you in every moment. Josh worried and worried: what did He think of him? It was a gut anxiety, ever-present. He hoped, desperately, that God would help him or guide him somehow. Josh did what he had been taught to do when he didn’t know what to do: he prayed. He prayed constantly. But deliverance never came. He was 11, maybe 12. Josh found his mom’s handgun and placed the barrel into his mouth. This way, he thought, he’d get to be with his dad again. When he finally got up the nerve to pull the trigger, nothing happened. It wasn’t loaded. Josh took it as a sign. He didn’t try again ’til years later.

The escalation continued. Before long, Aaron was having Josh perform oral sex on him and doing likewise to Josh. If it came out that this was going on, Josh knew he would be the talk of the school. Children are cruel, and Christian children no different. He liked it, they’d taunt. Walking down the hall, it felt like kids were staring at him. Surely they could tell, surely they knew that Josh had brought this on himself. Aaron had convinced Josh that Aaron was keeping Josh’s secret.

Throughout it all, of course, Josh was still being asked to help put things away after gym class: he was needed and wanted and chosen. Abuse binds the abused to their abuser, power and control the engine driving all.

“He made you feel—” Josh pauses to find the word for the memory. “Special.” Aaron treated him like the adult that he was not.

Sometime in seventh grade, Josh’s face, neck, and back broke out with blistering, painful acne—in all likelihood a product of stress. But also puberty: it was 1998, and Josh was thirteen. The abuse tapered off.

Time passed. Josh drew into himself. Eventually, he started noticing younger boys coming out of the gym, late for their next class. Boys who seemed to have special friendships with Aaron. And that’s when it hit him: there were others.

Aaron went way back with Grace’s youth pastor and basketball coach, Mike Goolsbay, a big teddy bear of a man with spiky gelled hair who was always saying “bless you, kiddo” with gusto. Goolsbay had known Aaron since he was a 13-year-old in Grace’s youth group. Aaron knew he could call Goolsbay late at night if he ever needed an ear, like the time his senior year of high school when he had some teenage angst to hash out, or the time in college when a girl broke his heart. Goolsbay was the one who asked Aaron to start helping out during Grace’s summer camps.

During the 1995–1996 school year, while Aaron was a freshman accounting student at Oral Roberts University, he volunteered as the assistant basketball coach/assistant youth pastor at Grace—Goolsbay’s right-hand man. By all accounts, the first failure to report child abuse at Grace came in early 1996, around the time Josh’s molestation began. Dr. Mark Peterson [2] and his wife brought Goolsbay a printout of emails Aaron sent to their seventh grade son, who was on Goolsbay’s basketball team. One email described the son’s genitalia and called him a “stud.” The emails were all signed “Love, Aaron”—not, Peterson noted, “Love in Christ, Aaron.” (Child abuse experts say that lewd emails constitute abuse.) Peterson insisted that the emails be made part of Aaron’s permanent file. Goolsbay agreed to do so, using the exact same logic of denial and negligence that everyone at Grace would deploy in the years to come: Aaron is unprofessional, he’s immature, I’ll counsel him, and all will be well. (Had Goolsbay followed state law, he would have called DHS or the police.) Goolsbay says he didn’t tell any of his superiors about the incident, and the emails were never found in Grace’s files.

Meanwhile, Pastor Bob‘s book, One Flesh: God’s Gift of Passion—Love, Sex & Romance in Marriage, became a hit. (A blurb on the back from Oral Roberts surely helped.) “When you have a strong relationship with your mate’s soul,” Pastor Bob advised, “the relationship with his or her body becomes something fantastic!”

Aaron became Grace’s part-time assistant athletic director in 1997, and in late 1998, shortly before he graduated from ORU in the spring of 1999, he was hired as a fulltime PE teacher at Grace—on Goolsbay’s recommendation.

After Aaron’s arrest, Dr. Peterson called Goolsbay to remind him of the emails. Goolsbay was defensive, and the conversation grew heated, Peterson later testified. “CYA”—Cover Your Ass—was “the feeling I was getting,” Peterson said.

* * *

Long before any sexual abuse came to light at Grace, Dr. Gene Reynolds, a Tulsa psychologist, remembered trekking out to the school on Garnett Road, asked by parents to evaluate this or that kid for issues unrelated to the abuse. He was struck that the administration and staff seemed totally unreceptive to professional recommendations.

“They had their own ideas about what needed to be done,” Dr. Reynolds noted.

He ended up examining seven of the Grace boys Aaron abused. In the boys’ pre-teen and teenage years, the early effects of trauma were varied: the gamut ran from severe anger to depression, suicidal feelings and attempts, insomnia, fear of men, panic attacks, feeling like “damaged goods,” shame, guilt, early sexual activity and promiscuity, incarceration, and drug abuse. “There were some boys who said they never wanted to set foot in a church again,” Dr. Reynolds added.

Late effects of abuse vary individually, but the numbers are grim: victims of abuse are more likely to have trouble in school (a 50 percent chance); more likely to develop substance abuse or mental health problems (one study found 80 percent of 21-year-olds who’d been abused had one or more psychiatric disorders); and 5-8 times more likely to experience major depression in their lifetime. Both depression and substance abuse are associated with poor treatment outcomes when patients have histories of child abuse. Men who’ve been abused as children are 3.8 times more likely to perpetrate intimate partner violence as adults. Adults who’ve been abused as children are twice as likely to attempt suicide—and twelve times more likely to commit suicide. The sooner abuse is detected and treated, the better the child’s prospects are in the long term.

The men who sexually abuse children—and they are mostly men—are often the last people on earth you’d ever imagine. About 90 percent of child sexual abusers are people the victim knows. About 30 percent of abusers are relatives—a father, older sibling, a favorite cousin or uncle, the people you trust most in this world. About 60 percent are outside the family—coaches, teachers, Scout leaders, ministers, neighbors, family friends, teenage sons of family friends: the authority figures children look up to. Abusers work their way into positions where they’ll have access to children, so that they become the “not in a million years” people. This is exactly why state laws do not allow individuals or organizations to “handle” abuse complaints or suspicions on their own: these bonds of trust make it impossible to respond to potential abuse with anything but disbelief. Outside authorities, by comparison, don’t have such preconceived notions.

Girls are victimized more often than boys, but boys are more likely to be victimized by a non-family member. Underreporting is common, making data hard to come by, but studies suggest 25 percent of women and 16 percent of men were sexually abused before age 18 (including peer abuse). According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, “The children most susceptible to these assaults have obedient, compliant, and respectful personalities.”

At Penn State University, allegations of former assistant football coach Jerry Sandusky’s sexual assault of a child traveled from graduate assistant to head coach Joe Paterno to athletic director and University vice president and president. Everyone, it seemed, was willing to report a coach up the chain of command and assume they’d done their due diligence.

For decades, Catholics moved their pedophile priests from one community to another, dumping them on unsuspecting parishes. The Catholic Church spent the ’90s doling out cash settlements to sexual abuse victims, who were required to sign confidentiality agreements. The eruption of scandal was to be avoided at all costs. Defrocking was unheard of: priests had repented, and that was that.

