Somebody has to drive Mike Samara to work every night, and Suell Turner figures it might as well be him. “If you can’t help somebody at this age,” he said, “you’re not worth anything.”

Turner’s been coming to the Celebrity for as long as he can remember. Samara has been coming since 1963, the year he bought the place. Before the Celebrity Club was a steak house it was a bar called the Celebrity Club. It’s now, in theory, the Celebrity Restaurant, but in practice nobody calls it that. The club-restaurant confusion is the holdout of an era of grand eating and drinking that occurred inside candlelit rooms without televised sports or war news flashing on multiple screens. It also refers to the period of liquor by the drink, which those who were there called “liquor by the wink,” a reference to the flaunting of teething, if not toothless, state drinking laws by prince and pauper alike.

God damn, they’ll say, those were the days.

If you were lucky enough to have seen Samara in action before his eyes went, the tales you could tell. The man was one heavenly host, with manners and moves as warm and smooth as butter you left out overnight. Now, in the darkness that blindness serves up, Samara must work by second sight. Which he does, after five decades of practice, supernaturally.

A few minutes of six, with Joe Adwon on the way and my martini still cool, a woman walked into the club, the restaurant, and made her way toward the bar. Along the way, she overtook Samara, who was making his way back from his office. He shuffled slowly, feeling his way. As she passed, our eyes met briefly. Hers darted without acknowledgment toward a table in the dining room with her name on it, and mine as quickly back to the man in glasses who can’t see six inches in front of his face.

As she glided past him without a word, Samara cocked his head slightly back and reached one hand out into the airspace she’d freshly vacated. I could only guess at what he’d sensed: a perfume trail, a small breeze, the light slap of a heel rising and falling inside its backless pump? It was as if a ghost walked by, and maybe she did. For what are ghosts but walking embodiments of things past?

When he got close enough to touch, I put my hand on his shoulder. “Hey, Mike,” I said, kind of loudly, because that’s going too. “Hi, Mark,” he said. “Can I offer you something to drink?”

For reasons reasonable and resolute, people don’t eat steak like they used to. “This place used to be so busy,” Turner said. “They’d cue up from that front door to the end of that bar, two deep, six nights a week.”

Things, Turner said, are not like they used to be.The economy’s different,for starters,but so are the big spenders. Families are more insular now and there’s less fraternizing than in the decades gone. And there are more Outbacks.

A restaurant that lives to be 50 should reveal secrets of some kind, not only to restaurants trying to make a go, but also to the meat-and-potatoes culture at large.

“That was back when Tulsa had a whole lot of characters. There were colorful people. We used to all know everybody in town.”

A restaurant that lives to be 50 should reveal secrets of some kind, not only to restaurants trying to make a go, but also to the meat-and-potatoes culture at large. But the Celebrity has a knack of locking away its secrets. It’s a square gray building sitting on a grim intersection in a part of town that most Tulsans navigate en route to elsewhere.

“Everybody overlooks it,” said Adwon, who showed up at six on the dot. “The younger people do not come here.”

The Celebrity is a cave for old bats, stray cats, and night owls. There is one window in the place, and it’s in the kitchen. In the parking lot after dinner, I watched two men at work through the 2-by-3-foot hole offering a view of the dumpster.

“It just happened that there were no windows,” Samara said. “But we had a lot of rumors circulating—all of them false—that I was connected.”

Over the years, Samara has heard many a conspiracy theory. He takes them with a grain of salt and sprinkling of fresh-cracked black pepper.

“It’s ingrained in some people,” he said, eyes aimed just below my chin, “that I’m never telling the truth.”

***

Sailing through 31st and Yale one evening, I looked over and saw Steve Ripley and his wife going into the Celebrity. Ripley’s band, The Tractors, whose debut album went platinum faster than any other country album, produced three albums on Arista Nashville before being cut from the label. I happened to be at The Church Studio visiting a musician friend the day they got the news. Ripley, who owned the Church then, walked by kind of mopey and asked to see my business card. When he walked off, my friend Mark said, “They lost their label today.” The Tractors followed up their hugely successful debut with a Christmas album called Have Yourself a Tractors Christmas. Any pop music act can produce a Christmas single, but it takes a bankable entity to justify a whole album. All the same, I suspect we’ll never see an 8-by-10 glossy of Mike Samara posing with Steve Ripley on the paneled walls of the Celebrity, which is a shame. There’s a perfect spot right between Tim Conway and David Cook.

