Little Rock was shell-shocked. It was July of 1960, and in the past year, five bombings had terrorized the city’s public school system. The state legislature of Arkansas attempted to thwart desegregation by shutting down Little Rock’s public high schools, but the bombings sent a far more violent message to the city’s pioneering civil rights community. Similar incidents throughout the South grabbed the country’s attention, forcing the Federal government to intervene. In Arkansas, the government put a zealous Army general in command of the military district to ensure safety and integration.

Federal Bureau of Investigation agents combed Arkansas for suspects in the bombings, and they were looking for one man in particular: a high-profile segregationist preacher from Oklahoma named Billy James Hargis. According to FBI special agent Joe Casper, Hargis was planning to bomb the Philander Smith College in Little Rock soon. The preacher had recently met with two other bombing suspects at a Memphis restaurant.

“We ought to get a permissive search warrant from him [Hargis] to search his home, car, and any outbuildings at his residence,” Casper suggested. “We have evidence that these people we have arrested in Little Rock have been in contact with him.”

The FBI had cause to be concerned. Hargis’ tirades mirrored those from any number of early 20th century Ku Klux Klan pamphlets. He was anti-communist, anti-union, pro-segregation, and he preached those values on a 15-minute daily radio show that aired on stations throughout North America. Based in Tulsa, The Christian Crusade was the public name of Hargis’ media empire, one that included a magazine, the daily radio program, Christian Crusade Publications, and a pioneering direct mail operation that expertly distributed Hargis’ propaganda throughout the world. By 1960, Hargis had the ability to martial sizeable crowds and stir them with his incendiary speeches. In the eyes of the FBI, he was a serious threat; in the minds of many Cold War Americans, though, Hargis was a new kind of patriot.

Crusading for Purity and Essence

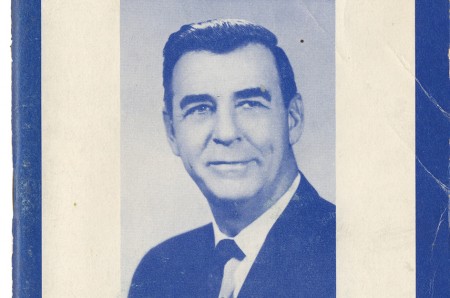

Before anyone heard Rush Limbaugh infiltrating AM radio, before televangelists like Pat Robertson and James Dobson organized the Christian Right, before Tea Party favorites Rand Paul and Paul Ryan began their campaigns, there was Billy James Hargis. Born in Texarkana, Texas, in 1925, Hargis was raised in poverty during the Great Depression and at an early age decided to commit his life to Christianity. Clean-cut, chubby, and baby-faced, he looked like a Kip’s Big Boy statue come to life. By the age of 22, Hargis had become a religious renegade. After a brief stint as a pastor in Sapulpa, Oklahoma, he married a woman named Betty Jane and in 1948 started his own religious non-profit, Christian Echoes Ministry, where he began preaching against communism.

Anti-communism wasn’t a new message in Oklahoma; as early as 1917, with the start of the Bolshevik Revolution, civic organizations like the Tulsa Councils of Defense, [1] in conjunction with local publications like the Tulsa World and Tulsa Tribune, contributed to an atmosphere of repression and paranoia, now known as the Red Scare. But it was the strong presence of the Invisible Knights of the Ku Klux Klan in Oklahoma that made anti-communism an integral part of the Protestant faith—the Klan opposed Catholicism and Judaism as much as it railed against communism. [2]

The KKK took their symbolic cues from the Christian crusades of Medieval Europe—knights, white robes, and fiery crosses—and they borrowed the terminology of the period. They called themselves the Invisible Empire, Knights, Dragons, and Wizards. By the time Hargis was a young man in the late 1940s, the Klan was in its decline in Oklahoma—but its potent mix of segregationist ideology, Evangelical Protestantism, and anti-communism found a champion in the gifted young evangelist.