Then, a 2002 Boston Globe investigation blew the lid off of everything. Just as the Catholic clergy abuse scandal was breaking, Tulsa became likewise embroiled. While the Catholics shuffled their perpetrators from parish to parish, Grace harbored Aaron. In this way, the evangelicals of South Tulsa were much like the ultra-Orthodox Jews of Brooklyn, who have kept their abusers within the tight-knit community.

In the experience of Roy Van Tassell, an abuse specialist at Family and Children Services of Oklahoma, Grace was not all that unique among some kinds of religious institutions locally.

“They tend to be more autocratic, more cloistered,” Tassell told me, “and there is some anecdotal evidence to say that those communities tend to be at somewhat greater risk.”

“It happened because Aaron Thompson was a member of our family,” the church’s lawyer told the jury during the John Does 1–7 versus Grace trial. Family ties both bind and blind, the lawyer seemed to be saying—a truism that fits most all communities.

* * *

“The only assurance of our nation’s safety is to lay our foundation in morality and religion [Christianity].”—Abraham Lincoln, as quoted by the Grace elementary school handbook

At Grace Fellowship Christian School, everything from “the World”—that is, the secular world beyond South Tulsa—was suspect: Harry Potter, Tim Burton, whatever clothing happened to be in style that year. But students were led in prayer for the World: that the spiritual enemy known as Bill Clinton would be replaced with a godly leader; that Senator Jim Inhofe would be reelected; that George Bush would lead our great Christian nation and glorify His kingdom.

Federal laws prohibit partisan political activity in churches and other tax-exempt organizations. Yet, Grace encouraged students to volunteer for Republican election campaigns, sometimes offering extra credit. One year, Grace students went on a field trip to hammer lawn signs for Representative Steve Largent, an original member of the C Street house in Washington, run by the powerful and secretive fundamentalist Christian group known as the Family (perhaps best known as the incubator for Uganda’s “kill the gays” bill). Former Grace students and parishioners remembered that Largent and Senator Don Nickles, another Family member, were frequent guests at the school. Also a Family man, Inhofe has graced Grace’s pulpit many times. For a number of years, Grace donated money to Christian Embassy, one of the Family’s sister organizations that ministers to Washington elites. It was a Christian Embassy evangelist who led Inhofe to dedicate himself to Jesus in a congressional dining room in 1988.

In an email, the office of Winters & King, Inc., Grace’s attorney, said the church “has no relationship with Steve Largent, past or present.” The email continued, “Grace has no relationship with Senator Inhofe except to pray for him as mentioned in I Timothy 4:1-2”—the same answer they gave for District Attorney Tim Harris. The verse from Timothy reads, “In the latter times some shall depart from the faith, giving heed to seducing spirits, and doctrines of devils.” Stay the course, Grace apparently prays for Christian conservative politicians.

“As we go we follow Jesus,” went the Grace school song. “His Holy Spirit guides the way.” The way was one of structure and discipline: wear pants the wrong color of blue, and you could end up with in-house suspension, be given a pair of headphones, and made to listen to tapes of Pastor Bob’s lectures. Chewing gum as a repeat offense could mean a paddling in the principal’s office; girls had to kneel in the entryway of the school to make sure their skirts touched the floor; only one What Would Jesus Do bracelet was allowed: excess was vanity.

At Grace, the bodies of the young were policed with the utmost of vigilance. When a ninth grade girl kissed a seventh grade boy on the cheek, he was suspended and banned from sports tryouts. Shaming was a teaching tool. When a 15-year-old girl got pregnant, her expulsion was announced to the whole school in chapel, with her younger sister sitting there in the pews. The infractions of children—major, minor, and everything in between—were punished swiftly and severely.

“It was definitely a dictatorship,” remembered one Grace teacher who was a church member for over thirty years.

* * *

Grace had an application for volunteers to fill out, with a part that asked if they experienced sexual abuse as a child. An affirmative answer rendered a volunteer ineligible to work with children. Way back in 1995, Aaron answered “no.” But one day toward the end of the summer of 2000 or 2001—Goolsbay couldn’t remember which year—on a long car ride to a campground in Tahlequah where Grace held summer camp, Aaron confided in him. The real answer was “yes.” Teenagers molested him when he was four. (Aaron later testified that he was molested again at age 16 by a youth pastor at a different church.)

The two talked the entire car ride, over an hour and a half. Goolsbay was relieved when Aaron told him that his parents found out about the abuse sometime in middle school— it hadn’t remained a festering secret. But, at the same time, Goolsbay understood that victimization could be a cycle.

“Aaron, do you struggle with this in your life?” he asked. “Is this ever something that you’ve duplicated or acted out on?” Perhaps Goolsbay should have had thoughts along these lines back in 1996, when Aaron sent lewd emails to a seventh grade boy.

“No, no, I would never, ever do that to a child,” Aaron assured him.

Goolsbay thought about Aaron teaching every single child at Grace, preschool through eighth grade, including his own children.

“Are my kids safe, as well as every other kid safe?” Goolsbay wondered to himself.

“I felt like he gave me that assurance,” Goolsbay later testified. He told Aaron he was there for him if he ever needed to talk. Goolsbay says he didn’t bring up the lewd emails to the Peterson boy, and he didn’t think to recommend professional help. After that, whenever they saw each other around Grace, which was just about every day, Goolsbay would put his arm around him and ask, “How is your heart?”

Around this period, Aaron, as a counselor, molested two Grace students at Camp Dry Gulch, where many Grace kids went.

Despite Aaron’s own history as a victim of sexual abuse, Grace continued to let Aaron work with children. Goolsbay claimed he never reported that conversation up the chain of command. Grace purged Aaron’s volunteer file in 2001.

In 1998, Laura Prochaska became the computers teacher at Grace. She started noticing that certain boys used to arrive late. Again and again and again, the same boys. She’d ask them where they were, and they’d answer that they had been helping Coach Thompson put away equipment after PE—or at the nurse’s office. Then they would sit the entire period, staring blankly at their computer screens without even turning the monitor on. After class, she’d pull them aside.

“What’s wrong?” she’d ask them. “Are your mommy and daddy having trouble at home?” To no avail.

Prochaska went to Mary Ellen Hood, the elementary principal at the time. Hood was gung-ho about Christian education as a calling; Grace was her life. She wore a blue blazer emblazoned with the school crest.

“I said, ‘I’ve got some kids who are coming late, they’re sullen. I try to talk to them after class, they just stare down at the floor and don’t say anything except, ‘I’m OK, I’m OK,’ ” Prochaska remembered telling Hood. (When I called Hood in March 2012 and read her this quote, Hood paused a full five seconds, cleared her throat, thanked me with a “bye now,” and hung up.)

