He stood naked by the roadside with a blanket draped around his hips, feebly reaching out for the glimmering cars as they passed in the morning light. He was almost too hideous to look at: Purple and black tracks streaked across his frail limbs, and his hollow eyes peered out from a pale, gray head shaved bald, eyebrows and all. Brandon Andres Green was not from hell, not exactly. He was from Broken Arrow, Oklahoma.

Over the course of the past six days, Green had been tied up in a Tulsa hotel room, where his mind was loaded with powerful psychoactives and his body ravaged. He was then driven 500 miles south and abandoned in a Texas field at night. Green had crawled through the darkness, the occasional moan of a distant car his only guide. Every few feet, he collapsed from exhaustion. By morning, he reached the road. He grasped at fistfuls of air, hoping that someone might notice him.

It was 8:11 a.m. when Patrolman Neal Mora of the Texas City Police Department passed. He wasn’t quite sure what he saw. He turned around, pulled over to the shoulder, then stepped out of his patrol car and approached the man cautiously.

“Help me, please,” Green gasped.

The emergency techs showed up and loaded Green gingerly into the ambulance. They ran a few tests on his vitals. He had about 45 minutes left to live.

Green was no innocent, not back then. He was making a few hundred dollars a week selling weed and Ecstasy in Tulsa when he met the wrong girl, who introduced him to the wrong guy. He couldn’t have known that he opened the gate to an underworld populated with federal agents, clandestine chemistry, and mystical orders. A world in which one man, Gordon Todd Skinner, felt at home.

It was April of 2003 when Green—18 at the time, still grinding out his final semester of high school—first laid eyes on Krystle Cole. She was the cute blonde in pigtails at a South Tulsa rave offering Ecstasy to Green’s friends. Green eyed her baggy pants, her form under a fitted t-shirt. He asked her to meet him in the hall, to see if he could buy 50 pills. He was a dealer too, he explained. She patted Green down, probing him with questions. He thought her paranoia was cute. Cole said she’d call him soon to negotiate a deal, and she did, around noon the next day.

They met at a Burger King near the University of Tulsa. Cole handed Green an envelope, then asked him for his car keys. Green waited inside while Cole searched his car. Wait 30 minutes before opening the envelope, Cole said. Inside were directions to a nearby Taco Bell, where Green found a note addressed to him hidden in the ladies’ room. Green saw a tall, bearded man in the parking lot, a guy he noticed at the rave the night before. The notes led Green to a pay phone in a sandwich shop, then a call led to the nearby Peace of Mind bookstore, where he found a final message hidden in a specific book that instructed him to meet Cole in the parking lot of a health food store.

The game took hours, ending with Cole inviting Green into her car. It was time to meet her chemist friend. Green saw the balding, bearded man—the same from the rave and from the Taco Bell parking lot—parked nearby. The man said he knew how to cook all sorts of drugs, and that he’d been involved in serious deals since he was a teenager; that he’d been all over the world, met with insiders, and even served a little time. And now he was looking for some help. Would Green be interested in some real work, a gig that involved a kilo of LSD in Amsterdam? Cole made the introduction: Brandon, meet Gordon Todd Skinner.

Around Skinner, Green felt intoxicated. At the time, Green was a senior at Victory Christian School—a pretty boy, slight of build with long, golden hair and blue eyes. He was naïve and easily entertained, the kind of guy who would get fruited to the gills at raves. Skinner was everything Green was not: big, strong, hyper-intelligent, worldly, and otherworldly.

Green needed to get a legitimate job to distract the authorities, they told him. He would need to abandon the party scene for a discrete, seemingly ordinary life. If everything went well, and Green proved himself to be a talented understudy, then they could talk about the transaction in Amsterdam. It could bring in millions. Green was excited, and terrified. Skinner and Cole were grooming Green to be a better drug dealer. Just the week before he bought a fake Mazzio’s Pizza uniform to fool his parents into thinking he had an after-school job. Now two accomplished drug traffickers clamored to mentor him. He never heard of Gordon Todd Skinner or Krystle Cole before.

“You realize you’re in too deep to back out now,” Skinner told Green.

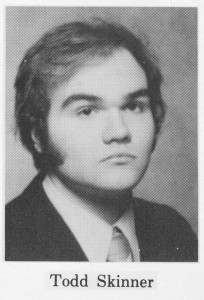

During his high school years in the early 1980s, Gordon Todd Skinner often showed up to Cascia Hall Preparatory School in his blue blazer, with the school crest proudly emblazoned on his chest. On free dress days, he wore a karate gi, or sometimes a tux, to school. A classmate of Skinner’s recalls seeing him arrive in a 1957 Bentley S1. He wore a full-length camel-hair coat.

A tall, fleshy math geek, Skinner didn’t play sports like football or basketball. Instead, he dominated at chess.

“I played him one afternoon and beat him,” the classmate remembered. “But as the game drew closer to a conclusion, and Skinner realized he would certainly lose, he began taunting me for not finishing him off quickly enough. He said my finishing game was weak. That’s just the type of guy Gordon Todd Skinner was. He always had to be in control of the situation. Even when he really wasn’t.”

Chemistry was a breeze. He tinkered with molecular structures. Chess was a longstanding passion, but by the age of 15, Skinner discovered another obsession: drugs, and everything related. At 16, he could extract psychedelic tryptamines from plant life. He offered them to friends.

“All of my high school friends just lined up to take anything that I had, and it was—they were volunteering, so it wasn’t a problem,” Skinner says, fanning his fingers over the cafeteria table in Joseph Harp Correctional Center in Lexington, Oklahoma, a world and a life away from his Tulsa prep school. His hair is mostly gray now, the crown of his head smooth as a cremini’s cap.

Skinner’s mother, a Tulsa business woman named Katherine Magrini, married Gary Lee Magrini. Skinner’s stepfather was a special criminal agent with the U.S. Treasury Department, which, at the time, handled scores of drug investigations. Federal agents visited the Magrini home regularly. From an early age, Skinner learned that he could dabble in the world of drugs right under the government’s nose. Either nobody cared, or nobody noticed.

Skinner tried stronger drugs on his friends, studying them like insects. He was known to bring a tank of nitrous oxide to school so he and his pals could inhale in the bathroom between classes. One weekend, according to a classmate, Skinner experimented on another student, dosing him heavily with something he’d conjured. The teen was later found in front of a full-length mirror, naked and talking to his reflection. He tried to negotiate a cocaine deal with an oak tree.

“I was just a scientist saying, ‘Try this out.’ And unfortunately, they were all just guinea pigs in line,” Skinner recalls. “Some of them thought it was great, and some of them don’t talk to me to this day over it.”

Religion and psychedelics enjoy a marriage over millennia. One of the most evocative myths pertains to Soma, or Chandra, the havoc-creating moon lord of plants in Vedic Brahmanism. “Let Indra drink, O Soma, of thy juice for wisdom,” the Rig Veda proclaims. The ethnomycologist R. Gordon Wasson equated Soma with the psychedelic mushroom amanita muscaria, the same mushroom that appears in Siberian folklore and ancient Central American pottery. The use of mushrooms, fungi, and other plant-related hallucinogens permeate indigenous spiritual traditions, but it wasn’t until 1938 that a Swiss scientist, Albert Hofmann, tried synthesizing ergotamine (an extract of ergot fungi) and wound up with lysergic acid diethylamide, or LSD. Reports quickly spread about its mind-altering effects. Even the U.S. government was curious.

Dr. Frank Olson, a biological warfare specialist, stayed at the Hotel Statler in New York City. Unbeknownst to him, the Central Intelligence Agency dosed him with enough LSD to seriously impair his mental state. On Saturday, November 28, 1953, Olson’s trip ended when he was pushed from, thrown out, or jumped out of the glass window of his room and plummeted 10 floors down. The Frederick News-Post said Olson was depressed and complained of ulcers. Today, we know his death was the result of a covert CIA project known as MK-Ultra, which dosed unwitting men, women, and children with LSD for scientific research. The program was declassified in 2001, but nobody knows how many died as a result of the experimentation. Olson’s family settled with the U.S. government for $750,000.

The CIA’s drug experimentation projects took root post-WWII. Initially they focused on discovering new techniques for mind control, torture, and brainwashing. Similar CIA projects grew in scope and ambition during the 1950s, and included subjects like future counterculture figures such as Ken Kesey, Robert Hunter, and Ted Kaczynski. In his book The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, Tom Wolfe documented the transition of LSD into American mainstream culture. By the late 1960s, LSD was on the tips of myriad tongues, with about 20,000 being introduced to the drug annually.

