-

The Pickup

READ THE PICKUPThe Pickup is a new voice in Tulsa media from This Land Press. With stories that speak to what Tulsa is and where it’s going The Pickup sparks dialogue, asks provocative questions, and offers ways to become more connected to Tulsa.

-

Books

SHOP BOOKSFrom anthology collections that represent the most compelling essays from This Land magazine, to selected titles from Oklahoma's most profound thinkers, our book selection is the best of This Land.

-

Apparel & Gifts

SHOP THE COLLECTIONWe envision This Land is a brand that redefines the middle of America. Our selection of apparel, gifts, and accessories is sharp, smart, and always made of the highest-quality materials.

Featured Anthologies

-

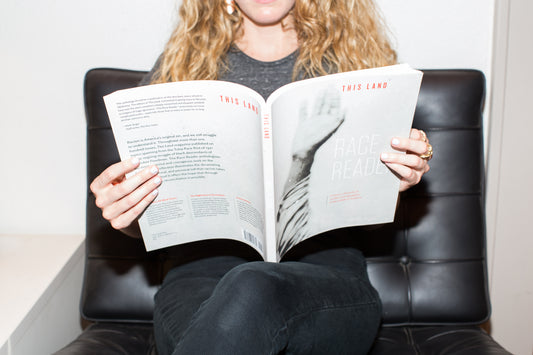

The Race Reader

Regular price $ 30.00Regular priceUnit price / per -

Sold out

Sold out -

Sold out

Sold outReader Bundle Pack

Regular price $ 55.00Regular priceUnit price / per$ 60.00Sale price $ 55.00Sold out -

A Voice Was Sounding Vols. 1&2

Regular price $ 17.99Regular priceUnit price / per

This Is My Beloved Son

As long as there are Christians in Tulsa, Oral Roberts University will loom large in their imagination. In her feature story for This Land, Kiera Feldman examines the implosion of the Roberts family's televangelism empire.