“You can leave your contraband at the door,” the woman tells me.

I’ve filled out and signed several forms and waited while my name, driver’s license number, and other personal information were filed away on a computer system. I’ve agreed that my camera, brought for personal reference, will not be used with a flash and will not at any time rest on a tripod. I’ve signed my life away in order to spend a single hour with a rare book, and now I’m emptying my pockets. I’m at the University of Tulsa, in the Special Collections department of McFarlin Library, and I’m here to view one of their most recent acquisitions.

I dig into my jeans and comb through change, keys, cigarettes, lighter, cell phone, loose ibuprofen tablets, a black Pilot ball-point. The woman—a friendly, if harried, librarian named Alison—motions to the table next to me. I toss the contraband onto the surface and follow her past the entrance.

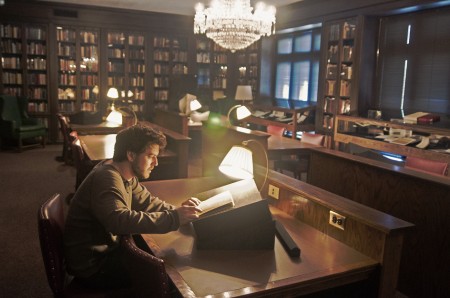

We emerge into a magnificent reading room. The ceiling is high with an opulent crystal chandelier hanging from the center of it, and each wall is completely occupied by glass-encased floor-to-ceiling bookshelves filled with collections from greats like Robert Frost and Walt Whitman, plus the fourth largest James Joyce library in the world. Six very large desks lie before me in perfect symmetry. Each is identically furnished with a small lamp and a black, monolithic book rest. The light is perfectly dim, creating a glowing, otherworldly warmth.

She tells me to sit where I like. I slip into a seat at the nearest desk and wait. Earlier, I was told that a staff member would remain in the reading room to monitor my activity with the book, and, sure enough, an awkward student receptionist has taken a seat at the head of the room. I will not be alone with the White Dove Review for a moment.

“It’s kind of hard to express what Special Collections does,” department head Marc Carlson explained to me a few days earlier. A scholarly, bookish fellow, Carlson has run Special Collections for six years now, but even for him, the mystique of his department has not worn thin. As he struggles for the words to best explain the essence of that department, I realize that Carlson is really a gatekeeper to the significant puzzle pieces (historical artifacts, manuscripts, parchments) that compose the lost history of Tulsa—the parts that seem to be intentionally hidden by museums like Philbrook and Gilcrease.

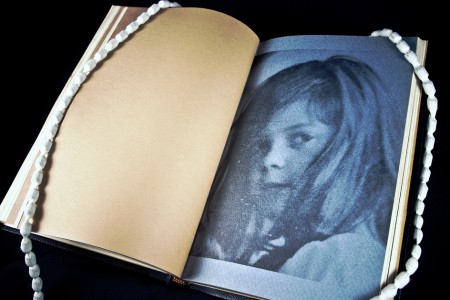

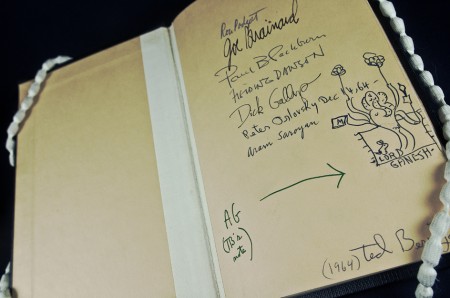

Now, sitting in the reading room, I’m finally handed the aging black-bound text. The covers are unmarked; the spine reads “White Dove Review 1-5” in gold-embossed letters. The ripened paper is a deep yellow bordering on brown, but the ink seems fresh and vibrant, as if put to paper just moments before I arrived. I cautiously pull open the cover to the first page and my eyes widen: it contains wild, loose signatures and illustrations. The markings come from many of America’s most renowned poets and painters.

A scrappy little literary journal published in 1959 and 1960, the White Dove Review contains in its brittle pages one of our city’s best-kept secrets: a clear, concrete link between Tulsa and the Beat Movement, America’s most iconic literary scene of the twentieth century. It’s also a telling portrait of Oklahoma’s most important artists as young men, a small group who would go on to help define the New York School of the 1960s. The entire original five-issue publication is bound in this one guarded book.