At the time, Prochaska said, Hood apparently never followed up. This was all happening while rumors were circulating— malicious rumors, or so it seemed at the time, that Aaron was molesting boys. Without any formal complaints, Prochaska and the other teachers dismissed it as “just talk,” she said. “We blew it off, thinking, ‘Oh my gosh. What is this? A frustrated kid that wants to get back at his coach? Or a frustrated parent that wanted to attack the coach?’ Because he was a man of integrity, as far as we knew.”

Prochaska was the unit leader for the Specials Teachers. In retrospect, she marvels that the principal didn’t have her monitor Aaron. “I guess Mrs. Hood gave Aaron the benefit of the doubt and thought she could handle it on her own,” Prochaska said.

Prochaska didn’t know reporting protocol because Grace hadn’t trained her to know it: those rumors of child sex abuse—“smack talk” about Aaron—were grounds enough for a call to outside authorities. Reports to DHS can even be made anonymously. But it was a culture in which the World was not to be trusted or called upon. One’s responsibility was to the chain of command.

Under Oklahoma law, the Child Abuse Reporting and Prevention Act, it is a misdemeanor for anyone “having reason to believe” that a minor is potentially being abused to not report it to the Department of Human Services (DHS). (In at least three states, failure to report child abuse can result in a felony.) In some states, the legal requirements to report abuse are limited to certain professionals like health care workers and school employees, but Oklahoma is one of 18 states in which everyone is what’s called a “mandatory reporter.” The reporting obligation is individual, meaning that it’s not enough to simply alert one’s superiors and have them make a decision about whether or not to call outside authorities. DHS investigates abuse within the home and refers cases like that of Grace to the Tulsa Police Department (TPD) for investigation. When rumors were spreading at Grace, anyone could’ve alerted DHS or TPD. Then, hypothetically, TPD would’ve gone out to Grace to “turn over every stone, ask every question,” said TPD spokesman Jason Willingham. “We’re going to ask, ‘Hey did you ever see anything unusual?’ It’s the little things that just didn’t add up.”

District Attorney Tim Harris handled Aaron’s case. He never returned my phone calls. I left messages asking him to explain why he didn’t prosecute Grace for failing to report child abuse. Harris once said, “As a criminal prosecutor, I look at the Ten Commandments.” Harris and Mike King, Grace’s lawyer, were classmates of Michele Bachmann’s in law school at Oral Roberts University, which promotes a biblical interpretation of secular law in an effort to undo the separation of church and state.

Roy Van Tassell of Family and Children’s Services of Oklahoma said failure to report prosecutions were “rare” in his experience. Nationally, successful failure-to-report prosecutions are few and far between. They typically result in a fine of a few hundred dollars, if that. “If any good would come out of any of this,” one father of an abused boy at Grace told me, “it’d be that somehow, somewhere, laws would be changed.” He suggested a fine of $10,000 for every day someone fails to report child abuse.

There is a big shortcoming in Oklahoma’s current law: “reason to believe” can be read subjectively. The statute states, “Any person who knowingly and willfully fails to promptly report any incident” may be charged with a misdemeanor. “As a practical matter, unless someone made an admission … that they knowingly and willfully failed to report as required by law,” a DHS representative told me, “how would we know?”

According to the plaintiffs’ lawyers, all Grace had to do to avoid prosecution was say they didn’t have any “reason to believe” and didn’t “knowingly” fail to report that Aaron was molesting boys. They didn’t have any reason to believe it, because they chose not to believe it.

In a recent phone conversation, Grace’s lawyer, Mike King, reiterated his interpretation of the law. When an organization receives an abuse complaint, King said, “If they have reason to believe that that report is true, they should report it [to DHS].” Yet, credibility is beside the point. That’s for the World to discern.

At the time, Prochaska didn’t know about all the parental complaints Grace was receiving. Sometime during the 1999–2000 school year, a father came to Mary Ellen Hood to complain that Aaron showed up at his house one afternoon, wanting to treat his son to lunch. The family just moved, and he had no idea how Aaron knew where they lived.

“I don’t want my son around Aaron Thompson,” he told her, asking for the boy’s removal from Aaron’s PE class. Hood refused, thinking his concerns irrational: teachers walk students to and from gym class, she said, and there was no way his son would be alone with Aaron. (Little did the father realize, his son was regularly late to Prochaska’s Computers class. Which is to say he was among the victims.) Hood told the father not to worry: everyone at Grace had known Aaron for years and years and years.

Privately, however, Hood met with head administrator John Dunlavey—instead of going to the authorities. They told Aaron that under no circumstances was he allowed to be alone with children off-campus. None of the other teachers at Grace were informed, and no paperwork to this effect was ever found in Aaron’s file.

In September of 2000, a mother called Grace to talk with Principal DeeAnn McKay, who had recently succeeded Mary Ellen Hood. After her son freaked out when asked to undress for a physical, a doctor wondered if there was sexual abuse in the child’s past. McKay said she didn’t know of anything. The boy was another one of Aaron’s victims; also late to Prochaska’s class.

Then, in early October, another mother contacted McKay, expressing concern that Aaron was giving her son special attention: an extra birthday cupcake, a kiss on the cheek during gym class to encourage him when he was struggling to finish laps; she also frequently saw Aaron playfully swatting kids on the butt. Then, there was yet another mother who called McKay in October to inform her that Aaron removed three boys from class, walked them toward the edge of Grace’s property, told two of them to stay put, and led a boy named Jason alone into the woods.

Jason’s father figure paid Principal McKay a visit in late October 2000. He wanted her to know that Aaron was planning to host a sleepover for a group of third grade boys after Grace’s annual Hallelujah Party. Plus, earlier that year, Aaron took Jason alone to the movies and back to his house afterward. McKay then talked with Mary Ellen Hood, the previous principal. Hood told her that she instructed Aaron not to be alone with students off-campus. Hood was surprised to learn that Aaron was now disobeying those orders.

After all this, on October 27, 2000, Principal McKay and head administrator John Dunlavey sat Aaron down for a marathon two-and-a-half-hour long meeting. (This was a year before the signing of the “do not fondle” agreement.) Dunlavey explained that good Christians often get falsely accused of things, giving examples of legal cases he learned about in grad school for Christian school administration at Oral Roberts University. Dunlavey and McKay were firm: no being alone with children off-campus (maintain “two-deep leadership” as they called it).

“What if I get invited to a swim party at someone’s house?” Aaron asked. “Only where there would be numerous other adults present,” Dunlavey answered. They instructed Aaron to stop babysitting and inviting students to his home. McKay monitored Aaron’s compliance with the babysitting stipulation by periodically asking him if he was babysitting. Grace ran on the honor system.

There was yet another incident in October of 2000. Zach, a first grader, was on the merry-go-round one day at lunch. Aaron helped him off. Zach made a beeline for his teacher, telling her Aaron had touched his genitals. Aaron assured the teacher it must have been an accident; Zach insisted it was intentional. Later, the teacher called Zach’s dad. He hung up the phone thinking it was an accident. The teacher said she never reported the incident to anyone else—not Grace, not the police.