During the early part of the 1950s, Hargis traveled the country, lecturing on the many conspiracies facing americans, like communist infiltration and fluoridated water. Hargis’ Christian Crusade floundered at first, until Hargis came up with a flamboyant plan in 1953: He would take Bible verses, tie them to tens of thousands of hydrogen-filled balloons, and launch them from Chalms, Germany, with hopes that the balloons would land over the Iron Curtain. His idea managed to attract the support of the International Council of Christian Churches, [3] which helped fund and realize the project. The ICC’s support of Hargis brought him onto the world stage of an emerging post-war phenomenon, right-wing evangelism. Hargis was now poised to become the spokesman for a new movement that fused American politics with fundamentalist Christianity.

No Fighting in the War Room

Hargis’ crusade found many allies, but it was his collaboration with one man that proved to be a catalyst for the formation of America’s religious right. A West Point graduate, Major General Edwin “Ted” Walker was a WWII army hero and leader in the Korean War. In 1957, Walker found himself in command of the Arkansas Military District in Little Rock, just as the city’s civil rights tensions were escalating.

As president Eisenhower prepared to use Federal troops to enforce the desegregation of Little Rock’s public schools, Walker was protesting the matter directly to Eisenhower; he opposed racial integration. Nevertheless, Walker followed Ike’s orders and ended up receiving national praise for helping to integrate Little Rock; a 1957 cover of Time magazine portrayed him as a hero. Walker would later state that he led forces for the wrong side in Little Rock—he believed black students had no business attending white schools.

Before the integration of Little Rock, Walker was a garden-variety anti-communist, but when the incident at Little Rock propelled him into the political spotlight, he became radicalized. The same year, both Billy James Hargis and Texas oil tycoon H.L. Hunt were bombarding Arkansas radio waves with their rightist sermons—programs that aligned completely with the position of Senator Joseph McCarthy, who believed communists had infiltrated the U.S. government. [4] Hargis, however, advanced McCarthy’s views even further, and preached that the civil rights movement was itself a godless communist plot.

In 1959, when Walker was still in command in Little Rock, he met with a conservative publisher named Robert Welch, who had recently founded the John Birch Society on the premise that Eisenhower was in reality a communist. [5]Walker, primed for years by Hargis’s radio rants, joined the society and turned against the government. He attempted to resign from the Army citing concerns over communist encroachment in the U.S., but Eisenhower refused Walker’s resignation and instead promoted him to the position of Commanding General of the 24th Infantry Division.

Convinced that his commander-in-chief was a dreaded communist, Walker nevertheless agreed to accept Eisenhower’s offer. In October of 1959, Walker took command of 10,000 troops in Augsburg, Germany. Now at the height of his military career, Walker devised a plan to propagate his views to U.S. servicemen who trusted his leadership—views that came directly from the teachings of the John Birch Society and the Christian Crusade.

While Walker was commanding his troops in Europe, the political landscape in America was changing drastically. John F. Kennedy was the embodiment of everything Walker hated and feared: he was Catholic, he was liberal, and he was sympathetic to the United Nations. Camelot—as Kennedy’s presidency came to be known—was, in Walker’s eyes, evidence that the U.S government had succumbed to communism. Kennedy was sworn into the office of the presidency on January 20, 1961, just as Walker was establishing the guidelines for the strict regime that would govern his troops.

“Within my authority and within the requirements of training necessity, I devised an anti-communist training program second to none—called ‘Pro Blue,’ ” Walker wrote in a memoir. “Equally important—I organized a Psychological Warfare section with the Division to extend the Pro Blue Program through six echelons, to include every officer and soldier—chaplain, medic and rifleman.”

Established as an official U.S. Army project in January of 1961, the Pro Blue Program was the result of Walker’s fear and paranoia about communism; the official plan was turgid with reprogramming techniques. Under the Pro Blue Program, troops of the 24th Division were required to participate in a series of indoctrination methods that included publications from the John Birch Society and supplied by Hargis. Service members and their families were required to participate in 11 different special activities, including a six-hour training session involving “communist techniques,” the Freedom vs. Communism program, the Freedom Speaks program which offered lectures from Pro Blue writings, and the Ladies Club and NCO Wives Club, which were discussion groups featuring guest lectures on anti-communism.

