1964 was a fertile year for Joe Brainard. After a brief retreat from the pressures of establishing himself in New York (aggravated by the fear that his work had begun to go stale), the young Tulsan was back in the Big Apple—re-energized and forging lifelong relationships with new friends, lovers, and fellow artists. That year, he saw his work chosen for a group exhibition, with his first New York solo gallery show and a book collaboration only a few months away. And when he wasn’t pushing the envelope in the fine arts, he was devoting hours to blazing a trail in, of all things, the world of cartooning and comics.

People looked at comics differently then. Beyond the work of a handful of big-gun political cartoonists and superstar magazine artists like Charles Addams, the medium was almost universally seen as a featherweight enterprise. Newspaper strips were ephemeral amusements, delivery systems for jokes and serialized snippets of soap opera that appeared alongside daily horoscopes and simple word jumbles. And as negligible as the likes of Mr. Abernathy and Mary Worth were, they were the epitome of gravitas when compared to comic books. To anyone who’d moved beyond grade school, those 12-cent pamphlets were popularly considered to be nothing but childish trash.

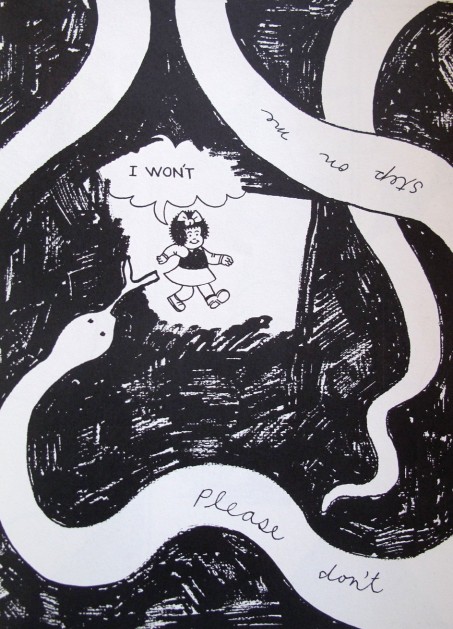

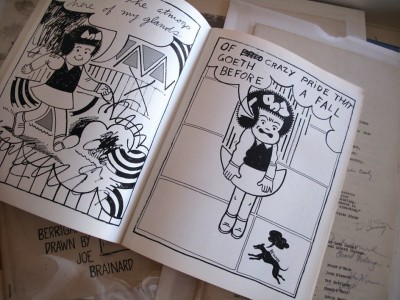

None of that mattered to Brainard, who saw untapped potency in the medium’s combination of words and pictures. Working with poets of a kindred spirit like John Ashbery, Kenward Elmslie, Frank O’Hara, and fellow Tulsan Ron Padgett, Brainard created the first volume of C Comics, a mimeographed anthology of short works that stood the conventional notion of cartooning on its ear by asking a question that had rarely, perhaps never, been asked: If comics are suitable for narrative, then why not poetry?

The pop art movement, with its appropriation of imagery from advertising and comics, was well established by this time, and Brainard was captivated by the achievement of practitioners like Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. But even before he’d encountered their work, the impulse to transmute comics into gold was already there. He’d devoured comic books in his childhood and teen years, and as a matter of course had already made occasional use of cartoon icons like Nancy and Dick Tracy in his work. When he was recruited by another Tulsa refugee, Ted Berrigan, to contribute to the mimeoed magazine C: A Journal of Poetry , comics-derived images eventually became part of the package. The seventh issue, for instance, featured a cover cobbled together from repurposed art and logos in conventional pop art style—but that approach quickly evolved toward a more personal statement with the very next issue. That one featured a full-blown comics page for a cover, the 24-panel “Love Pictures” with words by Berrigan and art by Brainard that was not repurposed, but original, and infinitely more human.

That humanity was what separated Brainard’s work from much of the pop art product. Works like Lichtenstein’s celebrated comic book pastiches were cold and condescending comments on a less fortunate art form, a schoolyard bully intent on taking away the runt’s lunch money and pantsing it on the playground. Brainard’s comics, by contrast, embraced the form and achieved something considerably more magical than mere irony.

By the time his C: Journal covers saw print, Brainard had been working on comics-style projects for at least a year, enlisting as his collaborators some of the brightest lights among the New York School poets. Some of those writers may have been attracted initially by the lure of pop art (in those days, too, it was hip to be square), and not all of them were enchanted with the idea of working in a “childish” medium. But, in most cases, the potential of the form, combined with Brainard’s talent and personal charm, won them over, and the results were frequently impressive.

The working method on C Comics #1 fluctuated from collaboration to collaboration—sometimes the poets would add their words after Brainard had completed his art, sometimes vice versa. In either case, the tension between the two elements produced remarkably varied works. Brainard’s interpretation of his own poem “People of the World: Relax!” communicated its simple life-embracing message through a series of captioned panels that evoked the art in old high school yearbooks. The approach to “Red Rydler and Dog” (created with Frank O’Hara), on the other hand, appropriated the narrative machinery of conventional pulp comics to present a character study of a gay cowpoke and his missing pooch.

Many of the “Red Rydler” visuals were redrawn images from the Red Ryder newspaper strip—many of Brainard’s comics were, in fact, repurposed from other sources—but the similarity between his comics and the commentary of pop art was purely superficial. Fascinated by collage and assemblage, Brainard was born to reinterpret found objects and felt that he did his best work if he had an example before him to jump-start his process. Much of his comics work involved transforming the basic ideas found in old postcards or photos into new images shot through with his own warmth and aesthetics. (As noted by Ron Padgett in his biography Joe: A Memoir of Joe Brainard, “Rydler” was also a demonstration of the freedom he’d learned through earlier collaborations with Ted Berrigan. When he made a hash of drawing the face of Rydler’s dog, Brainard simply scribbled over the mistake and proceeded to draw the dog with the same mass of black squiggles for the rest of the strip—a touch that was then incorporated into the text.)

C Comics was successful enough in its creators’ minds to merit a second issue the following year, this time in an offset format. A third issue was contemplated in 1969 but never completed; however, it wasn’t the end of Brainard’s commitment to the comics form. During the mid-‘60s he published a number of cartoons in the East Village Other, and contributed a striking set of pages to Cherry, a collaboration with Ron Padgett that reinterpreted European fumetti into a series of images that allied the stark line work of woodcuts with the heavily inked chiaroscuro of noir.

He turned out two more long-form collaborations the following decade. The Class of ‘47 (1973), with Robert Creeley, illuminated the blowhard text of an Ivy League booster by playing it against confidently rendered views of cartoon characters and advertising images. Perhaps his most accomplished cartooning is on display in the 1971 “Sufferin’ Succotash” (again with Padgett), which was published in a back-to-back Ace Double format with “Kiss My Ass,” a collaboration with Michael Brownstein.

Given the breadth of Brainard’s accomplishment during his career, it’s understandable that his experiments with comics have received comparatively little notice—but much of that work is far from minor, and deserves to see the light of day again. In the years since his death, a small but vital “arts comic” market has arisen, some of its creators undoubtedly ignorant of the fine artist who blazed the trail for them over 40 years ago. But Joe Brainard did it first, and he remains the guy who did it as well as anyone could. With any justice, the day may come when we can not only see his work in museums, but also, once again, in the funny papers.

Editor’s note: The “C” imprint stood for “Censored” not “Collaboration”.