Zach had done well in kindergarten at Grace, but something changed in first grade. He started getting in trouble at school, especially for sexually acting out—one of the more common indicators a child has been molested. (Yet, some victims don’t have any noticeable behavior change.) Zach suddenly hated school and refused to give his mom, Julie, a reason. “What about PE? You get to run around and play,” Julie asked him. “I hate going to PE,” Zach answered. Until then, Aaron had been Zach’s favorite teacher. He’d been Julie’s favorite too. Aaron seemed like the only teacher at Grace who didn’t look down on them for not living in a $1 million home. In fact, the family could barely afford tuition, which was about $2,000 per year. Then, too, there were the monthly fundraisers students were required to participate in.

Julie met with Principal McKay, telling her Zach wasn’t doing well at Grace, and the financial burden was overwhelming the family. “Have you thought about getting a second job?” McKay asked. Julie explained they’d still be short. “Well you and your husband could both get part-time jobs,” McKay suggested. Both Julie and her husband were working forty-hour weeks already. She told McKay they had an eight-month-old baby at home, a boy they’d never see if they followed her advice. As Julie saw it, McKay only cared about Grace losing their tuition money. Colleagues say McKay was a real go-getter, determined to climb all the way from kindergarten teacher—where she began—to elementary school principal. Like Mary Ellen Hood before her, Grace was McKay’s life. Blonde, always ready with a fake smile, “all plastic” (in the words of a former student), she was one with the institution: “Grace personified,” as one longtime teacher described McKay. To let a family leave the school was to admit Grace was not perfection upon a hill in Broken Arrow. “You should think about what is important to God,” Julie remembers McKay adding.

Julie left the principal’s office bawling. She withdrew Zach from Grace shortly thereafter. It was then that Zach told her, “There’s someone there who is touching kids in their private area.” It was Aaron, and Zach was one of those kids. It is painful for her to think back on it, but Julie didn’t believe her son. Aaron? No way, not in a million years. It is a common misconception that children lie about sexual abuse. In reality, kids rarely ever do. But Julie consulted with her husband, who told her about the teacher’s phone call, and they considered the matter settled. They should have but did not make a report to the authorities—like Grace, except without the whole body of additional knowledge Grace had.

During the whole 2000–2001 school year, Aaron would pop by Grace’s after-school program, help himself to cookies, and ask to borrow a boy.

“May I borrow so and so?” he’d tell the after-school workers, and the boy would go with Aaron and then come back alone an hour later with a piece of candy.

Head administrator Dunlavey and Principal McKay hadn’t told anyone else at Grace that Aaron was not to be alone with boys. At the end of the school year, Aaron decided to have a daycare in his house for Grace boys. This was after he was ordered to stop babysitting. McKay knew about it in advance and did nothing to stop it; Dunlavey found out after the fact. Four boys were molested at Aaron’s home daycare during the summer of 2001.

“I’m glad to hear it,” McKay gushed when another Grace employee remarked that he asked Aaron to serve as a counselor at Camp Dry Gulch, where Grace kids went. This, too, was the summer of 2001. Aaron molested two boys at Camp Dry Gulch.

Josh, Aaron’s first victim, made his parents promise not to tell a soul. They promised. He was in tenth grade. At school, he could not become The Kid Who Got Molested. Together, Josh and his parents drafted the first anonymous letter. Josh had a hunch he wasn’t the only one who’d attempted or considered suicide. “This is a matter of life or death for a child or children,” the letter urged. “We thank God every day that this did not go unrevealed any longer in our son’s life … [He] will not carry this experience and shame into his adult life, as others may.” The letter was signed, “Your Brother & Sister in Christ.”

Addressed to head administrator John Dunlavey, the letter arrived on August 16, 2001 by certified mail. Dunlavey opened it and prayed. “Lord, what do I do with this?”

Dunlavey photocopied the letter and took it straight to Pastor Bob and Associate Pastor Chip Olin. Instead of contacting the authorities, Olin and Pastor Bob went to their lawyers. That consultation did not lead Grace to go to the authorities, either. Instead, they took the law into their own hands, with Dunlavey as their detective.

Grace installed cameras in the hallways. Dunlavey and Principal McKay walked by the gym a little more often than usual, keeping an eye out. Every Tuesday afternoon, during his weekly meeting with Pastor Bob, Dunlavey reported back what he’d seen: a whole lot of nothing. Grace later testified that they interpreted the letter as a generic warning: about what and about whom, they weren’t sure, but they claimed nobody suspected sexual abuse. They latched onto the ending: “Watch, pray, open your eyes, be discreet, and above all use wisdom. God will reveal the truth!”

By October 21, 2001, God had still not revealed the truth. Two days after the “do not fondle” agreement was signed, another anonymous letter arrived at Grace. It was addressed to Ron Palmer, the chief of the Tulsa Police Department, and CC-ed to Pastor Bob and Dunlavey.

“I am obligated by law and by integrity to inform you that I know PERSONALLY that Mr. Aaron Thompson … sexually molested a boy at school.” This, too, was written by Josh’s parents. They were frustrated that nothing seemed to change after their first letter.

Upon the second letter’s arrival, Dunlavey got called into Pastor Bob’s office. Dunlavey asked Pastor Bob what they should do. Pastor Bob said he and Associate Pastor Olin would take care of it. Pastor Bob and Olin then discussed the letter with Dan Beirute, their lawyer at Winters & King, Inc.

Dunlavey and Olin called Aaron in for another meeting and handed him the letter.

“I don’t know what to say,” Aaron told them.

“Some encouraging words would be really good right about now,” said Olin. “Like, ‘I didn’t do this,’ or ‘I’ve never done this before’ and—or ‘that is not me.’ ” Aaron simply nodded in agreement.

It was a short meeting. Dunlavey and Olin reminded Aaron about the guidelines of the Corrective Action Plan, and then he was dismissed.

TPD says they never received the letter. Later, Grace’s lawyer explained to the jury that Pastor Bob and Olin figured they’d be hearing from the police if there was any reason to be concerned.

Dunlavey testified that contacting the authorities on his own prerogative was out of the question: Pastor Bob and Olin called the shots. Dunlavey explained, “I don’t think I would have done it without them okaying it and putting their blessing on it.”

The Arrest (2002)

One Saturday, Lorrie was driving her son Jason, a fourth grader, home from a basketball game. Her cell phone rang. It was Aaron, and he asked to speak to Jason.

“I love you, too,” Jason said to Aaron as he hung up the phone that day.

Lorrie spent the weekend grilling her son about those four words. Jason was defensive and angry. She knew something was not right. Recently, Jason begged her not to have Aaron babysit him. On Monday, they were in the car again, stopped at a stoplight. She asked him flat out: “Has Aaron Thompson ever touched you in your privates?”

Jason answered yes.