In 1961, the threat of communism came within 90 miles of America. Publicly, the Cuban revolutionary Fidel Castro insisted that he was not a communist, but Cubans themselves began revolting against his socialist reforms. That spring, Communist countries came to Cuba’s aid and squelched a U.S.-backed attempt to overthrow Castro’s regime. The incident, known as the Bay of Pigs, cemented America’s fear of Soviet encroachment, and that fear was promulgated through the upper echelons of the Department of Defense. Walker’s Pro-Blue program confronted the threat of communism directly and aimed to “produce tough, aggressive, disciplined and spiritually motivated fighters for freedom.”

The Pentagon admired Walker’s program and planned to promote him to Lieutenant General in command of the 8th Corp in Texas.

“Dear Ted,” wrote the Pentagon’s Major General William Quinn, “One of our basic philosophies is that Commanders should tailor their troop information to their own ideas and needs. That is why we have followed the progress of your Pro-Blue with interest and with pleasure.”

The intended promotion, however, never arrived. In April of 1961, a military-themed magazine The Overseas Weekly published an investigative report that detailed Walker’s distribution of John Birch Society literature to the troops—readings that contained inflammatory material questioning the presidency and U.S. government policies.

A media controversy ensued. [6] Some outlets criticized Walker for his extreme views and suggested that military commanders had no business plying their troops with political propaganda; conservative outlets balked that politicians were muzzling the military. Finally, President John F. Kennedy himself weighed in on the matter:

“The discordant voices of extremism are heard once again in the land—men who are unwilling to face up to the danger from without are convinced that the real danger comes from within. They look suspiciously at their neighbors and their leaders. They call for a ‘man on horseback’ because they do not trust the people. [7] They find treason in our finest churches, in our highest court, and even in the treatment of our water. [8] They equate the Democratic Party with the welfare state, the welfare state with socialism, and socialism with communism. They object quite rightly to politics intruding on the military—but they are anxious for the military to engage in politics.”

The Pentagon responded to political pressure by relieving Walker of his command and transferring him to Germany. It would not be the last time a Kennedy angered General Walker.

“When the administrators of federal government serve a higher world government or a doctrine not provided by the people and the Congress, there is no Constitutional President,” Walker later reflected in a small booklet. “With no President, there is no Commander in Chief of the U.S. Armed Forces. I resigned.” [9]

Walker left the Army on November 4, 1961. Instead of seeing it as the end of his career, he sensed America was ripe for a political insurgency, and that he could help bring about a revolution of his own, one that did not include communists or atheists. While in the military, Walker enjoyed the support of countless personnel to help disseminate his ideas. Now, with political aspirations in mind, he sought the support of an organization that aligned with his sense of Americanism and anti-communism. He needed the Christian Crusade.

The Christian Crusade Gets on the Hump

In 1951, the Harvard Business Review published a quiet yet peculiar essay by a business executive for James Grey Incorporated. In “Direct Mail Advertising,” Edward Mayer outlined a persuasive argument for bombarding the American public with mail solicitations—a predecessor of email spam techniques. It was an early day manifesto that would eventually become a cornerstone of the Billy James Hargis empire. Using direct mail marketing, Hargis began asking for small donations to be sent to his ministry in Tulsa.

Throughout 1950s and early ‘60s, Hargis’ Christian Crusade built momentum. During that period, Hargis hired a promising young Texan named Richard Viguerie. Armed with a keen understanding of databases, Viguerie devised mass mailings targeting donors who were likely to be fundamentalist separatists—the kind of people who would respond to antics like Hargis’ balloon drops. With Viguerie’s genius, Hargis reached a widening audience, but the Christian Crusade still needed an overall strategy that would propel it toward success. It was around this same time that Hargis met a publicist named Pete White, who had once helped the televangelist Oral Roberts build a successful ministry through the manipulation of mass media. By using the same strategies used by Roberts, combined with Viguerie’s direct mail ingenuity, Hargis’ Christian Crusade rocketed from a small operation to a ministry that had “billings from $400 to $500K a year in 1963.” [10] During this time period, Christian Echoes Ministry mailed an average of 2,000 letters every day—many of those letters returning with a dollar or two stuffed in the envelope.