***

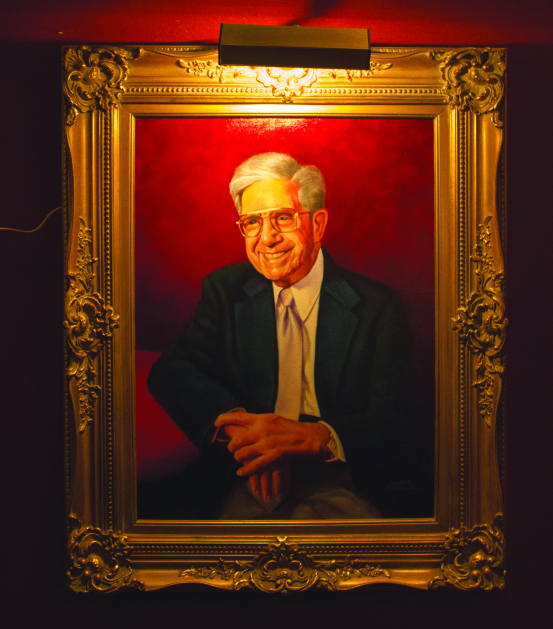

Celebrities flocked to the Celebrity Club probably by osmosis, and some of their moments are captured in photos framed, tacked, and tilting on the paneled walls that talk: “Best wishes and thanks for a wonderful two years in Joplin,” says one signed by Mickey Mantle, with bigger loops in the two Ms than those Sharpeed on the back of my 1969 Topps baseball card, which I sold in a sophomore slump to make rent.

In 1957, at the height of his Yankee career, Mantle became president of the Mickey Mantle Motel Corporation, with H.D Youngman, Mantle’s handler, as vice president. They hired Samara to go to Joplin and run their Holiday Inn.

“My brother was in the club business in Oklahoma City,” Samara said. “He had The Jamboree. I was managing it for him when Mickey and Youngman, his benefactor from Baxter Springs, Kansas, started coming in there.

“I say, ‘Hey, wait a minute, I don’t know anything about a hotel, or a motel.’ And they said, ‘Neither do we.’”

The Mickey Mantle Motel Corporation was building the 50th Holiday Inn in America. They were all at a Holiday Inn party being thrown for new franchisees when Kemmons Wilson, who started the hotel chain in Memphis, took Samara aside and advised him, in a real Southern accent, “Young man, we’re gonna go public!” Samara thought he was being hustled. The Mantle Holiday Inn, like Mantle and Holiday Inn, enjoyed a long, illustrious career. It was torn down, Samara said, before the tornado could get to it. Samara calls it “another era.”

“But that’s what brought me to Tulsa. My brother called me from Oklahoma City in ’59 to tell me that Oklahoma had voted legal liquor in package stores.”

Mantle’s bouts with vodka tonics are as legendary, if not as godly, as his knee-bending at bats with the New York Yankees, the only major league team he suited up for. The 1995 Yankees played two months in black armbands after Mantle died that August in spite of a liver transplant.

A name like Mantle will outlast a man. Until June 2012, fans got their fill at Mickey Mantle’s Restaurant off Central Park South. Still, you can eat a steak and drink a $200 Charles Smith King Coal cabernet-syrah blend at Mickey Mantle’s Steakhouse in Oklahoma City’s Bricktown. “An Oklahoma Legend,” says the website, “Mickey Mantle’s is recognized as Oklahoma City’s top spot frequented by celebrities, athletes, the business crowd, and stylish locals.”

***

In his father’s house are many rooms.

“While Dad was doing the Hilton and the Copa, which was the coolest place on the planet, I managed Big Mike’s,” said Nick Samara, showing me a stack of old photos framing stainless ovens and red-plush booths. “Dad’s always done state of the art.”