On March 12, 2002, Lorrie met with school administrators in Jason’s fourth grade classroom. She told them what Jason told her: Aaron rubbed his genitals in chapel at Grace. Lorrie was beside herself: on the one hand, she didn’t think Jason would lie about something like this; and on the other hand, she—like everyone else—didn’t think Aaron could possibly have done anything of the sort [3] . Lorrie watched the associate pastor, the principal, and the school’s head administrator take it in. She was struck that none of them seemed the least bit surprised.

At the end of the meeting, they prayed together.

Lorrie had mentioned Aaron’s ongoing babysitting of Jason, which meant Aaron violated Grace’s Corrective Action Plan. This required a firm response. But Jason’s molestation allegation was a separate matter—and one Dunlavey and Olin later said they didn’t actually believe. They decided to suspend Aaron. Olin then called Pastor Bob, who was traveling.

Rather than contact DHS or the Tulsa Police Department, Pastor Bob decided to confront Aaron upon his return. Olin made some phone calls—to Grace’s attorneys at Winters & King, Inc.: Dan Beirute and Mike King. The next day, Olin announced that Grace employees were to bring him any and all documents pertaining to Aaron. (Youth pastor Mike Goolsbay, for his part, destroyed a photograph of Aaron.) Olin handed the cache over to the attorneys.

A meeting with Aaron was scheduled for Wednesday, March 20—a full eight days after Lorrie’s confrontation—“in order to allow [him] to hear the allegation,” Dunlavey later wrote in a letter to the International Christian Accrediting Association, detailing Grace’s extra-judicial proceedings. During those intervening eight days, Dunlavey said, “All I did was pray.”

Wednesday came around. Associate Pastor Chip Olin, head administrator John Dunlavey, attorney Dan Beirute, and Pastor Bob met with Aaron in the church’s conference room. Olin told Aaron that they received a molestation report from a parent. Olin asked if it was true. There was a long pause. Finally, Aaron answered yes. They asked if there were others, and Aaron named two additional boys. Olin beseeched Aaron to report himself to the police. Aaron hesitated, so Olin called a Grace congregant who was a police officer. Then, another TPD child abuse detective called back.

At the end of the meeting, Olin, Dunlavey, and Beirute had Aaron call DHS to report himself. Pastor Bob had already left the room by this point.

“I think he had other responsibilities,” Olin testified.

TPD arrested Aaron on March 25, 2002. Five days later, Pastor Bob wrote an open letter to the Grace community.

“That such behavior may have occurred and caused injury to children is unthinkable,” he noted. “Pray for the children and the families directly affected, especially for the children.”

Pastor Bob’s next letter to parents on April 5 began with an apology. “The time required to focus on these events has made it difficult to communicate with those who matter to me most—you and your family.” Pastor Bob encouraged parents to be in touch. By proxy. “I have directed Chip Olin, Associate Pastor, with responding to you directly,” wrote Pastor Bob. He assured the parents that Grace was “aggressively developing community resources that will give us guidance to ensure that this never again happens at our school.” But, when Dunlavey and McKay testified nearly two years later, they said no changes had been made to Grace’s child abuse reporting policies since then.

It should be noted that Dunlavey, along with Principals Hood and McKay, had certificates of completion from “Child Lures,” a popular national sex abuse prevention program offered in conjunction with their law firm, Winters & King, Inc. At public schools in Oklahoma, staff are required to undergo yearly training on recognizing and reporting child abuse and neglect.

After the Arrest

Over a lifetime, the monetary costs of caring for a sex-abuse victim can be sky high. Clergy sex abuse victims generally expect settlements of about a million dollars apiece. In lawsuits against the Catholic Church, attorney fees ate up about 40 percent of the settlements. In 2003, Aaron pleaded guilty to molesting nine boys between 1996 and 2002—sixteen counts of lewd molestation and two counts of sexual abuse of a minor. (Aaron’s 25 year sentence ends in 2027, but he’s up for parole in 2023.) Long after Aaron’s plea agreement, a 10th and 11th boy came forward and successfully sued Grace for negligence. If Grace’s settlements approximated those of Catholic churches, the Aaron Thompson ordeal could’ve cost them about $11 million, not including the defense’s attorney fees.

In the aftermath of Aaron’s arrest, faced with a spate of costly negligence lawsuits, Pastor Bob circled the wagons. In 2002, on the advice of their law firm Winters & King, Inc., Grace moved all of their assets into a dummy corporation. A $7.5 million mortgage, $1.2 million in cash, all of Grace’s furniture and equipment—everything went into Grace Fellowship Title Holding Corporation. In a letter to Bank of the West, Grace board member and Financial Director John Ransdell explained that the board approved the corporate restructuring in hopes of “protecting the assets of the church in the event of a catastrophic event in the school that resulted in a momentary award exceeding insurance coverage.” Ransdell is currently the president of Grace’s Covenant Federal Credit Union, a position he’s held since 1993.

In court filings, plaintiffs’ lawyers alleged Grace committed fraudulent conveyance, which is a civil offense. All the Grace lawsuits were settled before reaching the stage at which a court might have awarded damages for fraudulent conveyance. Several plaintiffs’ lawyers told me Grace’s financial maneuverings didn’t impact their settlements. But it’s the thought that counts. As attorney Clark Phipps explained, it “rubbed salt in the wounds” of the victims and their families.

Plaintiffs’ lawyer Laurie Phillips remembered it took forever to assemble a jury for John Does 1–7 versus Grace. Potential jurists kept getting disqualified. As Phillips put it dryly, “Everybody in Tulsa has been molested in Tulsa County— or has a sister or a brother or a child who was.” Each year, Oklahoma DHS has about 1,700 confirmed cases of child sex abuse, with underreporting a given.

After a grueling seven-week trial, in October 2004 the jury found that Grace acted in “reckless disregard” and awarded the seven John Does a total of $845,000. The individual amounts ranged from $75,000 to $250,000. It was a pittance, given that each boy paid about $60,000 in lawyer fees that came out of their settlements. The jury found that Pastor Bob, Associate Pastor Chip Olin, head administrator John Dunlavey, Principal DeeAnn McKay, and former Principal Mary Ellen Hood acted negligently. (According to plaintiffs’ lawyers, Mike Goolsbay was not a defendant in the trial because his role with the lewd emails didn’t come out until late in the discovery process. Goolsbay was named in two subsequent lawsuits.) “Reckless disregard” meant the jury could have awarded punitive damages in the next stage of the trial, but the lawyers settled out of court for an undisclosed amount before then. The court had capped the possible punitive damages amount at $870,000, so it’s a fair bet that the plaintiffs settled for less than that.

Seven boys, less than $2 million in settlements. Grace got off cheap, especially considering that, as one boy’s mother told the Tulsa World, the school “turned and looked the other way and protected their reputation and not my son.” Grace’s new children’s building almost certainly cost far more than the settlement.