“My understanding is this was a publication put out by, essentially at that point, a bunch of kids,” Carlson told me. It’s hard to believe that the ritualistic security protocol I’ve just gone through is for something created by a group of Central High students out of a house located just a few blocks from here.

Joshua Kline examines the White Dove Review at the Special Collections Dept. at McFarlin Library. Photo by Michael Cooper

THE OUTSIDERS OF CENTRAL HIGH SCHOOL

In 1959, Ron Padgett was a working-class teen, a misfit whose father was a bootlegger. He was a sensitive boy, intelligent and ambitious, an aspiring poet who was routinely drunk on Kerouac, Ginsberg, Camus, and Rimbaud.

“Basically, I was an outsider on his way to becoming something of a bohemian,” Padgett said of those early days, in an e-mail interview. “Fated to meet other outsiders, whether in Tulsa or New York.”

While working at the Lewis Meyer bookstore on 37th and Peoria that year, Padgett had an idea. Taken with the work of the era’s literary giants and New York-based “little mags” like the Evergreen Review, Padgett, barely 17 and still a junior at Central, decided that he would start his own avant-garde lit journal. He and his best friend Dick Gallup would be co-editors.

Gallup, who lived across the street from Padgett, had moved to Tulsa from Massachusetts in grade school.

“When I first met Dick (he was about 10, I was 9),” Padgett remembered, “he seemed rather exotic to me because he was from western Massachusetts and he spoke with that accent.” The two meshed well. As children, they played basketball and baseball, watched television together, and frequented local movie theaters like the Orpheum and the Majestic.

In junior high, the budding thinkers gravitated to more intellectual pursuits and pastimes, especially the quiet, observant Gallup.

“Dick was always coming up with rather abstruse and mysterious ideas about things such as anti-matter,” Padgett recalled. “But inside he had a very good adolescent sense of humor, and if you knew him, you could sense that he was growing into his own person.”

By high school, they were hanging out at Lewis Meyer Bookstore so often that Meyer offered Padgett a job. In addition to introducing the boys to a slew of edgy, contemporary authors, the store owner gave Padgett his first glimpse of what would lay the foundation for his concept: those avant-garde journals like Evergreen, Yugen, and Semina that contained short-form work from the same Beat and Black Mountain writers he was then devouring.

With two enthusiastic editors, the ambitious concept was becoming a reality. The next step was to recruit art editors. Padgett was fascinated by the work of a classmate he didn’t know named Joe Brainard. Instead of approaching him directly, Padgett sent the artist a Christmas card praising his talent. Soon after, he approached Brainard at school and revealed himself as the sender, and then pitched the idea of Brainard as the journal’s art editor. Brainard agreed.

Padgett remembers the artist as being “shy, sweet, passive, soft-spoken—the epitome of a ‘nice’ kid,” but also described Brainard’s growth in high school as becoming increasingly aware of himself (Brainard was gay– no easy burden for a teenager in ‘50s Tulsa) and “determined to take control of his life.”

They invited fellow aesthete Michael Marsh, a classical pianist who introduced the growing team to the work of Debussy and Capote, to be Brainard’s co-editor.

They called their magazine the White Dove Review, an homage to Evergreen, which featured on the cover of its sixth issue a striking black and white photograph of a young Asian woman holding a white dove. To fund its publication, they enlisted the help of Padgett’s mother, who donated $20 of the first issue’s $90 production cost. To typeset the journal, they borrowed the state-of-the-art IBM Presidential from their good friend and fellow classmate George Kaiser, who, Padgett said, “provided moral support for the magazine.” Even then, the future billionaire philanthropist was indulging his altruistic tendencies, playing an arts patron through the simple loaning of a typewriter.

Though they didn’t run in the same social circles, Padgett and Kaiser got to know each other through many shared classes.

“I liked him because he was smart and he had a good sense of humor,” Padgett said. “We often had lunch together at Nelson’s Buffeteria, or we’d hop in his car and speed out to Pennington’s, then rush back to class, eating on the way.”

They had their own poems, their own artwork, their own typewriter, and their own start-up funds. But then the White Dove editorial board took a bold step. Padgett and Gallup decided to fill the White Dove’s pages with the work they solicited from their heroes.