Before the Celebrity, Mike had a pizza place and a liquor store next door, Stadium Liquor, on 11th Street across from the college. In the first days of disco, he opened the Copa Room in the Hilton, now Tulsa’s Select Hotel. He opened the first Burger Kings in town, six of them. Before that, it was Big Mike’s Hamburger Palace in the Southland Shopping Center. Southland predated the Promenade, and had its heyday in the 1970s, when 41st and Yale could still be called south.

Big Mike’s sold 55-cent chili and 30-cent shakes. Ad agency fonts and tri-folded design paint the menu in an old-timey light, with the ABCs of “How To Order” posted front and center:

“A. Make selection from menu

“B. Lift receiver and order

“C. When light comes on and buzzer sounds, your order is ready to be picked up!”

I don’t remember eating at Big Mike’s, but I must have. I’d like to think I ordered the Number 10, a “Giant Hik’ry Smoked Frank open-hearth broiled with Western sauce,” and a side of deep-fried Bermuda onion rings.

“Dad did everything first-class,” Nick said.

And most of it, curiously, along Yale Avenue: 3109 (Celebrity), Skelly Drive (Copa), and 4107 (Big Mike’s). Nick was more of a Sheridan man, opening Pepper’s (with partners) on 61st Street and before that Le Café at 36th. Le Café was, of all things, a creperie—a concept not so much ahead of its time as beyond it. Chicken a la reine, ratatouille, stroganoff burger, and his-and-her corned beef and cheese sandwiches: the Reuben and the Rachel.

“Le Café, on 36th and—” Nick started saying.

“Pasta Pete?” Mike asked.

“Oh, no that was… remember the crepe place?”

“Oh, yeah, Le Café!” said Mike, reclining in his chair.

“I still owe you 5,000 bucks from that,” Nick said. “I’ll pay you back.”

***

A pair of dwarf pines greets you at the door, at the end of a worn, red carpet runner. A strand of red Christmas lights offers the gray stucco façade its only relief. This would be the area where people who congregate outside restaurants to smoke would usually stand, but something about the Celebrity discourages this. Possibly the traffic, which you could reach out and kick so close is it. Across the street, the “O” had gone out in the neon sign of Cloud 9 Gentlemen’s Club, leaving silhouetted sirens straddling poles to fill in the blanks.

The front door of the Celebrity once led to a liquor stand, a tiny mom-and-pop that sat symbiotically to the place when it was a bar. In its current incarnation, the Celebrity bar is something of a keyhole itself, the Acheron you must pass on your way to the dining room.

The bar top is padded, for the leaning-and-drinking sort. It took all my powers to keep a fishbowl martini in its rim, lifting it up and over the cushion like a dose of liquid nitro. I made a note to stop after one. Between sips, I stared at an episode of God, Guns & Automobiles. The sound on the television was muted, and for a minute I tried following the dialogue in the closed captions. Then I quit reading but kept watching to see if I could pick the God parts out from the others. “We can change it,” the bartender said. I told her to leave it, that I was waiting on somebody, and would soon be moving to a table.

A Dow ticker scooted across the bottom of the screen and I wondered if the fortunes of the Celebrity rose and fell with the market, or if it were grandfathered against such trends. Above me, the bowls of a hundred wine goblets, brandy snifters and champagne flutes shone like hollow stars.

***

My dad told me never to open a restaurant unless I wanted to end up living there. Watching all-but-blind Mike Samara navigate his restaurant by feel pretty much proves that point.

“He had a little vision up to about two years ago,” Nick said. “His outside peripheral was the last thing that would really let him know.”

Now, Turner is his eyes, the McMahon to Samara’s Carson, reading the crowd and taking cues. Suell Turner provides relief to Nick and Paula, Mike’s daughter. “Suell is his sidekick,” Nick said, “his master of ceremonies. He’s a good man. He’s doing his penance.”

Turner, a retired independent oilman, developed a taste for margaritas in a past life and was thrown out of the Celebrity a handful of times. Some of those times, he’d sneak back in through the kitchen and reclaim his place at the bar. It’s been four years since the 83-yearold Turner had a margarita, or any other drink. Chauffeuring Samara does them both some good.

“I miss the freedom—freedom from dependency,” Mike said. “One thing, though, I always have company.”