On the Sunday after the settlement, Prochaska and the anonymous “Special T” said Pastor Bob announced the news to the congregation. Prochaska remembered punch and cookies at the end of church services; the anonymous “Special T” remembered a song with a pointed chorus: “freedom, freedom.” Thinking back to that Sunday, Prochaska’s colleague reflected, “Pastor Bob had the whole church rejoicing over them being free of [the lawsuit]—not praying for the families.” Several victims’ families confirmed that Pastor Bob never offered them an apology.

Josh’s Lawsuit

Josh and his family didn’t want to sue. (Josh testified in the John Does 1–7 trial but wasn’t one of the 1–7.) But, with his statute of limitations about to expire on his 19th birthday, Josh filed an extension protecting his right to sue—just in case. Sure enough, shortly thereafter, Grace stopped paying for his therapy.

Josh wanted something that Grace—as a corporate entity deeply vested in protecting its assets—would never give him: an apology; a recognition that he’d been wronged and hurt; an assurance that the people in charge were sorry for failing him. A court could tell him what Grace would not: the school hadn’t protected him when they could have and should have. “If Bob had been kind and repentant and just a little heartbroken,” Josh reflects, “I would have never sued Grace.”

In February 2005, during the discovery period of the suit, Pastor Bob and his lawyer submitted a request for admission that tried to get Josh to “admit that you touched Aaron Thompson in a sexual manner before he first touched you in a sexual manner.” Josh was 11 when the abuse started.

Grace also subpoenaed his therapist’s notes, apparently trawling for material that would help make the case that Josh somehow seduced Aaron as a fifth grader. After that, Josh could no longer trust the very person who was supposed to help him heal. He was just starting to get to the place where he didn’t think the abuse was his fault. But that set him back. Way back.

While Pastor Bob engaged in victim blaming, surprisingly, no one at Grace retroactively labeled Aaron a gay child molester. This was remarkable for a deeply conservative mega church that offered “Restoration by Grace,” an in-house pray-away-the-gay counseling program.

Josh’s entire middle school and teen years were taken up with his abuse—first with the molestation itself, and then with the criminal case against Aaron and the lawsuits and the endless depositions and hearings. It all blended together. The subpoenas were never-ending. He was forced to live it again and again and again. He said what many sexual assault survivors say: the protracted agony of the legal system was yet another assault. During one deposition, as he talked he could see his mom through a window in the door. She was sobbing.

After Aaron’s arrest, Josh defected from Grace and spent the remainder of high school in homeschooling. Reading on his own, learning about things like evolution, he marveled at the realization that Bible class, science class, and history class were pretty much interchangeable at Grace. Slowly, he began to cast off his biblical worldview. The only direct Grace contact Josh had was with John Dunlavey, who was always apologetic and kind when they ran into each other. So Josh was surprised when Pastor Bob’s lawyers contacted him with a message: Pastor Bob wanted to discuss a settlement with him over lunch at Marie Callender’s, a home-style chain restaurant.

Josh thought Pastor Bob wanted to say he was sorry for what had happened. He also thought Pastor Bob was taking him to lunch. But it soon became clear that Josh was paying his own way, and Pastor Bob was not there to apologize. Josh ordered a glass of water and watched Pastor Bob eat.

“He quoted scriptures about how I was sinning against God for coming against his church, his ministry,” Josh remembers. But Josh came prepared with scripture passages of his own, about the responsibility of a shepherd to protect his flock. The message fell on deaf ears. Josh drank his water. Pastor Bob ate a big meal and ordered dessert.

The School Closes

In the year after Aaron’s arrest, Grace saw an exodus of students who headed for other Christian schools attached to Tulsa area mega churches, like Victory Christian Center or Church on the Move. But before long, enrollment stabilized, more or less. Then the economy went bad. At the end of the 2008–2009 school year, Grace had 300 kids in grades K–12. The previous year it was 400.

In May 2009, Pastor Bob announced he was closing the high school. Nineteen employees lost their jobs. everyone hoped it would be temporary—as soon as the economy got back on track. But in July 2010, Grace announced it was closing the elementary school, too. After 32 years in operation, the church was losing too much money on the school.

Josh’s mother broke the news. “Good riddance,” he texted back.

The Long Arm of Grace

Jeff and Lynn wanted to send their son Gabe to a good Christian school. Gabe had always been an easygoing kid. But somewhere around first or second grade at Grace, he changed. Lynn would pick him up in the afternoon, and Gabe would beat on the dashboard, saying he hated school and didn’t want to go back. He started acting out. Over the years, just about every counselor or doctor who looked at Gabe told his parents he had all the hallmarks of sexual abuse in his past. Jeff and Lynn guessed Gabe was in denial. Of course, they didn’t realize Gabe was one of the boys who were late to Laura Prochaska’s computers class.

“My son just got out of jail again,” Jeff begins to tell me over the phone, his voice weary. “He got home and lasted two days before he was back on drugs.” Jeff and Lynn are the kind of people who strive to keep their driving records spotless.

Once, Gabe threatened to slit his parents’ throats.

“That night I found a box blade under his mattress,” Jeff remembers. “At that point in life it didn’t surprise me. We had been down the path with him so much. We were living with 30 or 40 holes in our walls from him kicking them in.” To say Gabe was angry was an understatement.

One year shortly before Christmas, Jeff and Lynn were on yet another psych ward with Gabe. Something snapped, and Gabe threw a chair at a plate glass window, aiming for his mother. On Christmas Day, calling from another in-patient facility, Gabe finally broke down and admitted it.

“Mom,” he said, “something did happen at Grace.”

The stipulations of the settlement don’t allow Jeff to name dollar figures, but he says it doesn’t even begin to cover the cost of rehabs and detoxes and psych wards and halfway houses. A weekend on a psychiatric unit costs $12,000. Jeff and Lynn have paid Gabe’s medical bills instead of putting away money for their retirement. Besides Gabe, several of Aaron’s other victims have required in-patient treatment of one kind or another.

A lifetime ago, Jeff and Lynn had an account in Grace’s Covenant Federal Credit Union. That was just the culture. “You’re one for all and all for one, and you’re trying to help each other,” Jeff explains. “Why not keep it in the family?”

At some point in the phone call, Lynn comes home. She tells Jeff she brought some groceries over to Gabe that day. Gabe’s doing well, for now at least, which is all they can hope for. During those times when she’s scared of their son, or if Gabe’s lashing out and calling her names, or if he’s in one of his explosive rages, Jeff tells Lynn to not answer the phone: he’ll deal with Gabe. But, Jeff explains, she always caves in, wanting to help. His voice becomes soft. I get the feeling Lynn is standing nearby—that Jeff is talking to her now. “She’s so tender, and so loving.”

In November, Jeff and Lynn renewed their wedding vows and went on a second honeymoon to Hawaii. They love their son, they will be there for him, but now the next chapter of their lives is beginning. “He’s part of life, but he’s not all of life,” Jeff says, determined to make this a reality.

