Gaudy Liar

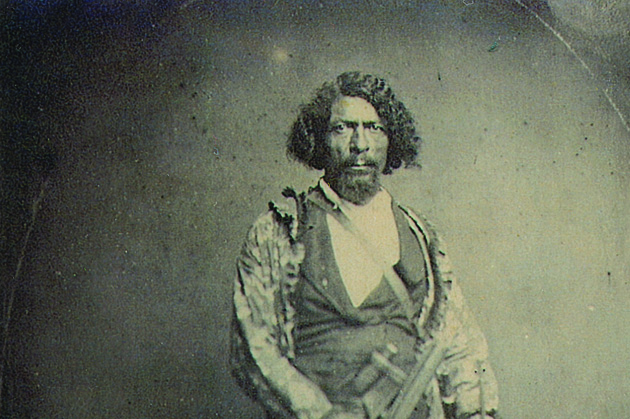

In 1856, the appearance of the action-packed Life and Adventures of James P. Beckwourth, Mountaineer, Scout, and Pioneer, and Chief of the Crow Nation of Indians offered the first published account of the escapades of a black man in the American West. In the goldfields of California, Beckwourth dictated his rousing life story to T.D. Bonner, an itinerant justice of the peace, journalist, and temperance advocate with a drinking problem. The book was an immediate success. It was released in England later that same year, followed by a second U.S. printing and a French edition in 1860. While much of the public eagerly devoured the tales of high adventure among the Indians, others, in that time of blatant racism, dismissed the book as the musings of a “mongrel of mixed blood.” Critics pointed out that among his fellow mountain men, Beckwourth was jokingly referred to as a “gaudy liar.” But later historians, such as the acclaimed Bernard DeVoto, reassessed Beckwourth and found that much of what he described actually happened. They also pointed out that to be a “gaudy liar” among mountain men was actually a compliment, since exaggerated tale spinning was a skill as valued as marksmanship and tracking. Beckwourth’s autobiography remains the best account of several Indian tribes in the first thirty years of the nineteenth century.

Bass Reeves

One of the most feared deputy U.S. marshals in Indian Territory during his thirty-two years of service, Bass Reeves was born a slave and died a hero. Reeves, the first black federal lawman commissioned west of the Mississippi, had fled Texas as a fugitive slave during the Civil War. He settled in Indian Territory and in 1875 was hired to ride for Judge Isaac C. Parker, when the “Hanging Judge” first took the bench in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Reeves became fluent in Creek and several other Indian languages and was a master of disguise, a talent he often employed when pursuing criminals. He also was ambidextrous and could shoot a pistol with great accuracy using either hand. At a time when unconcealed racism was widespread, the physically imposing Reeves won the respect of his fellow deputies and even some of the outlaws he tracked down and brought to justice. He reportedly apprehended the largest number of fugitives of any of Parker’s lawmen, pursuing such infamous outlaws as Ned Christie and Belle Starr, who turned herself in after learning that Reeves had a warrant for her arrest. Reeves sported fourteen notches on his six-gun, but despite having many close calls of his own, he was never wounded. He was, however, wrongly charged with murder in the accidental shooting of his camp cook, but won an acquittal. In 1902, the aging lawman arrested his own son for the murder of his wife, and the young man was sent to the federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas. In Reeves’s book, no one was above the law.

Dusky Demon

There never was another cowboy quite like Bill Pickett. This black wrangler, who endured extreme racial prejudice, invented bulldogging—the only rodeo event ever originated by an individual. Pickett’s style for bringing down a steer was unusual. He would leap from his pony, Spradley, on the steer’s back, grab a horn in each hand, and dig his boot heels into the ground. After twisting the critter’s head to bring up its nose, he chomped his teeth on the cow’s tender lip and fell backward causing the beast to fall down. With flair, Pickett threw his hands into the air to show the audience that he no longer needed to hold the horns. Billed as the “Dusky Demon,” Pickett signed on with the Miller Brothers’ 101 Ranch in 1905. He rode with them as both a performer and cowhand until his death at age sixty after he was kicked in the head while tanning an unbroken chestnut gelding. Will Rogers spoke of his passing on national radio. More than one thousand people gathered on the ranch for Pickett’s funeral. He was laid to rest on a windswept hill, not far from where his beloved Spradley was buried. For the rest of his own life, Zack Miller looked folks straight in the eye and told them, “Bill Pickett was the greatest sweat-and-dirt cowhand that had ever lived—bar none.”