In 1966, a gang of sophisticated, elusive peacenik drug smugglers called “The Brotherhood of Eternal Love” became a prolific supplier of LSD stateside and to soldiers fighting the Vietnam War. Using a retail front called Mystic Arts World in Laguna Beach, California, the Brotherhood began its crusade to deliver LSD to the masses, for the purpose of spiritual enlightenment. Under their auspices, the ingenious chemist Nick Sand produced 3.6 million hits of acid in 1969. His product “Orange Sunshine” was the most popular form of LSD of all time.

When core members of The Brotherhood of Eternal Love were busted in August of 1972, Nick Sand was among those whose futures were blotted. Rumor had it that a bright, young trust-fund kid named Leonard Pickard, also an aspiring chemist, donated to Sand’s legal battle[1]. In 1976, Sand was convicted and sentenced to 15 years. He appealed his case on the technicality that he actually produced a close variant of LSD called ALD-52, which was legal at the time. Sand was released on a $50,000 bail and disappeared into the ether. Two years later, Pickard, then a student at Stanford, was charged with attempting to manufacture a controlled substance[2].

In the mid-to-late ‘70s, LSD production was interrupted by law enforcement. Availability remained comparably low for the next 30 years. The controlled substance was, it seemed, under control. Cocaine-fueled hustlers discoed across illuminated dance floors, Elvis left the building with 14 different compounds in his body, and Nancy Reagan coached children to “Just Say No.” Meanwhile, across the desert, in the middle of the country, a new maestro of the underground drug industry was loosed upon the land.

While Skinner lab-ratted his pals at Cascia Hall, at home he was submerged in a federal alphabet soup. Skinner’s stepfather, Magrini, earned an appointment as criminal enforcement agent for the Internal Revenue Service[3], and the front door of the Magrini house, according to Skinner, revolved with the constant stream of G-men from the FBI, DEA, IRS, and CBP[4]. Many of them were soldiers in the War on Drugs, a governmental prohibition campaign that was coined by President Richard Nixon and escalated by President Ronald Reagan. In 1986, Congress passed the Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which poured an additional $1.7 billion into funding the War on Drugs.

“They all came to our house and ate at our parties—I grew up with these guys. They talked shop non-stop,” says Skinner, calling from prison now. “The FBI guys would ask me to look into stuff for them, and I did this on a regular basis.”

Skinner is serving life plus 90 years for kidnapping-related charges. His cellmates refer to him as Dr. Lecter. He distrusts the FBI more than any other agency, and warns that the line is being monitored and that it might be blocked, because “that’s how they do me here.”

Skinner’s ties to a number of other government agencies deepened in step with his drug experimentation repertoire. He didn’t really enjoy marijuana or other common drugs, but gravitated toward entheogens, the sorts of drugs that shamans and other spiritualists use. He read most every book he could find on the matter. One of his favorite libraries was Peace of Mind bookstore in Tulsa. Barry Bilder, the owner, became a longtime friend to Skinner.

“When I met him, Todd was still in high school,” Bilder said. “He would come in and buy all these drug books, and he had a tremendous collection that he bought over a period of years.”

During his early years of studying, Skinner didn’t involve himself in his experiments with psychedelics, preferring to observe their effects on his classmates and friends. Later, he started the journey within.

“I was a little nervous messing with the neurocomplex of the mind,” Skinner once explained to a courtroom.

At around 19, Skinner was ready to step into the fairy ring. He had acquired 10,000 peyote buttons on behalf of a Native American church and extracted a variety of alkaloids from the supply. He decided he would take the synthesized mescaline.

“It was profound,” Skinner says. “That’s all I can tell you… I saw colors, and I was in a room that was small and all of a sudden it was like a set on the Ponderosa.”

Skinner then decided to push the experience further. He fasted for two weeks, then consumed 52 peyote buttons.

“I rolled over and I could just see all the stars and it was amazing,” Skinner says, smiling up at the fluorescent lights. “I had what I’d call a peak experience—and I’d call it religious because you become instantly connected with everything in the universe. That was a turning point for me. I was a scientist prior to that.”

In the natural camp of entheogens, you’ve got peyote, psilocybin mushrooms, salvia, and ayahuasca, to name a few; LSD, MDMA[5], and 2C-B are synthetic. Then there’s Todd Skinner’s catalog, a menagerie of exotic entheogens that requires the help of a chemist to decipher. When Skinner took the stand in January 2003, the judge asked him what drugs he had used. Skinner replied:

I would like to start with the ones I don’t use. I never used, to the best of my knowledge, any form of tobacco plant. I never used methamphetamine. Never used cocaine… I have not used street drugs in general. I have avoided most street drugs. I’ve not used PCP. The reason I’m doing the ‘nots’ is because I’ve done so many unusual analogues that the list gets to be long.

According to a list he provided to the courts, the number of all the drugs he ingested, inhaled, injected, inserted, snorted, or otherwise introduced into his body comes to 163, and is much higher when counting the derivatives of certain substances. When Skinner elaborated on a particular drug, he conveyed the sort of obsession you’d expect from a vintner.

I went through an elaborate process and consumed ibotenic acid, which would have been the active constituent. I rarely did this. I was nervous about the research, because of the decarboxylation of ibotenic acid that converts to muscimol, which is an active constituent of fly agaric or Amanita muscaria.

Skinner can wax poetic on PCP-A receptors and the differences between pharmahuascas and 5-fluoro-alpha-methyltryptamine, but when the judge finally asked Skinner why he wanted to use entheogens, Skinner went flush.

I seem to have an idiosyncratic response to entheogens, that they are—have—maybe that’s arrogant, so I’ve got to be careful. They are very spiritual and sacramental things. I do not use these—I think you put it ‘recreationally,’ and I take offense to that, unfortunately, because I do not take these things recreationally. These are sacraments to me.

To achieve such a communion, Skinner employed a concoction of pyschoactives he called “The Eucharist”: a communion wafer laced with a panoply of lysergamides ranging from ALD-52 to extract of morning glory seeds, with a sip of ergot wine. Skinner conducted the ceremonies with “the sacrament,” and regularly administered the rite before large congregations of friends.

Numerous accounts from Skinner’s associates describe seeing Skinner act in a priestly manner, conferring the hallucinogenic host upon eager tongues and offering a chalice to waiting lips. Within half an hour, his sheep met god. Or the devil.

“A lot of people, when they met Todd at his highest, they would say something to me like, ‘Barry, that guy is the Buddha,’ ” Bilder said. “But what I’m suggesting is that Todd had something in his being, this thing that wasn’t right. He had made a pact early on in his life, maybe it was even in previous existences, where he said, ‘This is what I’m gonna do: I’m going to be here to create havoc.’ ”

On the witness stand in 2003, Gordon Todd Skinner was 39 years old and speaking like a priest of Soma[6]. But earlier in his spiritual journey, Skinner was seduced into another underworld, one of unholy adventures, a world where drugs were both faith and works. As a young man, Skinner partook in the most secretive of all arts. He became a government informant.

Skinner’s first notable case came in 1983 by way of a money-laundering scheme; he initiated the case by calling Agent McLean with the FBI. In a later and more significant operation, Skinner helped HIDTA, High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, Group #2 out of Florida (primarily managed by CBP), set up a complex sting operation with a man named Boris Olarte who was in the federal witness protection program[7]. In 1989, Olarte was then used to extradite and arrest José Rafael Abello Silva, a Columbian cocaine smuggler. His arrest contributed to the downfall of the Medellín drug cartel. As he informed, Skinner gathered intelligence on how government agencies dealt with drugs. Work as an informant turned out to be great training for a person interested in the trade, but it wasn’t enough to help Skinner avoid prosecution.

Earlier that year, Skinner was arrested and jailed in New Jersey for distribution of marijuana. Skinner’s bail was set at one million dollars. While serving time, he met fellow inmate William Hauck, who was incarcerated for a sex offense[8]. Through the ‘90s, Hauck surfaced intermittently in Skinner’s life, usually as a truck driver for Katherine Magrini’s company, but sometimes as an accessory to Skinner’s drug-related transactions. Skinner and Hauck were never really friends, perhaps because Skinner suspected Hauck of having longstanding ties to government agencies. Skinner’s suspicions remained benign, until Hauck figured much larger in Skinner’s life.