“Dick and I made a list of the living writers we were excited by,” Padgett explained. “Kerouac, Ginsberg, e.e. cummings, Malcolm Cowley, Paul Blackburn, etc. Then we wrote to them, care of their publishers, asking—begging, really—them for material. Our letter was rather immature, but in it we did confess to being in high school.”

According to Padgett, “a surprising number of writers responded” to the solicitations, and with the submitted work he and Gallup were able to choose what best fit their vision. The crown jewel of Issue One is Jack Kerouac’s “The Thrashing Doves,” a poem submitted by the Beat godfather as a knowing salute to the Review’s avian imagery:

The thrashing doves in the dark, white fear,

my eyes reflect that liquidly

and I no understand Buddha-fear?

awakener’s fear? So I give warnings

‘bout midnight round about midnight

And tell all the children the little otay

story of magic, multiple madness, maya

otay, magic trees- sitters and little girl

bitters, and littlest lil brothers

in crib made of clay (blue in the moon).

For the doves.

THE EDITORS ARE NOT HIPSTERS

Sitting in the grand reading room, I stare at the signatures on that first page: Padgett, Brainard, Gallup, Blackburn, Ted Berrigan, Fielding Dawson, among others. There’s a handwritten date next to Peter Orlovsky’s (the famous poet who was Allen Ginsberg’s lifelong romantic partner) signature: December 14th, 1964. The autographs were likely collected in New York after the White Dove boys had already fled Tulsa. There’s a goofily grotesque cartoon drawing of what looks like a half-elephant, half-man creature standing on a magic carpet. Resting under the drawing is the name “Lord Ganesh,” and next to the drawing are the initials “AG” (later in the book I find Ginsberg’s signature under his piece “My Sad Self”). Already, the camaraderie of the New York School and its inseparable connection to the White Dove Review is crystal clear.

Signatures collected for White Dove Review, including one from Allen Ginsberg. Photo by Michael Cooper.

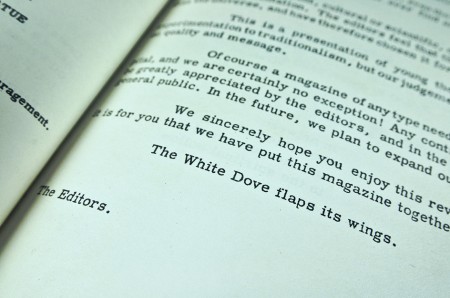

I move on to the editors’ introduction:

There has been sufficient criticism of materialistic, uncultured modern American society. The intention of this mag is not to add to this stockpile of criticism, but rather to present literature and art in a constructive light. Admittedly, The White Dove Review is a quiet complaint against the gaudy ideals of our society. Culture, along with some short-lived memories, is all a civilisation leaves behind it. We hope that the Schleimanns of the year 4000 do not find only beer cans and long cars in their excavations. (sic)

He adds in the next paragraph:

The editors are not hipsters, even tho they acknowledge certain beat ideas. But no one will ever find any ‘organization’ dogma within these covers.(sic)

Romanticized characterizations of the lusty city life pepper the contents of the White Dove—counterculture ruminations on jazz and drugs and sex and just barely scraping by—the kinds of images rampant in the seminal Beat offerings (Howl, On the Road) that Padgett and Gallup idolized, but were seldom, if ever, used to describe life in Tulsa.

Nevertheless, writings in the White Dove toggled freely between the earthy, Midwestern concerns found in poems like Marsha Meredith’s “Streetlight in the Snow:”

a candy candle

preening in the downy

dreamy

snowy

night

and the freewheeling chaos of the Beat contributors and big city natives like Carl Larsen (who, in his poem “Crap and Cauliflower”, paints a graphic portrait of loose sexuality culminating in rape and disillusionment) and Paul Blackburn’s “Redhead:”

you are the poor

slick-minded Madison

ave. man’s

idea of a mistress

no serious thing at all.

These peculiar juxtapositions of middle-American and coastal big-city musings cultivated a spiritual connection between Tulsa and New York City, a connection that would prove prescient for its creators in the years to follow.