“Ours is purely an educational program,” Hargis told the Tulsa Tribune from his Boston Avenue office decorated with gold-sprayed Joan of Arc statues. “We have the most extensive files anywhere on this matter of communism and we are trying to get that word to the people.”

Hargis became more adept in rightist political rhetoric, which began earning him a national reputation as a conservative leader. In 1959, a Chicago-based organization called We, the People, designated Billy James Hargis as its president. Founded by Henry T. Everingham to support conservative politicians, We, the People produced pamphlets promoting anti-communism and criticizing integration. In 1962, the organization held its first “T-Party” rally which aimed to end the “taxes, treason, and tyranny” of the political left. At that time, Hargis stepped down as president, ceding the position to Mormon leader Ezra Taft Benson, who referred to America’s South as a “Negro Soviet Republic.” Benson later served as president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints. [11] Today, We, the People stands as one of the earliest collusions in conservative politics between Christians and Mormons.

As the Christian Crusade ministry increasingly reached into mailboxes and across airwaves, its message became more threatening to the civil rights movement. The FBI questioned Hargis over his involvement in the Arkansas school bombing plot and continued to monitor his activities. Hargis told his followers that the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was a communist plot; he published a book called The Negro Question: Communist Civil War Policy, in which the author warned that “communists are deliberately maneuvering among the American Negroes to create a situation for the outbreak of racial violence”; he believed segregation was “one of God’s natural laws”; he called Martin Luther King, Jr. a communist-educated traitor and an “Uncle Tom for special interests.” Despite the patronizing attitudes that Hargis held against African Americans, he publicly asserted he was not a racist. It wasn’t until Hargis joined forces with former Major General Edwin Walker, however, that racial bigotry became a common characteristic of the religious right.

Operation Midnight Ride: Too Important to be Left to the Generals

Shortly after his resignation from the military, Edwin Walker began forging a friendship with fellow John Birch Society member Billy James Hargis. They agreed to go on a speaking tour of the U.S. together; Hargis would sermonize on the perils of communism at the national level and Walker would expound on the international threat. Walker parlayed these early lectures into political gain. He soon decided to run for governor of Texas and enjoyed the support of Dallas oilman H.L. Hunt. Walker ran under the Southern Democratic (Dixiecrat) ticket, though, and ended up in last place in the Democratic primary of February 1962.

Later that year, in September, Walker caught wind that the federal government planned to force the integration of an African American man, James Meredith, into the University of Mississippi. This was Walker’s chance to retaliate against the government that had forced him to integrate Little Rock back in 1957. Walker took to the airwaves to instigate an insurrection against governmental control.

“I call for a national protest against the conspiracy from within,” Walker declared. “Rally to the cause of freedom in righteous indignation, violent vocal protest, and bitter silence under the flag of Mississippi at the use of Federal troops.”

The next day, September 30, 1962, riots broke out on the university campus, resulting in hundreds being injured and two dead. Six federal marshals had been shot. Walker was immediately arrested and charged with sedition and insurrection against the United States.

Behind the closed doors of the FBI, however, government officials worried about Walker’s mental health. Informants whispered that he appeared irrational during his public talks. The rumors were enough to compel U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to order Walker placed under a 90-day psychiatric evaluation at a forensic center in Springfield, Missouri. Both the American Civil Liberties Union and prominent psychiatrist Thomas Szasz protested the hospitalization. Walker’s attorney in Oklahoma City, Clyde Watts, fought the order of detention and was able to get Walker freed after only five days.

The detention radicalized Walker even further, but by siding with the racists during the Ole Miss riot, he began to cause concern amongst his allies.