The Silo Testimonies

Todd Skinner wasn’t just a psychedelic spiritualist, nor was he merely a government informant. He was business-minded, and he understood the high demand for entheogens. If he could just find the right chemist—someone who knew how to set up a sophisticated lab where LSD could be produced—the possibilities and the profits were boundless. Alfred Savinelli, a friend of Skinner’s and part of the entheogen community, recalls when Skinner asked him if he knew where he could meet an elusive, gifted chemist named Leonard Pickard. Rumor had it Pickard was advancing the field of LSD chemistry. Savinelli knew Pickard. He felt Skinner’s ambition and Pickard’s naïveté would make a disastrous combination. Salvinelli shrugged Skinner off.

Pickard was still around, just not very visible. After serving time in the ‘70s for possession and manufacturing, Pickard seemingly vanished from the scene, until he was jailed in the late ‘80s. He did five years for manufacturing. Later, word got around that Pickard was in the DEA’s pocket.

Throughout the 1990s, Pickard continued moving in hallucinogenic circles. While taking classes at UC Berkeley, Pickard attended a series of potlucks—dinner conversations that centered on consciousness studies. He lived in a Zen center, earned a master’s degree from Harvard, and studied the migration of LSD use. Late in the decade, his associates claimed to see the professorial Pickard dealing with large amounts of loot. Pickard explained away any secretive behavior as related to his work for the FBI, DEA, and other agencies.

The similarities between Pickard and Skinner were extensive: both were entheogen enthusiasts, capable clandestine chemists, lawbreakers, and informants for the government. When they met each other at the 1997 Entheobotany Shamanic Plant Science Conference[9] in San Francisco, it was as though their convergence were ordained by a fungal power.

“When I met him, [Skinner] was using exotic structures every week or every few days,” Pickard told Rolling Stone. “He loved to eat ayahuasca and its various analogues.”

Pickard says that Skinner was offering research grants at the conference, which piqued his pockets.

“Basically I just made up quite a story to [Pickard] and told him that we could possibly get some money from [billionaire Warren] Buffett,” Skinner later revealed on the witness stand. “And I had quite a bit of fun with that one, but it really, in the end, upset him quite a bit.”

Pickard and Skinner met several times at Skinner’s house in Stinson Beach, California (its former occupant was Jerry Garcia). It was a party pad frequented by insiders of the entheogen world and the perfect place for Pickard and Skinner to talk business.

Just a year earlier, Skinner had acquired an Atlas-E missile silo at 16795 Say Road in Wamego, Kansas. He lived there and planned to use it as a facility for his mother’s industrial manufacturing company, Gardner Spring Incorporated. As a home, it provided Skinner two of the things he valued immensely: seclusion and privacy.

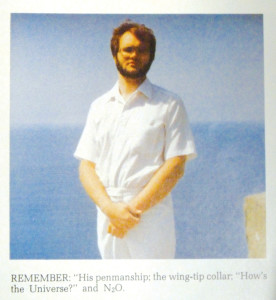

The missile silo was the ultimate Skinner Box. He renovated the military complex, adding a luxury sound system and a group-sized hot tub. Llamas and Clydesdale horses roamed above ground while pretty girls and hardcore partiers voyaged to chemical wonderlands below[10]. Skinner’s silo became a vortex of local gossip, with stories and rumors that continue to percolate about Wamego to this day.

Legends of Pickard and Skinner’s partnership circulated the globe and remain debated in countless online forums. Rolling Stone magazine presented Pickard’s account of the silo years in their 2001 article “The Acid King,” which portrayed Skinner as a Kurtz-like con man whose ghoulish escapades into experimentation culminate with the fatal overdose of a friend in April of 1999. Skinner’s version of events, however, differs from Pickard’s.

Skinner’s Recollection

Skinner testified that he and Pickard mapped out a working business and started a clandestine lab at a house in Aspen, Colorado. That location wasn’t an ideal chemical processing facility, though. The house was in bad condition, which meant a continual parade of plumbers and carpenters. That, plus high rent and chemical spills sent Pickard and Skinner packing to Santa Fe, likely in late ’98 or early ‘99. Turned out the move was smart financially.

When Judge Richard Roberts of Topeka, Kansas, asked Skinner how much LSD was being made and how often during the Santa Fe LSD operation, Skinner couldn’t answer him exactly. He wasn’t there often enough during the manufacturing process to know volume, he said. Skinner says he did manage cash flow from a West Coast figure named “Petaluma Al,” and estimated that within one year’s time the Santa Fe operation generated about $30 million dollars in revenue—roughly enough acid to send all of Spain and France tripping.

The problem with a successful LSD lab is that it can attract attention, and then all those boxes of tax-free, dirty money create paranoia[11]. It’s unwise to operate out of the same place for more than two years, which is why Pickard, Clyde Apperson (their set-up and takedown guy), and Skinner went prospecting in Kansas. They looked at an Atlas-F missile silo near Salina, Kansas—a short drive from Skinner’s own Atlas-E silo (the main difference between the two types of silos is that Atlas-F missiles were stored vertically, while Atlas-E were horizontal). They couldn’t use Skinner’s silo because the property’s paperwork had Skinner’s name all over it, making it susceptible to close investigation. By this point, the government was keeping tabs on Skinner at the Wamego base, but the Atlas-F silo had certain features that made government intrusion nearly impossible.

“[There were] Very little above-ground ways of doing observation—a heavy-duty structure to where it would be harder to break into and with lots of space being around it and a military fence…” Skinner recalled from the stand during Pickard’s trial. “You would be able to tell if you were under surveillance.”

Tim Schwartz owned the Atlas-F silo. Schwartz was the property dealer who sold Skinner the silo in Wamego. Skinner told Schwartz he was interested in using the Atlas-F, so Schwartz struck an informal agreement with Skinner that allowed him to use the Atlas-F base while Schwartz was traveling the country. Skinner claimed that not long after, around December of 1999, he, Pickard, and Apperson began using the Atlas-F missile base for their LSD operation. It was the Wamego missile base, however, that began to wave a red flag.

With the successful setup at the Atlas-F base, the first months of the new millennium held a promise of unprecedented profits from drug trafficking. That’s when a balding and bearded Gordon Todd Skinner first met Krystle Cole at a Topeka gentlemen’s club, where she was an 18-year-old pigtailed stripper who performed a country-girl-gone-bad routine. When she saw Skinner enter the club, Cole remembers thinking to herself, “What a sick-o! Did Amish men really go into strip clubs? Weird!” But then they fell into a deep conversation. Soon, Skinner convinced Cole to join him at his missile base.

Cole and Skinner were the sort of soul mates who shared the same order of the same genus of the same species. In the dank innards of Skinner’s silo, their viscid bodies fused over LSD and Ecstasy trips. They experimented with hallucinogenic suppositories.

“We knew how deeply we loved each other,” Cole recalls in her exclamation-heavy 2007 book Lysergic, which she claims has been optioned for film production. “No questions. The deepest love ever, a sacred love. We worshipped each other as divine interlocking pieces of god.”

In one cinematic chapter, Cole and Skinner meet up with a suave Pickard and his Russian fiancée, Natasha. The four enjoyed a high-rolling, free-loving weekend in Las Vegas.

Within three years of starting their romance, Skinner and Cole will participate in a blood-dripping, vomit-spewing incident that will end with kidnapping charges for both of them.

VICE magazine’s short documentary, “High on Krystle,” offers a peek into the life of Skinner’s comrade in expanded consciousness. During the video, the cosmic Cole takes the host, Hamilton Morris, on a giggly tour of the Wamego missile base. She explains how the corrugated, cylindrical corridors “are really fun when you’re tripping, because they’ll start swirling on you.”

Cole left a detail out of Lysergic’s love story: Skinner’s other love. Around 1997, he started dating a woman named Emily Ragan. When Skinner met Cole at the strip club, it wasn’t a random encounter—he was interviewing her for a job as his personal assistant.

“Krystle was a great valet,” he remembers, adding, “She was very well organized.”

At the same time Cole was finding herself enmeshed with Skinner’s soul, Skinner was growing closer to Ragan as well. In September of 2000, Skinner married Ragan. They had a daughter together, and divorced the following year. Ragan taught chemistry at the University of Tulsa. Through her current husband, she declined to comment for this story. Skinner says he eventually fell in love with Cole.

