The Tulsa Underground Circus fictitiously wrote that it was the work of a deranged Russian immigrant, a circus clown trained at the Moscow Circus School. The day before the catastrophe, during a routine inspection of the show’s equipment, the fire marshal found disturbing evidence that he felt required legal interrogation. Within several of the trunks were sheaths of human skin and a cadaver with a paper maché face. He cancelled the group’s impending Coliseum debut, locking up all circus possessions inside the building, throwing the Russki into a rage. Some say he perished in the fire; perhaps he returned to Siberia. Either way, he disappeared. Smoke and mirrors were no strangers to Tulsa’s Coliseum.

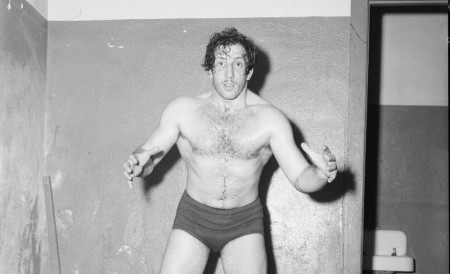

In the golden age of “Killers” and “Stranglers,” “Gorgeous George” Wagner was professional wrestling’s pretty boy. Wagner had a Ph.D. in psychology and a valet that would disinfect the ring—spraying it with perfume and sprinkling rose petals across its mat—before curly, blonde Gorgeous would make his entrance, stepping through the ropes like some Liberace of the turnbuckles. He was a taunted coward whose shtick made him rich and famous in a Tulsa landmark known as the Avey Coliseum. In the 1940s, wrestling in Tulsa was a wildly popular attraction, with crowds cramming, jamming the art deco Coliseum—it sat a few blocks from the BOK, where today the WWE holds similar court—and Wagner was part of a stable.

Cavernous and decadent, the memory of the building is shared by few. Tulsa developer and politico Sharon King-Davis, a granddaughter of Avey, recalls going to a midget wrestling card as a young girl with her mom, Pat, who shared a 50-50 ownership of the building with her dad, Sam Avey. Sitting on the front row when the smaller-size gladiators wildly pulled themselves through the ropes and onto the mat, the crowd erupted and she remembers, “I was so scared, I ran up the aisle and wouldn’t come back.”

Avey, a native of Kingfisher, traveled six years in the 1910s with vaudeville companies learning how to put on a show. With the popularity of professional wrestling on the rise, the sport seemed like a sure bet. Shortly after World War I, Avey went on tour as a referee for the successful promoter Billy Sandow.

Armed with his insider knowledge, Avey moved his family to Tulsa in 1924 to launch a new venture for Sandow. With the prowess of the Oklahoma A&M wrestling program, the state had become a mecca for aspiring wrestlers. But there was nowhere to stage matches.

In the mid-’20s, a Minnesota native named Walter Whiteside founded the Douglas Oil Company with money he made as a lumber mogul in Washington state and British Columbia. But Whiteside had dreams beyond liquid gold. With F. S. Stryker, he formed the Magic City Amusement Co. and, in 1928, built an indoor arena on the west side of Elgin Avenue extending the entire block from 6th to 5th streets.

Designed by architect Leon Senter—whose projects include Skelly Stadium, Booker T. Washington High School and St. John Hospital— the 7,500-seat brick and terra cotta edifice was the largest show palace of the Southwest. Its floor could be iced over in eight hours, making it the region’s first indoor skating rink, the primary interest of Whiteside.

The Coliseum opened on New Year’s Day, 1929, with the Tulsa Oilers playing their first American Hockey Association game against the Duluth Hornets, thus accomplishing Whiteside’s goal of establishing the city as the southern-most frontier of professional hockey. Interestingly, the Hornets were the first athletic club sponsored by Whiteside and his father in their hometown of Duluth. Sam Avey, watching from a different set of sidelines, had his eye on the new venue for a different sort of sport.

The Depression came and wiped out Whiteside’s thriving empire. His holdings, including the Coliseum, went into receivership for a decade. Then, in 1942, creditors formed the Coliseum Company and bought the property in a sheriff’s auction. Tulsans—war-torn and downtrodden—took heart.

Avey claimed he had to pawn his favorite shirt and go deeper in debt than he liked when he purchased the Coliseum for $185,000 in 1942. The electric organ continued to pump out the “Skater’s Waltz” as thousands learned to ice skate and locals packed the house to hear Nat King Cole. But nothing drew crowds like the shirtless men in tights.