“Walker has also been listening to advice from another source and refusing to pay attention to those who have tried to caution him,” wrote Robert Welch, founder of the John Birch Society, adding that Walker could cause “very serious embarrassment to conservatives and the conservative cause in general.”

In November of 1962, Walker stood before a grand jury regarding his role in the Ole Miss riot. His mental health was called into question and his role in the riot scrutinized, yet one of the most important black witnesses, Reverend Duncan Grey, Jr., was never called to testify. The all-white Mississippi grand jury chose not to indict Walker.

Energized by the perceived escape from governmental injustice, Walker teamed up once again with Billy James Hargis. This time, they planned a 12-week 29-city speaking tour starting in Memphis, Tennessee, in late February of 1963. They called their series “Operation Midnight Ride,” and planned to use the talks to create a larger support base. At this point, Hargis’ Christian Crusade had grown to a monthly budget of $75,000—but that money wasn’t necessarily representative of a large audience. Hargis told the New York Times that most of his funding came from oil companies. [12]

While Hargis and Walker were trying to push the general population to the right, they were also galvanizing the extreme fringes of conservatism with their neo-confederate message. According to Walker’s FBI files, the Ku Klux Klan sponsored Operation Midnight Ride in both South Carolina and Arkansas. [13] Throughout America, Hargis and Walker preached against the evils of communism and invited popular right-wing speakers like Benjamin Gitlow, former Army chief of intelligence General Charles Willoughby, and Congressman John Rousselot to join them. The FBI reported that in Washington, D.C., there were about 100 attendees of Operation Midnight Ride and all of them were white. [14] While many inflammatory statements were made at the meetings, the FBI seemed most alarmed by Walker’s rhetoric. In their files, the FBI deemed Walker a presidential threat probably due to Walker’s proclivity to charge presidents as communist leaders and deny them allegiance; there may have been more serious reasons. [15]

More than four thousand people attended the last stop of Operation Midnight Ride in Los Angeles in early April of 1963. [16] Members of the John Birch Society, which had taken over the Young Republicans organization, welcomed the speakers. They presented Walker with a plaque calling him the “greatest living American,” and they listened patiently while Hargis delivered an almost two-hour long talk. The entire operation was a smashing success, or in the recent words of conservative talk show host Bill O’Reilly, “a Paul Revere-like barnstorming tour.”

As Hargis and Walker fomented fears of communism, they could not have anticipated their agitation of one particularly troubled man in Dallas. Lee Harvey Oswald, a former Marine, had recently purchased a 6.5mm Mannlicher Carcano Model 91/38 rifle by mail order. Oswald had been following Walkerclosely enough to formulate an opinion that Walker was a fascist. He had also cased Walker’s Dallas residence at 4011 East Turtle Creek Boulevard and took photos of the house. According to the FBI’s questioning of Oswald’s wife Marina, Oswald took a bus to Walker’s house on April 10, 1963, just days after the first leg of Operation Midnight Ride ended. Hidden in bushes about a hundred feet away, Oswald waited until the moment was right and fired a shot through Walker’s window, barely missing his head. Walker glanced around, thinking at first that a firecracker had been tossed into the room. Oswald claimed to Marina that he fled the scene on foot and took a bus home, but other records suggest that he may have acted with two other accomplices. [17] [18]

“Nothing in my 50 year career of standing up for Christ and fighting Satanic communism equals the success of that undertaking,” Hargis would later reminisce about the tour.

With Operation Midnight Ride behind them, Walker and Hargis turned their aspirations to the national political races, making it clear that their choice for president was the libertarian senator Barry Goldwater. In August of 1963, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his momentous “I Have a Dream” speech in Washington, D.C.; its hopeful message of peace and unity was in direct opposition to Walker and Hargis’ aggressive calls for civil uprising. Two months later, in October of 1963, Walker attended a conference in Dallas in which he once again bashed President Kennedy and his policies. He was probably unaware that Lee Harvey Oswald was in the audience listening.