While Skinner’s testimony during the Pickard trial depicted an industrious atmosphere at the silo, Cole had a different take, likening the milieu to that of an entheogenic monastery. Cole recalls lots of nudity and wild parties where people used IVs to blast themselves into deliria. Somewhere in the subterranean haze, Krystle recalled a ritual in which Skinner initiated her into an order using a golden chalice, ergot wine, and ancient Chaldean prayers.

In Lysergic, she theorizes that the Last Supper might have been similarly infested.

“Doesn’t this seem a little like the communion of Christianity?” Cole asks.

Depressed and recently divorced, Tim Schwartz, the Atlas-F’s property owner, committed suicide in March of 2000. Someone was bound to reclaim the silo soon. Schwartz’s father finally contacted Skinner in July and asked him to immediately move out any belongings and to remove the locks. Both Apperson and Pickard were away at the time, so Skinner made the only choice he could: He gathered a few trusted friends and moved the entire lab, chemicals and all, out of the Atlas-F silo and into his Atlas-E residence in Wamego[12]. Fearing Pickard and Apperson’s fury, Skinner lied and told them that he had moved the lab to a facility near Topeka.

The LSD operation, in Skinner’s mind, was untenable. He questioned Pickard’s integrity, and felt as though the entire effort was polluted by corruption and greed. Worst of all, he suspected that Pickard may have been involved in the murder of an informant[13]. Around August of 2000, he expressed to Krystle Cole and others that he was going to inform on Pickard. In a later meeting with Pickard in California, Skinner explained that he was planning to marry Emily Ragan and would return the lab equipment soon thereafter.

The DEA’s silo investigation, “Operation White Rabbit,” began in October 2000, when Skinner decided to approach the government as an informant. In the weeks that followed, Skinner took DEA agents into the Wamego silo under the guise of giving a property tour, and he recorded calls he made to Pickard.

On November 6, 2000, Clyde Apperson pulled his Ryder truck out of the Wamego missile silo property. Inside was some of the LSD lab equipment they had reclaimed from the Atlas-E silo grounds, along with a small amount of precursor[14]. Pickard trailed Apperson in a Buick LeSabre. They hadn’t made it far before their caravan was pulled over by the Kansas Highway Patrol. Pickard, a marathon runner, took off running into the cold Kansas fields, only to be found by a farmer and arrested a day later.

During the ensuing trial, Pickard’s worst suspicions were confirmed. Skinner had signed the DEA’s Confidential Source Agreement form. It offered some level of immunity, but not enough to make him feel safe. On October 19, the Department of Justice struck a deal with Skinner, offering him an incredibly broad umbrella of protection in a letter that stated:

In exchange for your agreement to cooperate with the undersigned and/or other federal agents, the United States Department of Justice, Narcotic and Dangerous Drug Section agrees that no statement or other information (including documents) given by you during this and subsequent meetings will be used directly or indirectly against you in any criminal case…

Skinner was ready to spill, an act commemorated in a 706-page document called The Transcript of the Testimony of Gordon Todd Skinner Had Before Honorable Richard D. Rogers and a Jury of 12 on January 28, 2003.

“How is cooperation such as you’re doing viewed in that [drug] community?” the judge asked Skinner.

“In certain segments, this is the death penalty,” Skinner replied.

Skinner’s reasoning involved more than just saving himself legally, he claims; it was an indictment of his own character. He was a product of a Catholic private school, a man who was willing to testify against his own partners in an illegal-drug enterprise, and an ambitious businessman. He explained it this way:

I was a member of a system [the Brotherhood], the whole entire lineage of the sacraments were contaminated fundamentally,” he told the court. “This was an absolute violation at the highest level of an organization of a spiritual means, even though the deeper I looked into this organization, the more corrupt I found it to be. And even the corruption was on myself.

When Pickard had a chance to counter Skinner’s testimony, his story was a wholesale refutation of Skinner’s account. The Santa Fe operation never existed as such, Pickard claimed. Instead, it was a lab established by Skinner to manufacture ayahuasca. He claimed only incidental contact with Skinner until late 1999, and after that point, “perhaps a dinner each month” until Pickard’s arrest in Kansas. Skinner’s entire testimony was essentially another one of Skinner’s elaborate con games, Pickard thought, one in which Pickard was merely the patsy.

“Many other individuals have been the victims of [Skinner’s] grifting, unwitting of his actual background,” Pickard wrote in a recent email. “He has the capacity to weave convincing fictions about others, both real persons and imaginary ones, and extend these confabulations for days in the greatest detail.”

But a slew of witness testimonies also appeared inconsistent with Pickard’s defense. Alfred Savinelli, who provided some of the lab equipment, said that Pickard made him worry for his own safety and that of his family[15]. Another man, David Haley, claimed that Pickard had paid him $300,000 to lease a house in Santa Fe for a two-year period. DEA Agent Karl Nichols offered a number of phone records and financial transactions that provoked suspicion.

On November 25, 2003, Leonard Pickard and Clyde Apperson were found guilty of conspiring to manufacture, distribute, and dispense 10 grams or more of a “mixture” or a substance containing a detectable amount of LSD. But if not for his arrangement with the government, Gordon Todd Skinner might have stood with them. In a 2004 statement by DEA Administrator Karen P. Tandy:

DEA dismantled the world’s leading LSD manufacturing organization headed by William Leonard Pickard. This was the single largest seizure of an operable LSD lab in DEA’s history. On November 6, 2000, DEA agents seized from an abandoned missile silo located near Wamego, Kansas, approximately 91 pounds of LSD, 215 pounds of lysergic acid (an LSD precursor chemical), 52 pounds of iso-LSD (an LSD manufacturing by-product), and 42 pounds of ergocristine… Since that operation, reported LSD availability declined by 95 percent nationwide.

The press release was hyperbolic. The DEA reportedly captured 91 pounds of a substance that contained minute amounts of LSD. Testimony suggested the presence of only an estimated seven ounces of LSD. If Skinner or Pickard produced or stockpiled a larger amount of LSD, it had essentially vanished from the DEA’s grasp1[16].

Pickard is serving two life sentences. Apperson received 30 years. Skinner walked. The entheogen community, which was just gaining ground with legitimate research and studies, fell apart.

“It was torpedoed,” recalls Savinelli. “Everybody dug in deep and disappeared and sought protection. I’ve stayed away from most of my friends for a decade.”

Life Out of the Silo

In early 2003, a chapter of life closed on Gordon Todd Skinner. In the eyes of some, he was an enlightened spiritualist, a demonic criminal, a brilliant businessman, or a gifted liar. The spiritual community that he once prized was obliterated, he had turned on his business partners and ruined an empire, his health began to fail him, and the heat from government agencies surrounded him.

“I was in a really good mood,” Skinner says, “I know you’d have a hard time believing that, but I was under enormous stress prior to the trial… When I got off the stand and I was released by the judge, I was one happy dude—I was ready to leave the United States.”

Skinner’s high spirits would not last long. They flew out the door, along with Krystle Cole.

Cole first realized she loved Todd Skinner in Las Vegas, the same place she claimed to party with Pickard. But that was 2000, and now, in 2003, she had a supplemental love: the 18-year-old drug dealer Brandon Green. Cole, the older woman at 21, stood before a mirror in her hotel room. Green watched her practice an “I’m just a small-town girl” alibi, the same one she’d rehearsed every night of their romantic getaway. She had the alibi down solid.

Cole and Green had escaped from Skinner because they feared him. When they first met, Skinner and Green bonded over their love of drugs and travel. They told each other about their favorite trips (the literal ones, including destinations like the Netherlands and Germany). Initially, Green suspected that Cole’s relationship with Skinner wasn’t anything traditional, and in time, it became apparent to him that they weren’t exclusive to one another at all. Green cultivated a fondness for Cole, and she for him. At first, Skinner acted as if he wasn’t affected by the intimacy between the two. But then, by late spring of 2003, Green noticed that Skinner’s demeanor changed. He slept less and lost a significant amount of weight. He grew disheveled and unkempt. Skinner was under inevitable stress as the Pickard trial progressed in a Kansas courtroom, his enterprise with Pickard had ground to a halt, and he was more than just a bright dot on the law enforcement radar screen.

One night, Skinner showed up at Green’s apartment while he was away, took Cole from the living room by force, and then sped away with her. Cole claimed Skinner had threatened to drive off a bridge.

“Todd has an anger about him that is very scary,” recalls Green, who sounds a little nervous. “You know when his face turns red—and he is a big guy. He just seems crazy. You don’t want to piss him off.” It’s a quiet afternoon at a restaurant in Norman, Oklahoma, near Green’s home. It’s been 10 years since the kidnapping, and this is the first time he’s ever told his side in its entirety.