Gabe met his girlfriend in rehab. Last year, Jeff and Lynn helped the couple get set up in an apartment, assembled donated furniture from friends, and paid for the first three months rent. Two weeks after moving in, Gabe was in police custody again: a domestic assault against his girlfriend. They’re still together. In March, she gave birth to their son. Then, Gabe returned to jail, serving his sentence for last year’s assault charge; mother and child just checked into court-ordered rehab and can’t see visitors for a month. “Kinda takes the fun out of being a grandparent,” Jeff wrote in an email shortly before this story went to press.

Julie and her husband were not fated to have a second honeymoon. Who is to say what ends a marriage, but the life Julie and her husband had together for 14 years could only withstand so much. The pressures of the aftermath of Zach’s molestation were not among the things they could bear—together, at least. Trusting one’s own had been a basic fact of everyday life. Suddenly, everything they took for granted in this world was upended. Abuse is experienced by entire families, and it goes on long after the physical part is over. In the wake of Aaron’s arrest, for the parents of the victims, at least two other marriages broke up.

It took Julie nearly a decade to be among Christians again, to conceive of church as a place where healing might be found. “I lost faith in people,” Julie says. “I didn’t lose faith in God.”

If Gabe is one end of the sexual abuse spectrum, Josh is at the other. Of the two paths, child abuse experts say Gabe’s is probably more common. The deck is stacked against abuse victims.

In his teens, Josh was angry: at Grace, Christianity, his parents, everything and everyone—but especially at Aaron and Pastor Bob. “I used to dream of beating Aaron and Bob with baseball bats,” Josh remembers.

After settling his lawsuit, around the time he turned 20, a realization set in. All that bitterness wasn’t making him the person he wanted to be. So he hit the road, crisscrossing the country, ending up at the 2006 Austin City Limits music festival. It was there that he got a tattoo across the underside of his left forearm: Hebrew letters that spell out “mechilah”— forgiveness. Forgiveness was what Josh wanted: not the Christian concept of forgiveness, but more a state of mind—of being at peace with the past.

Forgiveness was a goal, not an immediate reality. Josh returned to Tulsa and made a second suicide attempt. He swallowed two bottles of Tylenol PM and woke up in a hospital bed. “All my family and friends were huddled around me,” Josh says. “I was so embarrassed and disappointed that I was still there.” He spent the next few weeks on the psychiatric ward, wishing he’d been successful.

By the time he got the tattoo, life had settled down enough for him to mourn just how much of it he’d missed. 1996 to 2006 was Josh’s lost decade. He was a little kid, and then, suddenly, he was an adult. Growing up, growing into one’s own as a sexual being—Josh had been denied these things. “I couldn’t imagine a future without something terrible happening to me.”

In the years that followed, Josh worked at letting go. There on his arm, he bore mechilah, a daily reminder. That’s what he wanted, especially for himself—for “letting it happen to me,” as Josh puts it.

“For a long time I had the mentality of ‘I am a child abuse victim,’ ” Josh says. “Now I have other things. It’s not something that defines me like it once did.”

At 27, Josh is ready to leave Tulsa. He has always felt years behind everyone else his age. But he’s catching up. He was just accepted to a prestigious art school. He’ll enroll in the fall. Meanwhile, Josh works a dayjob and makes art. That’s what got him through his teens and into his twenties, and that’s what will take him to whatever comes next.

***

Dick Thompson, Aaron’s father, and I emailed back and forth for some time. I wanted to visit Aaron at the Joseph Harp Correctional Center, where he is said to have a thriving prison ministry. The Thompsons were deciding as a family whether they wanted to risk “going public” with their experiences. Christmas 2011 turned into the New Year. There was a much apologized for lull while the Thompsons remodeled their house. Then, I got this email:

Aaron took a situation that could have destroyed him, but with God’s help has received healing, rehabilitated himself, and moved on accepting responsibility and consequences for what he did. Our prayer is that all of the alleged victims have also received healing and moved on with their lives. However, we know that may not be true for all of them. Those who are stuck in the past and resisted God’s healing and forgiveness will continue to blame Aaron and others for whatever failures they have in their lives. Being fondled or molested as a child, is a very bad thing, but many, many people who have gone through that have grown up to be very successful individuals and even role models for others, so it is not an experience that cannot be overcome. As with all things that happen in our lives, it’s not what happens to us but how we respond that makes or breaks us and/ or reveals our true character.

It turned out that Josh did not resent Dick Thompson’s characterization of the long-term effects of abuse as personal failings on the part of the victims.

“Parents always want to see the best in their children,” Josh replied. He was calm. I was baffled.

“You’re not angry?” I asked.

“I guess I’m just all out of anger,” he said.

Pastor Bob’s Practical Wisdom

Photos of Corvettes are displayed on the bookshelf in Pastor Bob’s office. One day shortly before Thanksgiving, Pastor Bob welcomed me into his domain. He held forth behind his big wooden desk, wearing jeans and a gray wool pullover that clung to his belly.

“We trusted this kid,” Pastor Bob told me. “I’m not omniscient—I’m not like God,” he said. “The church is just people.”

Up close, Pastor Bob’s skin had a purplish putty quality. His bulbous pug nose was a few shades darker than the rest of his face. Pastor Bob continued, “You never quit trusting people. You just get wiser through the years.”

Soon, our conversation turned to Penn State, which had recently been cast into the national spotlight over what appeared to be a child sex abuse cover-up. Pastor Bob hoped there were Believers on staff there to guide the university through the dark times to come. He identified with the school’s predicament, he said, for he too was once accused of turning a blind eye at Grace. He remembered the parents of the victims were particularly accusatory. “When we found out, we fired [Aaron] and called the police,” Pastor Bob said. “But it’s never early enough with them.”

Every day during the seven-week John Does 1–7 versus Grace trial, Pastor Bob’s wife, Loretta, made him a list of scripture to read. He drew spiritual strength from the Psalms on deliverance and protection, especially Psalm 91. “He’ll protect you from arrow by day, the terror by night, the snare of the fowler,” Pastor Bob recited, his own condensed version. When the jury came back with the verdict, Pastor Bob marveled at the low amount Grace had to pay the victims.

Before long, Grace got back to business as usual, as Pastor Bob always knew they would. He leaned forward slightly and bridged his hands. “Many are the afflictions of the righteous, but the lord brings you through all of them,” Pastor Bob said. “So we came through.”

Today, Pastor Bob estimated 50 or 60 percent of the congregation was unaware of what took place at Grace a decade ago. “The Lord moves on. He promises you that,” Pastor Bob reflected, smiling broadly now. “The ability to forgive and forget is—” Here he paused. “Divine.”

My time with Pastor Bob was up. On the way out, his secretary, Gwen Olin—Associate Pastor Chip Olin’s widow—wished me a blessed day.

***

Back when the lawsuits were underway, Principal DeeAnn McKay was working toward her doctorate in Christian educational administration at Oral Roberts University. Associate Pastor Chip Olin died of cancer in 2007. Now retired, former Principal Mary Ellen Hood lives in Jenks. Since 2007, former head administrator John Dunlavey has been the principal of a private Christian school in South Korea. Dunlavey declined interview requests, saying he wanted others to learn from Grace’s ordeal but was worried his words would be “taken out of context.”