Hargis and Walker reunited for another tour of Operation Midnight Ride, this time throughout Texas during the month of November. On November 17th in Dallas, they were joined by Alabama’s segregationist governor, George Wallace, who opposed Kennedy’s plan to run on a Democratic ticket. It was well known to many that Kennedy would soon be in Texas campaigning for the ’64 election.

“There were concerns among people close to Kennedy about his traveling to Dallas,” says historian Robert Dallek. “Because the city had a reputation for being the bastion of the right wing.”

With the bulk of their energies devoted to vitriolic political speeches and publications, both Hargis and Walker fostered an environment where an assassination could occur.

According to Warren Commission reports, Walker was involved in two controversial printings criticizing Kennedy in November of 1963: an advertisement in Dallas Morning News which stated “Welcome Mr. Kennedy” that accused Kennedy of communist sympathies, and “Wanted for Treason,” a handbill that mimicked FBI wanted posters, with front and profile views of Kennedy. Prior to Kennedy’s arrival in Dallas, Walker made the extravagant gesture of flying three flags upside down in front of his house—the international distress signal.

On November 22, 1963, Kennedy was assassinated at 12:30 p.m. [19]Following ten months of investigation, the Warren Commission concluded that Lee Harvey Oswald, acting alone, shot and killed the president. [20]

“Our hearts, as a Christian people, go out to Mrs. Kennedy and her family, as well as to our new president,” Hargis wrote in December of ‘63. “We stand as one man in disbelief that an enemy of our country could be so brazen in our midst.”

Soon after Kennedy’s assassination, Walker flew his flags right side up and at full mast, in defiance of the traditional half-mast position declared during times of national mourning.

Before All the Facts Are In

Throughout the ‘60s, Hargis’ Christian Crusade enjoyed tremendous success, but not without its challenges. The Internal Revenue Service began its battle with Hargis, alleging that the Christian Crusade overstepped the political boundaries of a religious organization. [21] Undeterred, Hargis continued building his empire and publishing tracts, pamphlets and books. He started a foundation for missionaries, and created an anti-abortion organization.

In 1971, Hargis founded American Christian College and changed the mission of The Christian Crusade. No longer would it focus on external problems (anti-communism) but instead “internal moral problems” like drug use, the sexual revolution, and “Satan worship.” He remained incredibly productive and financially successful, and rightfully referred to Tulsa as the Christian “Fundamentalist Capital of the World.”

That world met its Doomsday when, in 1974, Time magazine accused Hargis of sexual misconduct with several of his Bible college students, both female and male. The incident forced Hargis’ resignation from the college.

“It was a really challenging time for our family,” recalls Hargis’ daughter, Becky Frank, who now serves as the president of the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce.“I think Mom and Dad did a really beautiful job working through all of those things.” As an owner of a Tulsa-based public relations firm, Frank helps religious organizations manage crises through their faith-based consulting services. Among the firm’s more conservative clients are Oral Roberts University, which faced a major financial scandal, and Victory Christian Center, a Tulsa megachurch currently embroiled in a child rape investigation.

“Several of our team members have first-hand experience in working for faith-based universities and organizations, both inside and as a consultant,” boasts the firm’s website. “The team understands the culture and knows the challenges. Not only do they understand where you are—chances are, they’ve been in your shoes.”

Not long after Hargis’ scandal, General Walker fondled an undercover policeman in the restroom of a public park in Dallas and was arrested for public lewdness. Twice. Walker pleaded no contest and paid a fine; Hargis denied the allegations of sexual misconduct yet told a reporter that he was “guilty of a sin but not the sin I was accused of.” [22]

The American Christian College closed its doors in 1977.

The allegations of Walker’s attempted assassination by Oswald remains one of the most fascinating and obfuscated subplots related to the Kennedy assassination. That connection haunted Walker his entire life; his personal papers are replete with Freedom of Information Act requests that petition for the release of government files surrounding the assassination. Walker died of lung cancer on Halloween day, 1993.

“My heart is sad today. I lost one of my best friends Sunday,” Hargis said in a televised tribute, adding “I never had a greater friend than General Edwin A. Walker; I never knew a greater patriot.”