One night at the Celebrity, I closed my eyes for a few seconds, just to see. I smelled the inescapable aroma of broiled meat. I jumped at the howls of a pack of laughing girls-night-outers. I felt the coolness of my martini and sipped too large a sip. I felt it spill a little down the side of the glass. I heard Nick say, “How we doing?” and heard a guy say back, “37,” and Nick say, “Not bad.” After a few seconds, I opened my eyes and it was like being in a country pasture on a starry night.

Whenever Samara shakes hands, he’s first to draw. You always take his hand, which dangles out in front of him about chest high. His hand is warm and soft as mashed potatoes. “If I could see my hand it would help,” he said. “But there’s no light. Just a solid black.”

***

One place Samara always loved was “21” Club, the New York legend so named for its 21 West 52nd Street address. It was the 42 Club, at 42 West 49th, until Jack Kriendler and Charlie Berns moved it to make way for Rockefeller Center.

In 1976, Samara was about to open a new restaurant at the top of the Utica Bank Building. But, he didn’t know what to call it. “We kept getting suggestions. Everything was about Swan Lake, Swan Lake. ‘Swan Club.’ One day I was driving in—we were still under construction—and I turned off 21st onto Utica and I said, ‘That’s it! That’s it! Utica 21.’ ”

To impress, Samara liked to point out how much cream they kept in the refrigerator, to blanket such sleeping beauties as lump crabmeat riviera, chilled vichyssoise, and lobster newburg en casserole. When cream was a sign of the times, before leaner ones set in, and descriptors like “superb,” “delicate,” and “au jus” were in vogue. But it’s his other club, the Celebrity, whose timeline brings to mind the legendary “21”—a former speakeasy turned legit, catering to a stronghold of devotees with a menu of classics that barely ever changes.

In its current incarnation, the Celebrity bar is something of a keyhole itself, the Acheron you must pass on your way to the dining room.

A recent review of “21” in the New York Times pays gentle homage to a room that’s seen better days. “This is going to be a kind of love letter to a restaurant where the food is largely forgettable and the prices are almost always unwarranted,” the critic, Pete Wells, wrote in the opening paragraph. The burger and fries are still apparently tasty—the same fries Robby Benson ate with extra ketchup before jerking everybody’s tears in Death Be Not Proud—as one might hope at a healthy $35.

By the time Michael Douglas ordered Charlie Sheen a plate of steak tartare in Wall Street—way before he bloodied his nose in Central Park, in the rain, no less—the wolf was at the door. In 1985, the heirs of Jack and Charlie sold their interest in “21.” The restaurant is owned, for the time, by the Orient-Express Hotels group.

***

The Celebrity offers two signature salads, which sounds a little like forgery, but they get away with it. The vinaigrette that dresses the Syrian salad is set off by flecks of mint, the ingredient that makes it Syrian, I guess.

Samara’s ancestors come from a remote village in southern Lebanon called Jdeidet Marjeyoun, sandwiched between Israel and Syria. Joe Adwon’s family is too, same as the Bayouths of Skiatook. New York Times reporter Anthony Shadid, whose mother was a Samara, was building a house there when he died in Syria of an asthma attack.

The Columbia Gazetteer maps it out: “Marj ’Uyun (MAHRZH ei-YOON), town, S Lebanon, on a well-irrigated plain… Elevation 2,500 ft. Tobacco, cereals, oranges, olives. Former tourist center. Located 5 mi N of the Israeli border, it is the main urban and administrative center of the Israeli-controlled area (‘security zone’) of S Lebanon. Also spelled Merj ’Uyun and Marjioun.”

The second salad is the Caesar. The Celebrity did not invent the Caesar, but respects its origins. The key to a Caesar is emulsion, of lemon, oil, and egg yolk, which forces them to add that asterisked raw-egg disclaimer to the menu.

“I usually have—if I’m not having lobster—New Zealand whitefish,” said longtime customer Sharon King Davis. “And always a Caesar salad. It’s not your standard Caesar. Th at’s now a creamy white, packaged dressing, I guess from a bottle. This is the real Caesar.”

The real Caesar is the invention, the story goes, of Caesar Cardini, an Italian-American restaurateur who jumped back and forth over the border between San Diego and Tijuana, swatting at the gnats of Prohibition. In time, Cardini bottled his dressing, which is now the property of T. Marzetti Company, which also bottles such brands as Mamma Bella and Amish Kitchens. T. Marzetti is owned by a subsidiary called the Lancaster Colony Corporation, a Columbus, Ohio, company whose website homepage includes its daily trading price on the NASDAQ exchange.