That incident shocked Green and Cole enough to seek a protective order against Skinner in early June of 2003. The order was never served; Cole and Green canceled it when Skinner promised to pay them off in MDMA pills. Hoping to distance themselves from Skinner, Cole and Green then turned to the DEA to inform them of Skinner’s drug-related activities. Cole claimed Skinner had an MDMA lab at his mother’s company in Tulsa. Green admitted to dealing for Skinner.

“I felt like Todd was going to kill her eventually,” Green says. “And whether I loved her or not, my sole responsibility was to keep Krystle safe.”

Green and Cole escaped to Las Vegas where they stayed in hotels and devised a plan to leave the country together. It was there, in the dry Nevada valley, that reality paid a rare visit.

“She [Krystle] realized that I’m a little boy of 18 and that I didn’t have any finances, especially when there were no drugs to sell,” Green recalls. “I wasn’t going to be able to take care of her.”

A few days into the Vegas trip, Cole asked Green to pick up some supplies from a health food store across town. When he returned, she was gone. She left a handwritten note for Green telling him that she had left for California to secure documents so the two of them could flee the country, and that he should return to Tulsa to await further contact1[17]. Cole then returned to Tulsa, where she resumed her relationship with Skinner, who had plenty of cash and drugs[18]. Cole requested a protective order against Skinner on June 9, 2003; two weeks later, she showed up for an intimate, private gathering at Skinner’s mother’s house. With a small group of friends present, she planted herself next to Skinner and married him.

Confused, full of fear, and loathing the prospect of love lost, Green drove out of the Nevada desert and back to Oklahoma. He returned to the apartment he shared with Cole in Tulsa. After a few nights there, he came home and found Gordon Todd Skinner on his couch, uninvited.

“I couldn’t believe it,” Green says, “This was the very man I was hiding from and he was asleep in my living room.”

What surprised Green even more, however, was that Skinner didn’t seem upset with him. Skinner thanked Green for taking care of Cole. Skinner said he planned to leave the country with both of them to avoid governmental prosecution and offered up an idea for the three of them to begin a business venture that involved dredging harbors in the Caribbean. Green, still in love with Cole, felt unsure about the situation but agreed to the plans. Perhaps, he thought, he and Cole could ditch Skinner upon their arrival there. When he tried contacting Cole to discuss it with her, she wouldn’t return his calls. Finally, Green met up with Skinner and Cole. Skinner handed him a document, a marriage certificate binding Cole and Skinner together. Skinner, Green claims, said that his marriage to Cole was just for legal reasons, and implied that it was fine with him if Green wanted to resume his relationship with Cole[19].

“I didn’t really know what to say and I just left,” says Green. “And I was just numb. I went back to my roach-infested ghetto apartment and just sat there next to concrete, just up on some bricks, and just sat there.”

For the next several days, Skinner, Cole, and Green did what drug users do. They continued to hang out and party[20]. Green remembers having sex with Cole while Skinner was showering. He didn’t think Skinner would mind if he slept with his new bride, and Cole certainly didn’t object.

Room 1411

From “Charges Allege Teen Kidnapped, Tortured,” in the Tulsa World, reported on September 12, 2003:

Three people were charged Thursday in a Tulsa County kidnapping in which the victim reportedly was held for six days and repeatedly tortured. Gordon Todd Skinner, Krystle Ann Cole Skinner and William Ernest Hauck were charged with kidnapping a Broken Arrow teenager during the Fourth of July weekend at the DoubleTree Hotel Downtown, 616 W. Seventh St. Police allege that the victim, 18, was held captive in the hotel, where he was tortured with beatings and chemical injections… The teen, broken, bloody and dehydrated, was found July 11 in a field in Texas City, Texas. Police picked him up and took him to a hospital.

From Skinner vs. State of Oklahoma, June 11, 2009:

Even a careful review of the record in this case leaves unanswered many questions about what exactly happened to 18-year-old Brandon Green, beginning over the Fourth of July weekend in 2003, at the hands of defendant Gordon Todd Skinner (“Skinner”), and with the assistance of his co-defendants Krystle Ann Cole Skinner (“Cole”) and William Earnest Hauck (“Hauck”). It is even more unclear why it happened.

Originally, three people were charged in Green’s kidnapping: Skinner, Cole, and Skinner’s associate William Hauck. A fourth person, Kristi Roberts, never charged criminally, appears intermittently. Initially, they had all come together to celebrate the Fourth of July at the DoubleTree, some of them hoping to continue on to the Caribbean. Then, Brandon Green partook in a psychedelic rite, and everything went wrong. Each person’s story is collected here, gathered from an assembly of interviews, public records, and private accounts. While no single story is endorsed, some light, however broken, reflects from their assembly.

View the medical diagram of Green’s injuries here (pdf 2Mb).

Kristi Roberts: “Everything Will Be All Right”

“It’s not as bad as it looks,” Krystle Cole says to Kristi Roberts.

It’s late at night on July 4 and Roberts pokes her head into Room 1411 of the DoubleTree Hotel in downtown Tulsa. Roberts had just met Cole and Skinner a few weeks ago, and they’d partied hard before, but not like this. Overturned food trays, fast-food containers, remnants of half-eaten meals, pillows, towels and linens are strewn across the room. There’s dried vomit caked on the carpet. As she tiptoes toward the bathroom, she’s bewildered by the site that unfolds.

Brandon Green, her “weed man,” lies on the tile, his pants below his knees. Duct tape is strapped around his head and mouth, and his hands are taped behind his back and to his ankles. A KFC drink cup covers his genitals. Green had introduced her to Cole and Skinner, and now this? From behind her, Cole and Skinner explain that Green dropped way too much acid last night, Skinner estimates 15 sacramental wafers, and was out of control. They had to tie him up.

Roberts rummages around the room, finds a steak knife, and cuts Green free. He’s not making much sense. Roberts has never seen anyone tripping as hard as he is. She draws a warm bath for him, and she sees Green’s scrotum is so swollen it looks as though he has only one testicle. Green’s not in the bath long before he defecates in the tub. Skinner steps forward and pulls Green out, and lifts him onto the bed. Skinner seems more agitated than usual. Roberts

strokes Green’s hair, telling him that everything will be all right.

With Skinner and Cole gone, Green calms down. He asks Roberts the same thing, a hundred times over: Does Krystle love me? Can you find out if she still loves me? Roberts promises to find out, but when Cole returns to the room she asks Roberts to go with her downstairs to ask the attendant something. When they get back up to the room, Green is passed out so deeply that he’s drooling on the sheets. Skinner, she says, acts suspicious.

Krystle Cole: “Hauck’s Scaring Me”

Paranoia and fear is all Cole seems to remember, according to her police statement. Hauck and Skinner, she claims, are both reporting to a federal agency, maybe the FBI or CIA[21]. She overhears them giving out their “agent numbers” on the telephone. She hears Hauck express repeated hopes to kill Green, but he never seems able to “get authorization.” She believes there could be a team of nine other secret agents watching the hotel. She’s not sure what to believe. What if Hauck is a cold-hearted contract killer?

“Hauck’s scaring me. I mean this guy has no emotions,” Cole says in court. “He time and time again said, ‘This is too much trouble. Let’s just kill Brandon and get it over with.’ ”

Skinner intervenes and insists that they should not kill Green, that he was only having a bad trip.

During some point at the DoubleTree, she doesn’t say when, Cole sees Hauck pour a possibly potent drug, salvinorin C, into Green’s mouth[22]. Cole rushes to Green’s side when Hauck leaves the room. He sputters out some of the green stuff. A drop lands on Cole’s arm, turning it entirely numb, she claims. Kristi Roberts shows up and together they put socks and plastic bags on their hands so they can untie and bathe Green without getting the potent chemical on their skin. The rash on Green’s genitals is horrific from all the violent scratching. He has blood and tissue under his fingernails. Cole gets some ice and packs it onto Green’s groin.

The night passes. Green’s penis turns black near his ornamental piercing, the sign of a possible infection. Use antibiotics, she tells Skinner. Hauck and Skinner then shave off all the hair from Green’s body. Skinner injects Green with vitamins and dextrose. Days later, Skinner examines Green again. He believes that gangrene has set in. They wash Green in a bath of Epsom salts, bleach, and chlorine. The fumes, Cole says, were so horrible that she was ill for two days.