The many political and religious figures who associated with Hargis continue to shape America’s conservative landscape today. Hargis’ mail-order apprentice Richard Viguerie helped establish the Young Americans for Freedom, a conservative activism program for youth. Viguerie later became a pioneer of direct mail politics and one of the GOP’s most successful fundraisers. [23] Conservative talk radio hosts like Rush Limbaugh, Bill O’Reilly, Sean Hannity, and Glenn Beckall borrow—knowingly or not— from Hargis’ pioneering speaking style and old South ideology. Former American Christian College president David Noebel, a fellow “Bircher,” authored numerous books that argued against perceived evils such as rock music, homosexuality, and most recently, communism.

Hargis continued his ministry until his death from complications related to Alzheimer’s disease in 2004. His son, Billy James Hargis II, continues The Christian Crusade online, though publications are somewhat irregular.

Note: Research for this article was conducted with the help of Special Collections at the University of Arkansas Libraries in Fayetteville, the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History, University of Texas at Austin, and the Eagle Forum Archives and Library in St. Louis, Missouri. Special thanks to independent researchers Ernie Lazar and Paul Trejo for their assistance.

Footnotes

1. In 1917, the National Council of Defense organized a national propaganda system in each state. In Oklahoma, the councils functioned primarily to identify anyone who did not approve of America and its presence in the war. The Tulsa County Council of Defense was organized through the Tulsa Chamber of Commerce and was a particularly enthusiastic participant in extralegal vigilante activities.

2. Following the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921, the Ku Klux Klan in Tulsa owned a large temple or “klavern” called Beno Hall: “The Tulsa Benevolent Association [KKK] sold the storied building to the Temple Baptist Church in 1930. During the Depression, the building housed a speak-easy, then a skating rink, then a lumberyard, and finally a dance hall before radio evangelist Steve Pringle turned it into the Evangelistic Temple of the First Pentecostal Church. In his first revival meeting, Pringle introduced a little-known Enid preacher by the name of Oral Roberts, who worked his animated, faith-healing magic on the bare lot next door. Roberts impressed in the tent atmosphere and preached with his cohort inside the vast auditorium.” Excerpted from “Beno Hall: Tulsa’s Den of Terror,” by Steve Gerkin, published in This Land Volume 2, Issue 11, September 15, 2011.

3.The International Council of Christian Churches was founded by Carl McIntire, a fundamentalist radio broadcaster from Durant, Oklahoma.

4. Hargis claimed that he had ghostwritten a number of speeches for Senator McCarthy.

5. The John Birch Society is a conservative political advocacy organization. One of its founders was Fred Koch, who also founded Koch Industries. Koch advised JBS president Robert Welch on numerous issues. He believed many U.S. companies had been infiltrated by communism, as evidenced by the presence of labor unions. Today, two of Koch’s sons, David and Charles, are one of the largest contributors to conservative political campaigns and causes in America.

6. Hargis would later claim that a plot to smear Walker was hatched by the Kremlin because they feared what might happen if Walker gained more power in the military.

7. The Texas Minutemen were an extreme right-wing paramilitary group that supplied weapons to Cuban exile groups in Dallas and New Orleans. Walker has been often cited as its leader, though he denied being involved before the Warren Commission.

8. General Jack Ripper in the film Dr. Strangelove cites the fluoridation of America’s water supply was evidence that communist had infiltrated the highest powers of government and were trying to destroy America’s “precious bodily fluids.” The character Ripper was based on General Curtis LeMay and Major General Edwin Walker. On November 22, 1963, Dr. Strangelove was set for its first screening. When news of PresidentKennedy’s assassination reached Kubrick in California, he cancelled the screenings and rescheduled the screenings for the following January. While waiting for the shock of the assassination to pass, Kubrick edited out a reference to “Dallas” in the film and changed it to “Vegas.”

The John Birch Society opposed the fluoridation of water, arguing that it was part of a communist plot to poison Americans. By 1960, about 50 million Americans were drinking fluoridated water, resulting in an estimate reduction of tooth cavities by 40%. Today, about 66% of of the U.S. population drinks received fluoridated water through their public water system. Hargis kept a file on fluoridation.