THE BEATS OF TULSA

Over the course of the White Dove’s five-issue run between ’59 and ’60, Padgett and company continued to showcase a distinguished mixture of lauded artists from New York and abroad (Ginsberg, Blackburn, Dawson, Major, LeRoi Jones, Simon Perchik, Ron Loewinsohn) along with a select core group of homegrown writers, painters, and poets, including John Kennedy, Bob Bartholic, Dave Bearden, Paul England, and Marsha Meredith.

Another Tulsa poet on board with the White Dove was Ted Berrigan. A patron of Lewis Meyer, Berrigan submitted work to the journal through the slot of an old cigar box that Padgett normally used to collect payment for the paper.

The coalescing, creative partnership between the three editors (Padgett, Gallup, Brainard) and Berrigan was particularly important during this period. Berrigan, whose work would eventually be considered “a fact of modern poetry” by Frank O’Hara, became a driving force behind the publication of the Review. At 25, the worldly TU student acted as an elder statesman and mentor to the fledgling editors behind the journal, and Padgett in particular was enamored with what he described during a speech at TU as Berrigan’s “irresistibly romantic” and “glamorously outsiderish” persona.

“Even though he had not yet become ‘Ted Berrigan,’ he was already very different from Tulsans, more expansive and with a larger sense of humor,” Padgett said.

The White Dove Review only ran for a year, but in that time the four young men became entrenched in Tulsa’s art scene.

“There really weren’t very many outsider poets and artists in Tulsa in the 1950s, which meant that we tended to huddle together, despite our differences,” Padgett said. “The relationships tended to be intense, sometimes competitive.”

They mixed with the student cutters of TU’s Nimrod (of which Berrigan was an editor), hung out at coffeehouses, all-night diners, and the jazz club Rubiot (where a trembling Padgett gave his first public reading) and congregated at the house of John and Betty Kennedy on 6th and Peoria. The Kennedys were 30-something artists whose always-open home acted as an important point of convergence for a handful of Tulsa bohemians. They held frequent parties for their friends and transformed a wing of their home into a multi-purpose artist exhibition and workspace dubbed Gallery 644.

The cover of Issue 3 is a portrait of Betty Kennedy’s and Bob Bartholic’s daughter Chrissie (by the girl’s stepfather, John Kennedy), and the issue also features a moving piece by Padgett titled “Poem for Chrissie:”

for now

stay warm and silent

and ten.

By the time the younger of the White Dove graduated from high school, a mass exodus was underway. The Tulsa beatniks ran to New York, and Padgett, Gallup, Brainard, and Berrigan followed closely behind. When they arrived in the Big Apple, they seamlessly integrated into the New York School, a loose collective of artists and performers who were radically re-defining the parameters of self-expression. Ultimately, the four White Dove boys carved out a niche of their own within the New York School, becoming known as The Tulsa School of Poets. The origin of this title is the subject of some debate, but it’s generally agreed upon that poet John Ashbery first popularized the term. According to Terrence Diggory’s Encyclopedia of the New York School Poets, the term “Tulsa School” was something of a running joke.

“To call them the ‘soi disant’ (self-proclaimed) Tulsa School,’ as John Ashbery did, was to poke fun at the provinciality of Tulsa, from the perspective of New York,” Diggory writes, “and to turn the tables on Berrigan, who jokingly authorized himself to enroll people in the New York School for a five-dollar fee.”

Joke or not, the “Tulsa School” was a phrase that would forever be attached to the four T-town expatriates. The teenagers who started the White Dove Review eventually found recognition and acclaim in corners of the world spanning New York to Paris.

A PRESENTATION OF YOUNG THOUGHT

An hour has passed. The student receptionist has graduated from awkward to bored, and I feel the onset of a lit hangover. I feel like I’ve been watching a peculiar, literary puppet show: trembling poets in smoky jazz clubs, rough-and-tumble hedonists, drunk writers, introverted painters, young intellectuals and innocents s if Ginsberg’s “best minds” were misplaced in Tulsa before finding their way back to Greenwich Village.

I flip back to the editors’ introduction in Issue One and read again:

This is a presentation of young thought. We favor experimentation to traditionalism, but our judgments will be based on quality and message.

We sincerely hope you enjoy this review because it is for you that we have put it together.

The White Dove flaps its wings.

The Editors.