Brandon Green: “I Thought We Were Friends”

After July 4, Green recalls very little, but he does have a vivid memory of waking up to the bursting pain of Skinner punting him in the groin.

“You should’ve never touched my fiancée,” he hears Skinner shouting at him, and then everything goes white.

There’s a moment of torture that repeatedly shows up in court records, and if it occurred, it would’ve been before Kristi Roberts showed up to bathe Green. Hauck claims he didn’t see it, adding that Skinner only told him about it. A phone cord is wound around Green’s genitals while he is unconscious. Skinner is allegedly at the other end of the line. He puts a foot down on Green’s stomach, then pulls hard on the cord until the cartilage audibly snaps.

Later, as Green becomes more lucid and Roberts consoles him on the bed, Skinner walks into the room. Green apologizes to him for sleeping with Cole.

“I thought we were friends,” Green says.

Kristi Roberts: “Please Pray for Me”

After caring for Green all night, Roberts eventually fell asleep at the DoubleTree. When she wakes up, Green is no longer there, and she believes Cole and Skinner when they tell her that Green left on his own. She helps clean up the room and discovers a couple of hypodermic needles in the bathroom and becomes even more suspicious of Cole and Skinner. Cole and Skinner decide to pack up and relocate to the Adam’s Mark Hotel a few city blocks away, and Roberts rides with them. From the lobby of the Adam’s Mark, Roberts calls her aunt and asks her to pray because she feels like she’s trapped in a bad situation.

William Hauck: “A Fear of Todd”

These days, Hauck drives a truck from 10 p.m. to 7 a.m. most nights, and he recently pulled over at a rest area to answer some questions about these decade-old events. He gives a plain, chronological account of the kidnapping and doesn’t exaggerate when speaking. He shares Roberts’ perception of Krystle Cole, saying she was clear-headed and lucid during the week-long ordeal. When asked if he saw Cole taking care of Green, Hauck’s answer is flat.

“No,” he says. “She wanted to go shopping. Todd had promised her they would go shopping.”

Much later, after the rooms have been cleaned and Green has been relocated to Hauck’s room, Hauck hears Cole offer a funny idea: Why don’t they shave Green completely bald? Hauck watches as Skinner and Cole lather and shave Green’s head. She applies eyeliner to the edges of Green’s eyelids. Green is so gorked, he doesn’t notice.

“Krystle thought it was hilarious,” Hauck says. “She was shaving off his eyebrows and Todd told me that they had wanted to make him look gay… I was pretty freaked out,” he says. “I knew that I was in pretty deep but there was nothing that I could do because at that point I had a fear of Todd. Todd started telling me how my involvement in everything would link back to my room and this was the only way out—to do it his way.”

Skinner offers a plan to use Green’s own car to dump him. Texas will find him, and they’ll think he had a crazy weekend of partying. On the night of July 8, William Hauck drives the emaciated, drugged, and completely bald Brandon Green to a motel room in Texas City, Texas. Skinner says he and Cole will meet him tomorrow night.

The DEA: “He Sounds a Little Spooky”

The following day, July 9, Skinner is fed up with what he feels is a violation of his immunity agreements, marches into the DEA office in Tulsa with his attorney, H.I. Aston, and asks why the DEA is conducting an investigation of him. In the next 24 hours, a flurry of emails ensues between DEA agents and government officials (pdf 2Mb):

“Can you tell me what this guy [Skinner] was up to?” asks Tulsa Assistant US Attorney [AUSA] Allen Litchfield, a former classmate of Skinner, in an email. “He has popped into DEA claiming all types of immunity etc. Frankly he sounds a little spooky.”

“Skinner was involved in an LSD deal,” Lead AUSA Gregory Hough of Kansas replies. “His attorney got DOJ to give him immunity for his testimony against the other two leaders (Pickard and Apperson). After his testimony in the LSD trial, Skinner flipped back into the arms of his co-conspirators. This precipitated a bunch of mini-trials during our trial wherein Skinner, sponsored by Pickard and Apperson, testified that the three DEA agents, a courtroom deputy, and I all conspired to affect his trial testimony. Skinner alleged that, in spite of our best efforts, he testified truthfully. However, it was a tremendous distraction, likely caused OPR [Office of Professional Responsibility] investigations of all concerned and, at the least was a breach of his immunity agreement… I know three DEA agents, a courtroom deputy, and an AUSA that would love to see him imprisoned and the key thrown away.”

Brandon Green: “He Just Wants Me to Sleep”

When Skinner and Cole arrive at the motel in Texas City on the evening of July 9, Cole thinks that Green has a number of new needle tracks on his arms. Hauck had torn up the bed sheets and tied them around Green’s wrists to keep him on the bed[23]. According to Hauck, Cole tells him and Skinner to do whatever they want to do, but she’s going swimming in the hotel pool. In his confusion, Green continues to think that he and Cole are a couple. He feels ashamed for tripping so hard and apologizes repeatedly from within his stupor.

Skinner gives Green more injections, Hauck says. Skinner then brews a strange herbal concoction. After drinking it, Green feels a swell in his gut like he is about to explode. He vomits into the bathtub. Something wiggles around in the mess. Cole says they look like worm sacks. Hauck sees tiny, translucent parasites writhing around in the bottom of the tub.

The next morning, July 10, Hauck and Cole search for a location where they can leave Green. If he’s left outside, maybe the bug bites will cover all the needle marks. Hauck and Cole return and claim they’ve found an ideal spot to leave Green about a quarter of a mile away.

Inside the motel room, Green lies semi-conscious, with a blindfold over his eyes. Cole tells Green he burned his retinas and that he shouldn’t try to open his eyes. Skinner then pretends he’s a doctor from Sweden who has come to evaluate Green. Outside of Green’s earshot, he explains that he wants Green to have a wholly unbelievable story. The Swedish doctor will make Green a less reliable historian.

When evening arrives, Hauck loads Green into the car and Cole follows him in Skinner’s Porsche. Skinner stays at the hotel and waits.

“I remember feeling safe with [Hauck]. I remember feeling at peace,” Green said of the car ride to the field. “He put his arm over me, and just patted me and said, ‘Just stay there,’ and I fell back asleep.”

En route to the field, Hauck stops at a convenience store and tells Cole to buy water and food for Green. She returns with two bottles of water and some Kit Kat Bites. When they reach the open field, Hauck drives Green’s car off the road about a hundred feet from the roadway and stops. He sets a blanket down on the ground near the car, and then opens the car door to get Green.

“William comes by, unbuckles me, grabs me like a baby and puts me on the grass,” Green said. “I remember thinking, ‘William is so nice. He knows how tired I am. He just wants me to sleep.’ The earth felt really nice. The earth felt really, really, nice, and I just fell asleep.”

Hauck sets the Kit Kat Bites and two bottles next to Green, then climbs into the car Cole is driving. The car pulls away, leaving Brandon Green alone under the Texas night sky, little more than flesh for flies.

Gordon Todd Skinner: “No One is Good or Bad”

According to Skinner, there hasn’t been a fair trial for the Green kidnapping. During the research period for this story, Skinner was able to briefly review a copy of Cole’s book, Lysergic, which contains a number of letters that Skinner allegedly sent to Cole during his incarceration[24].

“I went to the DEA and got you out of trouble,” Skinner reportedly wrote, “you brought Brandon into my life and I got hurt bad. I asked both of you to leave for good—do you remember that??? Not only did I not lure him back to the hotel—I begged you to get him out of my room/life… The two of you should’ve stayed away from me.” The letter goes on to explain how Green and Cole “were sexual” in the hotel bed the first night at the DoubleTree while Skinner slept next to them. “That was wrong, I told both of you,” the letter states.

Today, in his drab prison blues, Skinner carries all the intimidation of your average high school science teacher.

“There was no way anyone could’ve come out alright,” Skinner says. “The only way that anyone could’ve come out decent was if the truth was told, which was that this guy [Green] purely overdosed himself… No one is good or bad. It’s not like it’s that kind of story.”

In Skinner’s estimation of events, the entire week was more sedate than other witnesses recollected. His young children from an earlier marriage visited the hotel room, he says.

Skinner says that the entire Green kidnapping was an elaborate government conspiracy and cites the emails between Hough and Litchfield as evidence. He also contends he was far too ill during most of the Green incident to be as involved as the others allege.

“I had been to the hospital numerous times…” he says. “I was really sick—I just couldn’t coagulate blood. Every hotel room I had, had blood in it.” Green saw Skinner’s nosebleeds, and even admitted taking Skinner to the hospital four times in four consecutive days the week prior to the kidnapping.