The earliest Oklahomans farmed corn, beans, and squash. Our traditional restaurant triad, though, is steaks, chicken, and seafood, and in that order. “Enjoy the Original Freddie’s Bar-B-Que and Steak House,” says the type over the Sapulpa restaurant’s logo—a camel silhouetted in a desert oasis. Lobster and shrimp still survive on a few menus, lobster being the favored celebrant of the land-locked.

I met Joe Adwon for dinner at the Celebrity on a Monday, because that’s fried chicken night. “Fried chicken, fried shrimp, or fried catfish,” said the waitress, with mashed potatoes, green beans, a salad, and peach cobbler for $16.95. Joe gave me his cobbler because, at the Celebrity, he always drinks a Brandy Alexander for dessert. “A lot of people make them with ice,” Joe said. “No thank you.”

Lou Abraham, Samara’s liquor-distributor friend, called Mike one day to tell him about the cutest little nightclub for sale out east of town. Samara can’t remember who owned the building at the time. “One of the Sanditens,” he said. So, Samara called Joe Adwon’s father, Mitch. Mitchell V. Adwon had The Phoenicia, before he sold it to Don Abraham, and set up Ed Beshara at Beshara’s. “He backed Lebanese guys,” said Joe. It wasn’t until somebody burned the Celebrity down, two years into the reign of Samara, that they added a dining room.

Adwon Adwon, Joe’s grandfather, was a peddler. Tulsa bookstore legend Lewis Meyer wrote a chapter about this Adwon in his book Mostly Mama. In it, Mr. Meyer feasts upstairs on lamb chops, black-eyed peas, and mashed potatoes while, in the basement, Adwon goes through a bottle of Mama’s homemade wine—“the bouquet, the quality, the clearness, the lightness, the buoyancy, the delicious tastiness, and the wallop,” wrote Lewis Meyer, author also of Preposterous Papa and O the Sauce. Adwon Adwon sells Mama a trinket, then takes a shower with his clothes on.

Something keeps Samara coming in that front door, and it isn’t the ribeye.

Mike Samara takes no wine, and hardly any steak for a guy defined by it. “Me? I don’t eat steak three times a year. No, wait… we have a luncheon steak sandwich that I’ll eat maybe once a month.”

Suell Turner, on the other hand, can’t count how many steaks he’s eaten at the Celebrity. Only those he hasn’t. “What I like about this place, the food was always consistent. You couldn’t get a bad meal. I think, in 50 years, I’ve turned two steaks back.”

“It’s been there for 50 years for its sense of value and sense of nostalgia,” said Juniper’s Justin Thompson about the Celebrity. “When you last 20 years, you start dipping into that realm.”

***

Ameen Samara, Mike’s dad, would wait outside the train depot in Oklahoma City with his truck and haul people’s belongings for them to whatever claim they’d staked. Mike serves steaks. Service, in fact, begins with a smile. Then a handshake and a greeting, which was easier when he had eyes but doable by ear.

“Dad’s recall is amazing,” Nick said. “I’m not that way. I’m more of a backend operational person.”

“I worked at it,” Mike said. “It’s nothing special.”

“Tagging off ” is a game Mike and Nick play when one of them doesn’t recognize a particular patron. It might go something like this:

“Hey, Mike…”

“Good evening, how you doing!”

“Great. Good to see you. Hey ya, Nick …”

“Hey, Jerry, where you been?”

“Nick, get Jerry a drink.”

“Tagging off ” is a name game the Samaras play like a well-rosined bow. “Nobody likes to hear their name more than themselves,” Samara said, fiddling with the sunflowers on his van Gogh tie that, yes, he tied himself.

On the front lines, with every Christian crusade still bearing swords and banners and charlatans, Mike Samara, with the back slaps of several sturdy politicos, took up the cross of liquor by the drink.

“I was active in the Restaurant Association,” said Samara, who was a board member for decades. “We’d been here awhile, operating as a private club. They came to me.”