Doing what he did best, Avey popularized Monday night wrestling long before Howard Cosell, Frank Gifford, and “Dandy” Don Meredith proved America was ready for some football. With its outlandish personalities and questionable ethics, wrestling was all the rage. Avey promoted his favorite arena-filling star, Leroy McGuirk.

The former Oklahoma A&M standout became the U.S. Junior Heavyweight wrestling champ. Professional wrestlers flocked to the Avey Coliseum for a chance to take down McGuirk. The pro circuit hit the road, largely in the South. During a trip to Little Rock, McGuirk was blinded in a car wreck. Rather than abandon his franchise, Avey put McGuirk in the post of matchmaker and gave him a stake in his Tulsa-based promotion company.

The Coliseum welcomed the likes of Killer Kowalski, Ed “Strangler” Lewis—a beast of a man with big, black bushy eyebrows and monstrous hands, and a thick neck out of proportion to his super-sized head—and a local yokel named Farmer Jones. Weighing in at over 300 pounds, this Arkansas native in single-strapped overalls said to Frank Morrow of KRMG radio, “Once I git on top of ’em, they ain’t goin’ far.” Yet the pleasinest’ crowd pleaser of them all was Al “Spider” Galento.

The “Spider” would wrestle all comers—$1 for each minute you could stay in the ring with him and $100 if you won. Occasionally, Galento would become frustrated with his opponent and pummel him in the face, an illegal action that drew hisses and a dismissal. Celebrating the unexpected victory, the bleacher bum staggered off the mat, waving the C-note. The cheers and jeers that followed him out would not echo for long.

At 9:31 p.m. September 20, 1952—a Saturday—a three-alarm fire sent eleven fire trucks to a blaze engulfing the Coliseum.

Ray Murphy, living in an apartment directly across the street from the Coliseum, told television and newspaper reporters that just moments before noticing the fire on top of the building, he saw a lightning bolt flash above the structure. It had not rained for 25 days and the wooden roof was dry as kindling.

The night watchman was due to report at 10, which meant only two people were in the building as it went up in flames.

KAKC, an Avey-owned station, had set up its studios in the building’s basement. In its soundproof catacombs, DJ Bob Griffin, a University of Tulsa freshman, and chief engineer M.M. Donley were monitoring a broadcast of the Mutual Radio Network, having switched from the rain-cancelled stock car races at the Tulsa Fairgrounds. Water from the fire hoses gushed through the soaked ceiling. Griffin climbed the stairs to the street.

Seeing the fire, he rushed back to the control room alerting Donley, but not the listening public, to the fire. Forced by officials to vacate, the two transferred the transmission of the program to a support facility. Moments after they reached 6th Street, the wooden roof and its supporting girders collapsed, pulling down much of the exterior walls.

KAKC manager Jim Neal called Avey, who was attending a house-warming party for his only daughter. Rushing to the scene, he could not bear the sight, saying to a Tulsa World reporter, “I’ve had too many happy memories in that old barn to want to watch it die.” He returned to his home at 16th and Gillette.

Turning on the black-and-white television, Avey and his wife tuned into Channel 6. Located only two blocks from the Coliseum, KOTV had set up a camera on the roof of their building and broke into regular programming four times to show the progress of the fire. A stunned Avey sat in front of the tube as the most popular 10:30 p.m. Saturday night show began—ironically, a film of wrestling matches that featured a four-man, tag-team event in Chicago. “I guess I looked at it,” Avey told the World, “but I don’t even remember it. I was too dazed.” He wasn’t alone.

Among the estimated 12,000 who quickly gathered to watch the inferno was Tulsa’s future hamburger Nazi, J. J. Conley, and his father. Conley remembers his father, who manned the Coliseum lighting system, saying, “Son, you are watching my job go up in smoke.”

Fire Marshal Farl Wagner said to the Tulsa Tribune, “Presumably, lightning struck the southeast corner of the roof. The wooden roof burned quickly.” Within two hours there was only rubble.

Avey had a $300,000 insurance policy for a building that architects, several years earlier, claimed would take nearly $1.5 million to replace. Following the adjuster’s report and settlement, the building was razed and has been a parking lot ever since. Two years ago, daughter Pat petulantly sold the lot to the East Village development consortium and along with it the sentimental remnants of the Tulsa icon that towered over that parcel of land.

A timepiece and a musical instrument were the only coliseum survivors. The precision master clock that provides timing signals to synchronize the building’s network of slave clocks was being repaired off-property. It resides in the Tulsa Historical Society lobby.