Green believes he saw Skinner kick him and yell at him, yet Skinner denies it.

“He also says the most incredible things [in his testimonies],” Skinner says. “But what was going on with him? He was on a massive dose of psychedelics.”

Green’s trauma must’ve been self-induced, Skinner thinks. He says that Hauck is the one who tied Green up, and that he helped Roberts free Green. Hauck does admit to tying Green up, but only in Texas, and Hauck admits to hitting Green as well. Skinner points to Green’s infected penis piercing and his incessant genital scratching as evidence of the self-harm. Moreover, Green was left alone with Hauck for long periods, and Hauck had served time for a sex-related offense, suggesting that the extensive anal damage could’ve been done then.

“I don’t like talking about all this stuff,” says Skinner. “I don’t come from a trashy world, OK? But I’m having to defend myself and everything… This guy [Green] was hell on wheels, for days he was like this.”

Aftermath

Pain is Brandon Green’s constant companion now. It took him months to get out of his wheelchair, a year to begin eating solid foods. Now, 10 years after his kidnapping, his body is riddled with ongoing pain. On a scale of 1–10, with 10 being the most severe pain, Green ranks his neck a 4–6. His shoulders are a 5 on a good day (he still can’t lay on his left side). His hips, pelvis, prostate, and groin hurt so badly that it’s painful to wear pants. Green doesn’t carry a cell phone or wallet because their pressure against his body hurts too much. Bad days are 8s.

“I honestly do not remember at all life without pain; I cannot remember a day I didn’t hurt,” says Green, who abstains from the dulling effects of pain medication.

Work, for Green, is a refuge. He and his wife manage a condominium complex together. Someday, Green would like to begin telling his story publicly. After some of his health returned, in the first few years following the kidnapping, Green returned to a number of illegal activities involving drugs and pimping. He has since disavowed those ways. He’s now a religious man and believes his Christianity has helped him transcend much of the anger, depression, fear, and confusion that could otherwise plague his mind. But forgiveness, for Green, doesn’t mean forgetting.

“I think that Todd is pretty pissed that he did not kill me,” says Green. “You know, knowing Todd, I bet his biggest regret is that he didn’t snap my neck a month prior to the kidnapping. I would love to hug the guy, but I would be afraid he would kill me.”

During the legal proceedings following the kidnapping, the Assistant Tulsa District Attorney David Robertson told Brandon Green that the charges against Krystle Cole would be changed. Cole, Robertson explained, was simply a wayward small-town girl. He parroted the same alibi that Green recalled Cole practicing in the Las Vegas hotel room. Green felt nauseated. The courts amended Cole’s charge to “accessory after the fact.” She pleaded no contest. On March 26, 2007, she was ordered to pay a restitution of $52,109. According to Green, she paid little more than $4,000 and was released from the order.

“I could have fought the case and won,” Cole wrote in Lysergic. “Since I was under duress and basically kidnapped also.”

Bette Brown, the case manager who filed Cole’s 2007 “Finding of Fact – Acceptance of Plea,” pointed out that Cole stayed with Skinner for years, and “does not appear to be someone who is afraid of their spouse.” Brown believed that Cole participated in Green’s kidnapping more than she admitted. Brown recommended incarceration. Cole’s sentence was deferred. Her probation for her role in the kidnapping lasted five years. She served no time.

Cole is now a self-made entheogen expert, just as Skinner had been, but Cole is much more popular. She has created dozens of videos about “responsible drug use.” Her YouTube channel boasts 54,167 subscribers, and at least 10 of her videos have been viewed a quarter-million times each. Throughout her videos and her writings, Cole claims she suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder. She told the court in 2007 that she had no mental health issues.

Cole often presents herself as a survivor, one who has experienced a terrible life event and has moved to a more spiritual understanding of herself and her relationship to Skinner. But, in a 2009 post on her website, Cole claimed she’s tormented by nightmares when she’s reminded of Skinner. Cole also said she had not granted permission to use her name, likeness, book, or life story when we contacted her with questions for this article. Green, seeking closure and understanding, attempted to contact Cole several times in recent years, to no avail; she replied to Green’s messages soon after hearing from us. She convinced him, for a short time, that she tried to rescue him during the kidnapping. “Honestly, I believe you,” Green wrote in an email to Cole. Cole then asked Green for his permission to publish their email exchange (with her edits) on her website. Then Green heard Hauck’s version of the events. He felt once again betrayed by Cole.

“How could I be so gullible?” he asked.

If Green senses that justice has not been served, it’s in the matter of Krystle Cole’s involvement.

“Krystle should be in jail,” he says. “I feel like Todd is on the last end of his crazy life, but Krystle is at the very beginning of it. Krystle has been trained by the very best. I would feel more comfortable with Todd being out of jail than Krystle staying free…. I feel like Todd’s ceiling is Krystle’s floor. That is why I feel like she is more dangerous. I feel like she was able to consume everything Todd had, then pushed him out of the way and continued going.”[25]

For his willingness to testify against Skinner, William Hauck’s charges were amended to “accessory after the fact.” Hauck is a barrel-shaped man, with gray hair and a goatee. Since testifying against Skinner, he claims there’s been two attempts on his life. He found bullet holes in the side of his truck one morning; on another, a gas can was wired to his car.

On Sunday, June 16, 2013, Green and Hauck reunited. It was the first time either of them had spoken or seen each other since the trial. Hauck was apprehensive at first. Upon arrival, Green hugged Hauck without a word.

“If I were you,” he told Green, “I would’ve brought a big gun to this meeting.”

Green told Hauck that he’s forgiven him and moved on with his life.

“For a long time, even after the trial, I couldn’t sleep,” Hauck said. “I couldn’t look at myself in the mirror. I wasn’t only embarrassed, I was ashamed.”

“Why didn’t they actually kill me?” Green asked him. “Because it would have been better for them to just kill me.”

“At that time, I was involved in it, and that wasn’t going to happen,” Hauck said. “I mean, dumping you off in the woods and letting you find your own way out was one thing, but killing you was—I would have picked up the phone at that point.”

Hauck answered all of Green’s remaining questions for over two hours, filling in gaps and questions that Green carried, many of them having to do with Krystle’s behavior during the kidnapping. At the end of the questioning, Green told Hauck that he hoped he might find the strength to forgive himself.

“Even if I were able to forgive myself,” Hauck replied, “I would never be able to really forgive myself.”

William Leonard Pickard is appealing his case while serving life imprisonment in Tucson, Arizona. He contends that he was the victim of a con orchestrated by Skinner. In 2005, Cole filed an affidavit with the U.S. Court of Appeals stating that Skinner owned the Wamego lab equipment, Skinner was in fact the chemist, and Skinner told her that he planned to setup Pickard up as the responsible party in the LSD operation.

“This is what you do when you get hot,” Cole says she heard Skinner say, “you turn the other people in before you get busted.”

Pickard is now 67 years old. Outside of his legal filings, he primarily reads literature published between the years 1840 and 1920. He actively updates the site freeleonardpickard.org and uses student volunteers to facilitate his email communication.

During their respective appeals process, Skinner’s and Pickard’s attorneys have maintained occasional communication. Pickard claims to have met Cole on only one occasion, and has not read her book. Cole’s actions have done little to help his situation.

“She is also deleterious to the case by promoting her various fantasies, derived largely from her brief marriage to an unreliable informant, or from her scrutiny of documents concerning sophisticated interactions about which she has little experience in interpreting,” Pickard wrote from prison. “Some feel she frantically is scrambling to some peak of notoriety in the absence of other distinguishing accomplishments. We, as observers, are saddened…The spectacle of Cole commenting on the case to her profit, eagerly filling a void that has not yet been addressed by the principals, is rather as if Judas’s wife was the sole public source of information on the Crucifixion.”

In an odd turn of events, Pickard has recently been calling Brandon Green, with the explanation that he would simply like to be friends. Green enjoys the calls, he says.

In June of 2006, a jury found Gordon Todd Skinner guilty of kidnapping, assault, and conspiracy of kidnapping. The jury sentenced Skinner to life for the assault charge, and 90 years for kidnapping and conspiracy; Skinner was already incarcerated at that point for drug-related crimes concerning activities at a Burning Man festival. Skinner claims that his immunity agreements were violated when the DEA cooperated with the Tulsa Police Department’s kidnapping investigation of Skinner.