“Private” is the kicker. A “member” might pay a token fee once in a blue moon to have a bottle of spirits that you brought with you tucked somewhere in the vicinity of the bar with, theoretically, a sticker with your name stenciled on it. You’d then pay for a “set-up,” meaning ice and water or soda. “It gave the police and the officials something to go by,” Samara said, but a lot of liquor fell through the cracks. “You could come in to the club and say, ‘I’m John Williams and there’s a bottle of whiskey here with my name on it.’ But he wasn’t John Williams.” For a guy who doesn’t drink, Samara sure found himself in a pickle.

“Oklahoma has become the last state in the nation to legalize liquor by the drink as wet forces in the cities finally overcame the vote-getting power of the drys in the rural areas,” wrote somebody in the Associated Press Oklahoma City bureau on September 17, 1984. “Voters in this Bible Belt state, which did not repeal Prohibition until 1959, turned out in record numbers Tuesday and passed a constitutional amendment to allow liquor by the drink on a county-option basis.”

Liquor by the drink is one of those catchphrases that sounds clever but comes up two fingers short of a highball. We are living in Liquor-by-the-Drink A.D., which means you and I and your uncle can walk into an establishment that is legally authorized to serve alcohol and, provided we are of age, buy an adult beverage or three. In Liquor-by-the-Drink B.C., you could walk into a bar and pretend you were in Oz, and that there was a short, avuncular fella behind an imaginary curtain who would give you a drink, provided you had traveled the length of that yellow brick road with a girl in gingham, a passel of heart-sunk, brainless, scaredy-cat hangers-on, and a monkey on your back. If you got through that and got a drink, YOU were the wizard, and it was wonderful.

Next time you order an India pale ale or a pinot gris or a Jack & Coke, thank Democratic legislators Robert Cullison of Skiatook and E.C. Sanders of Oklahoma City. Th en thank George Josef Miskovsky Sr., a onetime welterweight boxing champ at the University of Oklahoma who traded blows in the Oklahoma legislature from 1939 to 1960. “In ’59,” said Joe Adwon, “he ran for right-to-work, reapportionment [an attempt to give population centers more political clout], repeal the liquor laws. He died in ’95.”

Joe’s grandmother was midwife during the birth of Mike Samara and George Miskovsky. Drink to that.

***

Liquor by the drink is one of those catchphrases that sounds clever but comes up two fingers short of a highball.

Way past his salad days, Samara was diagnosed with colon cancer. On the 1-to-4 scale set by the Classification of Malignant Tumors, he was beyond a 3.

“Seventy-eight was when I became ill. I said, ‘What’s the prognosis?’ They told me, ‘You’ve got to divest yourself of all your interests.’ So I did that. Most everything.”

Two years before, he’d opened up Utica 21. By 1983—when my parents took me to the 21 for my 20th and I found myself pissing in a stall in the shadow of Yankee slugger Dave Winfield—Samara was out. But not down.

“I had a pretty positive attitude and I just didn’t think I was gonna die. I was taking pretty good care of myself, physically, and I knew I had the best care possible.” He still rides a treadmill every day, paying it back.

Samara’s 89 now. Blind and hard of hearing. But he still ties his neckties one day at a time, and, with the help of a driver, seldom takes a rain check from the Celebrity. Maybe it’s easier, after all those years, not seeing. The wine-red walls can’t close in any tighter. The Sinatra songs remain the same. Something keeps Samara coming in that front door, and it isn’t the ribeye.

“I was telling my daughter that one of the things that I think is necessary is for the operator to have an insatiable desire for satisfying people.”

***

A few years ago, into the black and out of the blue, Samara renamed his Celebrity Club the Celebrity Restaurant, holding out hope. A new couple or two will come in every week and say, “We always thought you were a private club.” This ate at Samara for years, and it didn’t eat good. So he put up some new neon, changed the website, called the local press. Still, when Sharon King Davis not long ago suggested the Celebrity to her monthly meeting of friends, one of them said, “Isn’t that a strip club?”

“I know he wants to change it to the Celebrity Restaurant— he has—but it’s just the Celebrity Club to me.”

The truth is, it doesn’t need a name. Those who know go, and those who don’t won’t.

Originally published in This Land, Vol. 4 Issue 20. Oct. 15, 2013.