Mike Goolsbay, Grace’s former youth pastor, has his own congregation now, Destiny, a massive stadium of a church with the motto “Loving People.” By car, Destiny is about three miles northeast of Grace, a stone’s throw as distances go in Broken Arrow. Goolsbay still refers to Pastor Bob as “my pastor.” For financial guidance, Destiny’s website recommends John Ransdell, the one who was tasked with maneuvering Grace’s assets into the dummy corporation. Like Grace, Destiny is represented by Winters & King, Inc.

I asked attorney Mike King how he would hypothetically advise Destiny Church if they were to receive an anonymous letter exactly like the first one Josh’s parents sent to Grace. King gave a little chuckle, answering, “Well, it would depend upon the facts and circumstances.”

If anything, the lesson of Grace should be that it never depends.

Just before Thanksgiving, I went to Destiny’s Saturday night church service. On stage, Goolsbay sat comfortably on a stool, against a backdrop of neon blue paneling and jumbotrons. A far cry from Pastor Bob’s formal pulpit manner, Goolsbay ran his service like a call-in radio show, his speech peppered with “dude” and “sweet” and the occasional “ridonkulous.” He videochatted a housebound congregant set to soft keyboard music; played for laughs with a call to his wife to see if she found his lost wallet; and gave a sermon in what he calls his “Perils of Power” series. The message: Accountability begins at home, top-down, from parents to children. King David must hold his son Ammon accountable for raping his daughter Tamar. Leaders went unmentioned.

* * *

Former parishioners say Grace’s heyday was over three decades ago, at the old church building out on Memorial Drive, a few miles west of the citadel on Garnett Road, in the building that was later sold to Higher Dimensions church (where its pastor, Carlton Pearson, stopped believing in hell and all hell broke loose). It was standing-room only back then, with people crammed on a balcony that was really just a half story. That was the heyday of the Word movement, too, when a mega pastor could take to the pulpit and bring the house down and that’s all anybody expected from him.

“Now people want somebody a little more personable,” explains a former Grace member who’d been deeply rooted in the church for decades. Others were less charitable in their assessments of Pastor Bob: “no emotion” and “nothing behind the eyes.” Tulsa, of course, is a city with ever-multiplying church options.

On Sundays, Grace’s parking lot is typically half full, if that. The church still offers a kids program, but attendance has dwindled. Peek into the children’s building on a Sunday, and you’ll find more building than children. Grace’s membership appears to skew older, now, toward the retiree set. In the sanctuary/former gym, the big, padded seats are spread further apart, masking the emptiness. Basketball hoops are folded against the ceiling. The gym floor is still emblazoned with a maroon and gray decal of a basketball with the lettering “Grace Christian eagles,” a relic from another time.

Recently, Grace board members gave Pastor Bob a list of thirty things he could do to be more “people friendly.”

“Why aren’t things like they used to be?” he asked them. He was genuinely puzzled.

The Sunday before Rick Santorum won the Oklahoma primary on Super Tuesday, the former Pennsylvania Senator made a single campaign stop in Tulsa. Santorum spoke from the pulpit of Grace’s gym/sanctuary, where he denounced liberals for thinking “the elite should decide what’s best for those in flyover country.” The crowd cheered and waved their Santorum placards, the word “COURAGE” projected upon the jumbotrons that flank the stage. It was a packed house.

Back in the day, Pastor Bob would say he’d preach ’til he died. But those close to the church board say he’s announced he wants to step down soon. His son, Pastor Robb Yandian, will ascend the pulpit. Aaron has 15 more years to serve on his sentence. The boys are now men.

Grace never built the auditorium they’d planned, the one that would have connected the children’s building with the main wing. They constructed what was to be the connecting wall of the children’s building out of material that wasn’t weatherproof, leaving it vulnerable to the elements. There are leakage problems now. There is also talk of perhaps selling the land in front of Garnett Road just to make ends meet. Then again, maybe things aren’t so bad: Grace had a budget of nearly $5 million last year and ended 2011 in the black.

Heading toward the Mingo Valley expressway on the way out of Broken Arrow, you can see, rising from the hillside, something that looks like a brand new airport hotel. It’s stamped with rainbow-colored lettering large enough for passing cars along east 91st Street to read from across an immense grassy field: “Grace Kids.”

Inside, a gilded carousel awaits.

Timeline:

1972: Bob Yandian is among the 52 founding members of Grace Church

1973: Bob Yandian begins working for Kenneth Hagin Ministries. Hagin, a televangelist, plays key role in popularizing the prosperity gospel.

1977: Bob Yandian begins teaching at Hagin’s RHEMA Bible Training Center, eventually becoming Dean of Instructors

1979: Michele Bachmann begins law school at Oral Roberts University and is study buddies with Mike King (who later becomes Grace’s lawyer)

1980: Bob Yandian—“Pastor Bob”—becomes pastor at Grace

1990s: Regular visitors at Grace include Sen. Jim Inhofe, Rep. Steve Largent, and Sen. Don Nickles—members of the powerful evangelical group known as the Family

1993: Pastor Bob publishes One Flesh: God’s Gift of Passion–Love, Sex & Romance in Marriage, a hugely popular Christian advice book (blurbed by Oral Roberts)

1995-1996 school year: Aaron volunteers as Grace’s assistant basketball coach/assistant youth pastor under Mike Goolsbay. Aaron answers “no” on application form when asked if sexually abused as a child

1995-2001: Gabe attends Grace Kindergarten-4th grade (molestation occurs around 1st or 2nd grade)

1996: Aaron sends lewd emails to a boy on the basketball team. The father complains to Goolsbay, who promises to put the emails in Aaron’s permanent file. They are never found.

1996-1998: Aaron sexually abuses Josh, a fifth grader at the start. Josh makes his first suicide attempt.

1997: Grace hires Aaron as part-time assistant athletic director

1998: On Mike Goolsbay’s recommendation, Grace hires Aaron as full-time PE teacher

1998: Teacher Laura Prochaska begins noticing that certain boys coming from PE are repeatedly late to class and sullen (Aaron’s victims, they later learn). She tells Principal Mary Ellen Hood but sees no apparent follow-up.

1999: Aaron graduates from Oral Roberts University with a degree in accounting

1999-2000 school year: Principal Mary Ellen Hood and head administrator John Dunlavey tell Aaron he can’t be alone with children off-campus after a father complains Aaron had showed up at their house wanting to treat his son to lunch. The boy was regularly late to Prochaska’s class

Summer 2000 or 2001: Aaron tells Goolsbay that he was molested as a child (meaning he lied on Grace’s volunteer application form)

September 2000: John Doe #7 moves away from Tulsa. His mother calls Principal DeeAnn McKay to ask if there’s sexual abuse in his past after a doctor inquired. McKay says she doesn’t know of anything. (The boy had been late to Prochaska’s class.)