“Who cares about the DEA hating you?” he asks. “That’s like a badge of honor if those guys hate you because it means you must have done something right.”

From the letters in the back of Lysergic, it appears that Skinner has formed new spiritual understandings while incarcerated. One letter states:

The Brotherhood of Eternal Love and its ilk were another spiritual con game. These people in the Network were there for the money—I used to say gift everything to prove your point. LSD Network was a high class drug Network—but money (MAMMON) oriented—Not Spiritual—but do not teach each one how to be their own Priest? Just a power game…Do you think I have gained wealth, fame or power from this road? I bow and pray each day and remember the True Sacrament of life is LOVE.

Skinner is still technically married to Krystle Cole—for legal reasons, he says. He plans to sign the divorce papers soon. He claims he doesn’t feel betrayed by Cole, not exactly.

“I mean, it wasn’t betrayal,” Skinner said. “She was involved in a massive conspiracy that went on for years and she admits to it.”

He’s not the kind of guy who has regrets, he says, but he clearly feels the pain of imprisonment. He continues to file appeals outlining the various injustices he claims he’s suffered at the hands of the DEA and government officials. Should the appeals be unsuccessful, Skinner’s earliest hope for parole would be when he’s about 80 years old.

“I’ve spent ten years of my life—my life’s been threatened, I’ve been greatly harmed, I have lost everything, and the paper trail is overwhelming of what has been done to me,” he says.

The trail of what Skinner has done to others is stacked just as high. Both of those trails converge behind the gray walls of Joseph Harp Correctional Center, Skinner’s home. Unless a new trail appears, Gordon Todd Skinner remains trapped in the worst trip he has ever taken.

Endnotes:

1. Journalist Dan Casey of the Roanoke Times claims to know Sand. Casey says Sand told him Pickard had contributed to Sand’s defense by donating a painting. Pickard claims he is not personally acquainted with Sand and did not contribute to either his 1973 or 1996 proceedings.

2. Regarding the case, Pickard writes: “The 1976 charge: the defense position was that the lab equipment was derived a job repairing same at a recycling firm. I was held 4-1/2years without a plea, then released on the same day in exchange for said plea, in this instance, nolo contendere, or no contest. The time served was the maximum under California state law, minus good time.”

3. According to Skinner, Magrini was later assigned to the IRS as a special agent. According to freepickardonline.org, Magrini was assigned to the DEA in 1984.

4. Federal Bureau of Investigation, Drug Enforcement Agency, Internal Revenue Service, and U.S. Customs and Border Patrol.

5. Psychonauts split hairs, arguing that Ecstasy [MDMA] is actually an empathogen, which enhances feelings of oneness between people rather than between the self and the universe.

6. From “Soma,” by Stephen Naylor in Encyclopedia Mythica: “Though he is never depicted in human form, Soma obviously did not want for lovers; poets rarely do. In one episode, his desires caused a war. He had grown arrogant due to the glory that was offered him. Because of this, he let his lust overcome him; he kidnapped and carried off Tara, the wife of the god Brihaspati. After refusing to give her up, the gods made war on him to force her release, and Soma called on the asuras to aid him. Finally Brahma interceded and compelled Soma to let Tara go. But she was with child, and it ended up that this child was Soma’s. The child was born and named Budha (not to be confused with the Buddha).”

7. Around 1987, Skinner’s mother, Katherine Magrini, owned a candy shop where she sold a delectable she called “Okie Power.” She was reported to have sold this enterprise to Boris Olarte. According to Leonard Pickard’s timeline, Olarte’s wife, Clara Lacle, was residing with Magrini. Lacle flew to Aruba with FBI agents to set up Olarte’s supplier Abello Silva.

8. According to a DEA report dated 7/31/2003, Hauck stated he had been jailed for having sex with his 17-year-old sister-in-law. He was charged in December of 1989 for a criminal sexual act in New Jersey.

9. Throughout the literature on Pickard and Skinner, this conference is often mistakenly referred to as an “ethnobotony” conference. An article from the San Francisco Chronicle indicates that this conference is the first time Skinner and Pickard met. Pickard’s timeline suggests that they met later, in February 1998, at a chance encounter in a San Francisco hotel lobby where the chemist Alexander “Sasha” Shulgin was speaking. Skinner claims that Pickard was wheeling around $700K in cash in his luggage bag at the time, claiming he was being followed.

10. “I had two Clydesdales, three miniature horses, one miniature donkey,” Skinner told a courtroom. “And the llama herd expanded and contracted over time, so I can’t give you an exact number of hoofed, even though they would not be classified, quote, hoofed animals, the llamas, but let’s say between two and eight.”

11. Skinner claimed he kept a group of lower-level staff who would exchange moneys at casinos and elsewhere. One of the operation’s logistical strategies involved unloading huge volumes of Dutch guilders into the Las Vegas market—a tricky feat, as the guilder was simultaneously depreciating. Pickard and Skinner were moving so much cash at the time, Skinner says, that they wouldn’t bother to account for transactions under $30,000. He says they refused to use any bills less than $20 on the grounds, that lesser currency took up too much space.

12. Skinner’s account of moving the lab is dramatic: He calls Pickard in London who warns him not to move the lab, and Pickard even says he’s taking the next flight in. Skinner tells him there’s no time. He rounds up several friends, along with his biological father, Gordon H. Skinner, to retrieve the equipment. When they enter the silo, they discover that the lab is in shocking condition: it has standing water in it, with electrical cords and toxic trash floating in the area. The chemical odor was powerful, yet the group still risked heavy exposure to dangerous chemicals in order to move the lab. One friend, Gunner Guinan, was heavily exposed to LSD, and Skinner said that there were “32 to 36 hours of not being able to communicate with him.” All in all, it took three days to disassemble and move the lab. Skinner returned the keys to the Atlas-F silo with three hours to spare. Clyde Apperson showed up soon thereafter, claiming he was in the hospital with a viral ear infection and agreed that Skinner had needed to move the lab.

13. Skinner says that federal agents later told him the informant had not been killed after all.

14. Later, the DEA learned that the precursor that was found at the silo was ergocristine, which was then uncontrolled.

15. At a coffee shop, Savinelli received a note that he perceived as a death threat, and he surmised that note came from or through Pickard.

16. During a tour of the Wamego missile silo, the current owner stated that in 2006, someone broke into the silo, tore through some specific tiles in one of the bathrooms, and reclaimed “who knows what” from the hiding spot.

17. In a 2006 cross-examination, Cole stated that she had gone to Oakland, California, at some point in her past and met with DEA agents. She was unable to recall when or how she got there. It may have been following the Nevada trip with Green.

18. Cole claims that she left Green because Skinner threatened to report her and Green to the DEA and that they would then face life imprisonment. Cole also claims that Skinner was aware that she and Green had spoken to the DEA by that point. According to Green, however, Cole called Skinner of her own volition, as they did not take cell phones with them to Las Vegas; this, of course, implies that Cole never really intended to escape Skinner. Skinner also claims that Cole called him and told him she wanted to get married. Green also recalls that the reason Cole told him she was going to California was to meet with members of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love to get false passports. Green claims he looked upon Cole as “his boss” and simply assumed she was in charge of their getaway.

19. Cole claims that when she returned from Vegas, Skinner dosed her and kept her drugged, and that he threatened her into marrying him—a story she has recounted in her book MDMA for PTSD. During her cross-examination, though, she did admit to being engaged to Skinner for a couple of years prior to the wedding but she was not planning to marry him.

20. Skinner believes that the reason Green was interested in hanging around was so that he could inform to the DEA about Skinner’s activities. Green had recently been arrested on a drug charge in Lebanon, Missouri.

21. Hauck says that Skinner would ask him to pretend to be a secret agent in front of Cole, and he went along with the ruse without really understanding why.

22. Salvinorin is the psychotropic molecule in the natural hallucinogenic plant, Salvia divinorum. According to a 2001 report by the American Chemical Society, salvinorin C is reportedly inactive when taken by mouth. Court records suggest that Hauck was not present when Cole and/or Skinner gave Green the salvinorin.

23. Hauck claims that Skinner gave him a syringe to use in the event Hauck needed to sedate Green, though he denies ever using it.

23. Skinner believes the letters may have been augmented, but he has not been able to fully review the book.

24. In 2011, Cole acted as the primary government witness against one of the advertisers on her website, Clark Sloan, an individual who was allegedly selling illegal substances. He was indicted with twenty drug-related counts.

© 2013, THIS LAND PRESS