9. Since Walker resigned instead of retired from the military, he relinquished his pension and military benefits. In 1982, President Ronald Reagan returned Walker to an active role status in the Army, allowing Walker to enjoy full benefits.

10. Hendershot, Heather. What’s Fair on the Air: Cold War Right Wing Broadcasting and the Public Interest. Pg 183.

11. Marion Romney, a cousin to the father of politician Mitt Romney, was supposed to succeed BENSON as president of the Church of Latter Day Saints but his health prevented him from doing so.

12. It should be noted that at the Washington, D.C. stop for Operation Midnight Ride, Hargis stated that he had never received a penny from Texas oilman H.L. Hunt.

13. Walker’s ties to the Klan ran deep. In 1964, he was the main speaker for Americans for the Preservation of the White Race in Brookhaven, Mississippi. A year later, in 1965, the Imperial Wizard of the United Klans of America offered Walker the position of Grand Dragon of the UKA of Texas. Walker turned the offer down.

14. According to Hargis’ recollection 30 years later, 2,000 people attended the first evening of Operation Midnight Ride in Washington, D.C. He also stated that he and Walker had toured 100 cities and that their rallies were attended by over a hundred thousand people.

15. The FBI kept Walker under regular surveillance following his resignation from the Army. Please refer to footnote 17 & 20 for additional motives the FBI had to monitor Walker’s activities.

16. One week prior to the finale of Operation Midnight Ride in Los Angeles, a bombing destroyed the offices of the American Association for the United Nations in nearby Encino. The executive director blamed the bombing on the incitement of UN fearmongering by extremists; it was no secret that Walker and Hargis vehemently opposed the UN.

17. Walker’s conflicting testimonies, actions, and activities surrounding the Kennedy assassination have created a number of challenges for researchers and historians. Here’s what we do know: according to FBI records, Walker was informed shortly after his assassination attempt that the shooter was Lee Harvey Oswald, and that Oswald was likely not alone—yet before the Warren Commission, Walker denied knowing any of this prior to the Kennedy assassination. Not long after the attempt on his life, Walker hired two detectives from Oklahoma City to pose as men seeking to kill Walker. The detectives attempted to entrap a man named William Duff, a former live-in friend of Walker’s (there were several). Duff accepted the hit, but then turned around and called the FBI. Duff also passed a polygraph test denying that he tried to shoot Walker, and the case against Duff was dropped.

18. Hargis believed that Fidel Castro ordered Lee Harvey Oswald to shoot Walker.

19. At the exact time of Kennedy’s assassination, both Hargis and Walker were passengers in different airplanes. Hargis was en route from Los Angeles to San Diego; Walker was between New Orleans and Shreveport.

20. In 1962, a former Castro sympathizer turned CIA informant named Harry Dean infiltrated the John Birch Society. He claimed that society members Walker and John Rousselot hired two gunmen to kill John F. Kennedy, and that they planned to frame Lee Harvey Oswald. Dean, however, could not produce any evidence to substantiate his claim.

21. The tenth circuit court of appeals eventually upheld a ruling in 1972 that caused Hargis’ Christian Crusade to lose its tax exempt status. Other churches have since lost their tax exempt status for participating in political campaigns.

22. During much of the Red Scare, homosexuality was often conflated with communism. David Johnson, author of The Lavender Scare: The Cold War Persecutions of Gays and Lesbians in the Federal Government, says “The politicians behind the Lavender Scare asserted that homosexuals were susceptible to blackmail by enemy agents and so could be coerced into revealing government secrets. In other words, the official rationale wasn’t that homosexuals were communists but that they could be used by communists.”

23. In 2004, Viguerie commented to the New York Times that Karl Rove was one of his direct mail marketing competitors in Austin. Rove employed the same strategies that Viguerie pioneered in order to help mobilize the religious right in George W. Bush’s favor.

Originally published in This Land, Vol. 3, Issue 21. Nov. 1, 2012.